Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

This podcast brought to you by Ring. With Ring cameras, you can check on your pets to catch them in the act. Izzy, drop that. Or just keep them company. Aw, I'll be home soon. Make sure they're okay while you're away. With Ring. Learn more at ring.com slash pets. Hi, it's Phoebe.

We're heading back out on tour this fall, bringing our 10th anniversary show to even more cities. Austin, Tucson, Boulder, Portland, Oregon, Detroit, Madison, Northampton, and Atlanta, we're coming your way. Come and hear seven brand new stories told live on stage by me and Criminal co-creator Lauren Spohr. We think it's the best live show we've ever done. Tickets are on sale now at thisiscriminal.com slash live. See you very soon.

In 1887, a young woman walked into a boarding house in Manhattan to rent a bed for the night. She was dressed in nice clothes, but she had no luggage and not much money. She said her name was Nellie Brown. But when the other women at the boarding house asked her where she had come from and how long she had been in New York, Nellie Brown said she couldn't remember. Some of the other women thought she acted strange, and they became scared of her, so they went to the police.

Nellie Brown was brought before a judge in Manhattan, but still couldn't explain where she'd come from. The judge wasn't sure what to do with her. And then one of the police officers who was present said, send her to the island. Nellie Brown was put on a boat with a few other people. The boat crossed New York's East River, and soon it docked on a small island. A man and a woman grabbed Nellie Brown's arms and led her up the plank. She asked the man where they were. He responded,

Blackwell's Island, an insane place where you'll never get out of. She was put in an ambulance with another four women. The ambulance headed straight for what was called the New York City Lunatic Asylum. The asylum's entrance was a large octagonal building. When they arrived at the octagon and walked up its stone stairs, Nellie Brown turned to the woman next to her and asked, "Are you crazy?" "No," the woman said.

But we will have to be quiet until we find some means of escape. Only women were sent to the asylum on Blackwell's Island. It was relatively easy in those days to get someone committed.

Author Stacey Horn. You had to take them before a judge, and the judge at this time were police justices. The courts were very different than how they are now. And when you're arrested or someone's trying to commit you, you first go to a police court, and you're brought before a police justice, and they just need to get a doctor,

or a priest or an apothecary to say that you are suffering from some sort of mental illness. And you could see how who was being committed was a reflection of the bias at the time. And at the time, New York was very anti-women who wouldn't stay in line. Stacey Horn says that women who didn't fit the norms of society could easily end up in an asylum.

If she was very independent, if she was very difficult, if she fought for independence in any sort of way, they could get her committed. If she was suffering from simple anxiety or depression, they could get her committed. When Nellie Brown arrived at the New York City Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island, she tried to tell the doctors that she did not belong there. She told the doctor, I am not sick, and I do not want to stay here. No one has a right to shut me up in this manner.

The doctor ignored her. She later wrote, "'I began to have a smaller regard for the ability of doctors. I felt sure that no doctor could tell whether people were insane or not. She was taken into a cold room with a bathtub. She refused to undress and get into the bathtub, but, quote, they said if I did not, they would use force and that it would not be very gentle. Then buckets of freezing cold water were poured over her head."

And all the women in the institution would have to go through these same bathtubs over and over and over and over. So in a few hours, depending on the condition of the women who were admitted that day, these things would be like more sludge than water and just filled with feces and vermin. And you take, you know, a vulnerable woman who is suffering from whatever, postpartum depression, although that wouldn't have been diagnosed then, and tell her she has to step into that.

Nellie Brown wrote, Nellie Brown wrote,

Nellie Bly. Nellie Bly was born in 1864 in Pennsylvania. Her father died when she was young and she had to drop out of school to work. And she started writing a newspaper column. Then she moved to New York. She walked into the offices of the New York World, Joseph Pulitzer's paper. She said she wanted to write a story about immigration, but the editor had another idea.

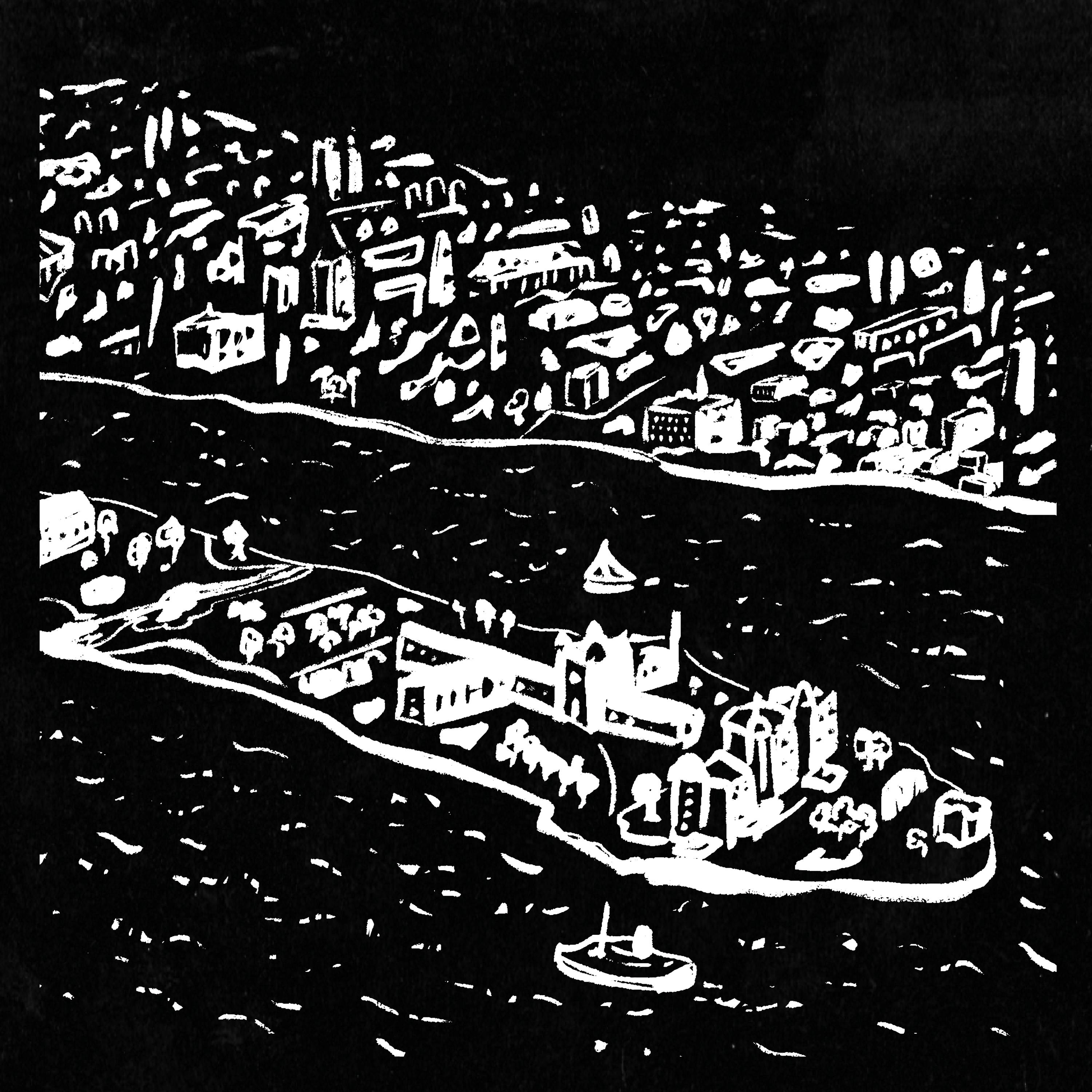

He asked her to get herself committed to the New York City Lunatic Asylum at Blackwell's Island and write about what was going on inside. But once she got to the asylum, she wasn't able to write to anyone on the outside. Nellie Bly wrote, The insane asylum on Blackwell's Island is a human rat trap. It's easy to get in, but impossible to get out. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal. We'll be right back.

Support for Criminal comes from Ritual. I love a morning ritual. We've spent a lot of time at Criminal talking about how everyone starts their days. The Sunday routine column in the New York Times is one of my favorite things on earth. If you're looking to add a multivitamin to your own routine, Ritual's Essential for Women multivitamin won't upset your stomach so you can take it with or without food. And it doesn't smell or taste like a vitamin. It smells like mint.

I've been taking it every day, and it's a lot more pleasant than other vitamins I've tried over the years. Plus, you get nine key nutrients to support your brain, bones, and red blood cells. It's made with high-quality, traceable ingredients. Ritual's Essential for Women 18 Plus is a multivitamin you can actually trust. Get 25% off your first month at ritual.com slash criminal.

Start Ritual or add Essential for Women 18 Plus to your subscription today. That's ritual.com slash criminal for 25% off. This is pretty convenient to have this bus that goes around the island. I agree. It's very convenient. Earlier this year, we were on a bus going around Roosevelt Island. Roosevelt Island was formerly known as Blackwell's Island. It's a narrow strip of land in the middle of New York's East River.

We were riding with Judith Birdie, a longtime resident and president of the Roosevelt Island Historical Society. You have the perfect voice for that rating. Oh, that's right. Where are you from? Well, I'm from Chicago. Midwestern neutral voice. Yeah, very neutral. Who are you rooting for on Sunday? Roosevelt Island is small, just 1.5 miles long. The island is technically a part of Manhattan.

We got here on the aerial tram, which travels 250 feet above the river. The trip from Manhattan only takes four minutes. If you didn't want to leave the island, is there everything that you could possibly need here? Yes, we have supermarket, dry cleaner, Mexican restaurant, pizzeria, Japanese, Chinese, American.

falafel, you can stay here and get everything on the island. It just gets boring. We won't take the tram and go to the new Trader Joe's in Manhattan. We got off the bus at the northern end of the island. Here's the octagon. Today, only one part of New York City's old asylum still exists, the octagon. So this is the entrance to the asylum. And now it's the entrance to a luxury apartment house. It's a rental building.

It is my favorite landmark because when they restored the building to make it into an apartment house, the good thing was that they never got rid of all the rubble around it so they could restore all the stonework with the originals. I mean, it seems an odd design for an asylum, an octagon. Oh, no. All our institutions in the 19th century were beautiful on the exterior and hell holes on the interior. Yeah.

So this is where they would, the patients would enter. They had this fancy formal entrance. We walked into a large rotunda with a spiral staircase. So you'd go through a formal entrance and then you, that would stop and you... Then you went down the long corridors and saw reality. The Roosevelt Island Historical Society has an office right inside the octagon. Okay.

Oh, there's a gym. Dance studio, cycles. The apartment complex, which is called the Octagon, has a coffee bar, a game room with pool tables, and a TV lounge. Do you think that a lot of the people who live in the building have any idea about, even though they live here? Uh, no. A lot of people don't know the history. As Judith showed us around the island, she seemed to know everybody. She's lived on Roosevelt Island since 1977,

just a few years after the island was leased by the state of New York for residents to live on. She says that before she moved here, the island was full of mostly just abandoned buildings. But lots of new people started moving to the island around the same time she did. Rent was much cheaper on the island than in Manhattan. Roosevelt Island has been called Roosevelt Island since 1973, when it was named after FDR.

The island was first called Minnehannock by the Indians, the Native Americans. Then when the Dutch ran New York, they called it Varkens Island. A vark is a hog, so welcome to Hog Island. Then the Blackwell family, when they acquired the island, it was named after the Blackwells. And then it became Blackwells Island. In 1828, New York City bought Blackwells Island for $32,500. $32,500.

It was just a few buildings, a bunch of fruit orchards. Stacey Horn. It was beautiful. The way it's described, it just sounds like this lovely, idyllic pastoral retreat. In the early 1800s, New York City was growing. Lots of people were arriving to live there. New York had become America's largest city. And Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan, the oldest public hospital in the country, was overcrowded.

But Bellevue wasn't just a hospital. It was also acting as a prison and a home for the poor in the city's so-called lunatic asylum. And it was so overcrowded to the point of being inhumane, and they realized they had to do something about that.

So they explored various options and they ended up buying Blackwell's Island from the family. And the plan was to build replacement institutions there. But at the same time, they thought we're not going to make any of the mistakes that we did before. And they did a lot of research on replacements.

Like they, well, they called these places lunatic asomes at the time. So I'm going to use that term. There was one in Philadelphia that was considered the model of how you treat people with mental illnesses. It's very humane. And so they thought, okay, we're going to do this and we're going to do this even better. And they'd made similar explorations for every institution. You know, how can we make a better almshouse? How can we make a more humane prison?

The first building New York City completed on Blackwell's Island was the new prison. It was called Blackwell's Island Penitentiary. They also built a hospital, a workhouse, and the asylum.

It actually was a really good idea and very well-intentioned. They really did see it as a sanctuary, as a retreat, you know, to take these people away from Manhattan and all its temptations and dangers and give them a chance to rehabilitate if they're sick or not.

will help them get better. If they have mental illnesses, we'll try to cure them. And if they're convicts, we'll try to rehabilitate them. I mean, they really were proud when they began. They felt, you know, we're going to do this right and we're going to show the whole world. The New York City Lunatic Asylum opened in 1839. At the asylum, doctors and nurses would follow a new type of treatment for people with psychiatric illnesses called moral treatment. At the time,

or just before, the way they dealt with mentally ill, the treatments included bloodletting, putting them in prison, straitjackets. I mean, it was terrible. So moral treatment just meant instead of that, let's

Let's treat them humanely. Let's put them in institutions where they get a nice room with a window and a warm, comfy bed and we'll feed them good food and we'll treat them with love and care and give them things to do during the day that's productive or fun or music and entertainment, you know, things that are enriching. And maybe...

If we do that, they'll get better. And in Philadelphia, where they actually were doing their best to follow that, they were getting better. But Stacey Horn says things on Blackwell's Island started going wrong almost immediately. The first building was built half the size than had been originally planned. So right away, they were overcrowded. On the day the asylum opened in 1839, it almost reached its capacity of 200 people,

So administrators quickly started adding small wooden structures. A lot of their plans quickly started to come apart. It was supposed to be one woman per room, and she would have a window and a nice bed. And what ended up happening is they would put anywhere from four to six women in a room that was meant for one. And they started using interior rooms. So none of those rooms had windows.

And another thing they swore they would never have is windows in the door so you can look in the room, something that prisons have, because they felt the women would feel like they were on view, like being in a zoo. Stacey Horn says the city had also underestimated how expensive everything would be, so they were always coming up with new ideas for saving money.

And some of their ideas were just dreadful. And one idea they had was instead of hiring nurses and attendants for the lunatic asylum, they would take convicts from the penitentiary and the workhouse, and they would work as nurses and attendants in the lunatic asylum. And that just went horribly wrong.

Often, the doctors were recent graduates, or even medical students, some as young as 19, who would move on to better jobs as soon as they could. All the institutions on this island, whether they were, you know, penal institutions or hospitals, they were all run by the same group of men, anywhere from three to six commissioners, but eventually it was just three.

The three commissioners were in charge of hiring and firing staff at all of the institutions on the island, including the poorhouse, the penitentiary, and the asylum, which meant that doctors and other staff had little say in how things were run. Everything had to go through the commissioners, who were in charge of what was named the Department of Public Charities and Correction.

It was an unfortunate association because it created this association that the poor, the mentally ill, and criminals were all somehow one in the same, that the mentally ill were dangerous and the poor were essentially thieves in disguise. And it's an association that persists to this day. And I do want to point out that

Technically, these institutions shouldn't have been only for poor people, though some were directly for poor people. But, for instance, the penal institutions, it shouldn't have mattered what your income was. If you were convicted of a crime, this is where you went. But it ended up being only where poor people went. If a wealthy family had a mentally ill family member, they went to a private institution. If they had a health problem, they went to a private hospital. And

Wealthy people who committed crimes were almost never arrested. And if they were arrested, they were let go with a fine or their cases were just dismissed. And they never, almost never, went to prison. We'll be right back. Nellie Bly wrote that during the day, the women at the asylum were not allowed to read. So instead, they would talk about all the different foods they would eat if they ever got out of the asylum.

It was cold in the asylum, and the women were only given short dresses. It was so cold, the nurses wore coats inside. One visitor reported seeing women whose feet had turned purple from the cold. On one of her first days at the asylum, Nellie Bly and the other women were taken for a walk. They walked two by two in a line guarded by the asylum attendants. They were not allowed to touch the grass. The patients who were deemed violent were tied together and

One woman was dragged along wearing a street jacket. There would be like a chain that would go through the belt, you know, from one woman to the next and tied so that they were like horses in a long line so they couldn't escape. That was...

partially done to make it easier to manage them, but they did have a problem that women, once they got outside, would run straight for the river and jump in and drown. In case visitors came to the island, nurses would tie scarves around the belts to hide the fact that the women were being restrained. The women at the asylum were grouped according to how difficult or sick the doctors or nurses thought they were.

Straight jackets and solitary confinement were often used at the asylum. Nellie Bly had planned to get herself committed to the most restrictive part of the asylum, but when she heard stories from other women about how severely the patients had been abused by staff, some had been left permanently injured, she decided not to risk it.

She saw cases of terrible abuse, like nurses choking inmates there, taking them into a closet so that they can further abuse them. And she would hear the women screaming while in the closet. Oh, and it was terrible because she would say, you know, eventually the screams get, you know, quieter and quieter and quieter until the inmate is silenced. And then she comes out and she's clearly been beaten.

Nellie Bly tried to tell the people in charge about some of the things she'd seen at the asylum. And she would say, you know, this is going on, and nobody would listen to her. And they certainly didn't listen to the victims. For dinner, she wrote that the women were sometimes given some soup, a cold potato, and a piece of spoiled beef. There were no knives or forks. Women who had bad or no teeth couldn't eat.

The patients watched as the nurses ate fresh food like grapes and apples. Some patients died because they were sick or injured and didn't get the care they needed. About 40,000 to 50,000 people were admitted there every year, and 1,000 people died there every year. Stacey Horn says unlike prison inmates who received a sentence,

The women at the asylum had no idea how long they would have to stay and if they would ever go home. One report showed that a majority of patients had been at the asylum somewhere between 10 and 30 years. Nellie Bly wrote about one girl who, every morning, talked about her mother and said, I think she may come today and take me home. She'd been at the asylum for four years. She wrote that she sometimes saw patients who would, quote,

stand and gaze longingly toward the city. When I went to visit the island, I did one thing. I walked the perimeter of the island, and then I faced Manhattan, and it just looks so close. And I'm a swimmer, and I could just imagine someone looking over and thinking, I could make that. I could do it. Except the current in the East River is very, very strong, and pretty much 99% of the people who tried died.

But it looks like you could do it pretty easily. Just right there, right in front of them is this, like, glittering, beautiful island of Manhattan. It must have looked like the Emerald City of Oz. One day, Nellie Bly had a visitor. Her newspaper had sent a lawyer to try to get her out. She told the lawyer that the first thing she wanted was something to eat. She said goodbye to the women at the asylum. She wrote, "'There is a certain pain in leaving. I had been one of them.'"

It seemed intensely selfish to leave them to their sufferings. Nellie Bly wrote about what she'd experienced inside the New York City Lunatic Asylum. Her report ran as a serialized expose in the New York world. It was widely read. People were shocked, and the city began investigating the conditions at the asylum. As a result of her reporting, more staff was hired, including female physicians, although they didn't stay long. A new fire escape and a bathhouse were planned,

And the patients got to make coats for themselves out of blankets. Someone thought it would be nice for the women to have birds. 25 canaries. They increased the budget for the lunatic asylum. But it was something like, it wasn't enough. It didn't really have any effect on the conditions there. It was just not enough to even be a blip in their lives. Exposé after exposé.

would come out about the lunatic asylum and the other institutions, and the public would go, oh, this is terrible. And the city would make some sort of effort to address the situation, and it was always enough to get the outraged people to go, okay, good, something's happening, something's going to get better. But it never really got very much better.

By 1901, all of the patients at the asylum had been moved to other institutions. Nellie Bly continued working as an undercover reporter. She went undercover trying to bribe a corrupt lobbyist, got herself sent to prison, and investigated the practice of buying babies on the black market. Later, she worked as a correspondent during World War I. She eventually published her reporting from the Blackwell's Island Asylum as a book.

Today, at the northern tip of Roosevelt Island, there's a large monument to Nellie Bly. A sculptor created five faces of different women. And she decided that it was more than just Nellie Bly, and she represented all women. So we have these beautiful seven-feet tall heads. It's called the Girl Puzzle. The monument is named after Nellie Bly's first published headline. So we just have Nellie all over the place.

Yeah, Nellie's our girl. If you want to learn more about what was happening on the other end of Roosevelt Island from the asylum, we have a special bonus episode for subscribers of our new membership program, Criminal Plus. In the bonus episode, we'll be taking a closer look at the island's prison.

in an annual Christmas show performed at the prison in the 1920s and 30s. They would take labels off of tomato soup cans, soak them in water, and use the red ink to create lipstick and rouge. They would also crush up chalk to make white powder.

Sometimes they would use shoe polish as mascara and eyeshadow. So really expressing a great deal of ingenuity to reclaim their queer identity despite adversity and oppression. To hear more from playwright Travis Russ, who learned about the island's holiday show while working on his new play, The Gorgeous Nothings, sign up for Criminal Plus.

If you sign up for Criminal+, you can also listen to Criminal episodes without any ads. To learn more, go to thisiscriminal.com slash plus. Criminal is created by Lauren Spohr and me. Nadia Wilson is our senior producer. Katie Bishop is our supervising producer. Our producers are Susanna Robertson, Jackie Sajico, Lily Clark, Lena Sillison, Sam Kim, and Megan Kinane. Engineering by Russ Henry. This episode was mixed by Emma Munger.

Julian Alexander makes original illustrations for each episode of Criminal. You can see them at thisiscriminal.com. Stacey Horne's book is Damnation Island, Poor, Sick, Mad, and Criminal in 19th Century New York. You can sign up for our newsletter at thisiscriminal.com slash newsletter. And if you like the show, tell a friend or leave us a review. It means a lot. We're on Facebook and Twitter at Criminal Show and Instagram at criminal underscore podcast.

We're also on YouTube at youtube.com slash criminal podcast. Criminal is recorded in the studios of North Carolina Public Radio, WUNC. We're part of the Vox Media Podcast Network. Discover more great shows at podcast.voxmedia.com. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal.