Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

This BBC podcast is supported by ads outside the UK. Tariffs, inflation, recession, layoffs, your 401k, your cousin's crypto. Feel like the world's on fire? Make it make sense.

Cut the noise. Think Rockford, Illinois, where rent won't crush your soul and good jobs meet a great cost of living, where your commute's short and your weekend's long, where homeownership is actually within reach, and downtown, walkable, river views, craft beer, art, live music, and all the vibes. Make sense? You're made for Rockford. Find out why at madeforrockford.com.

Join now at Senesta.com.

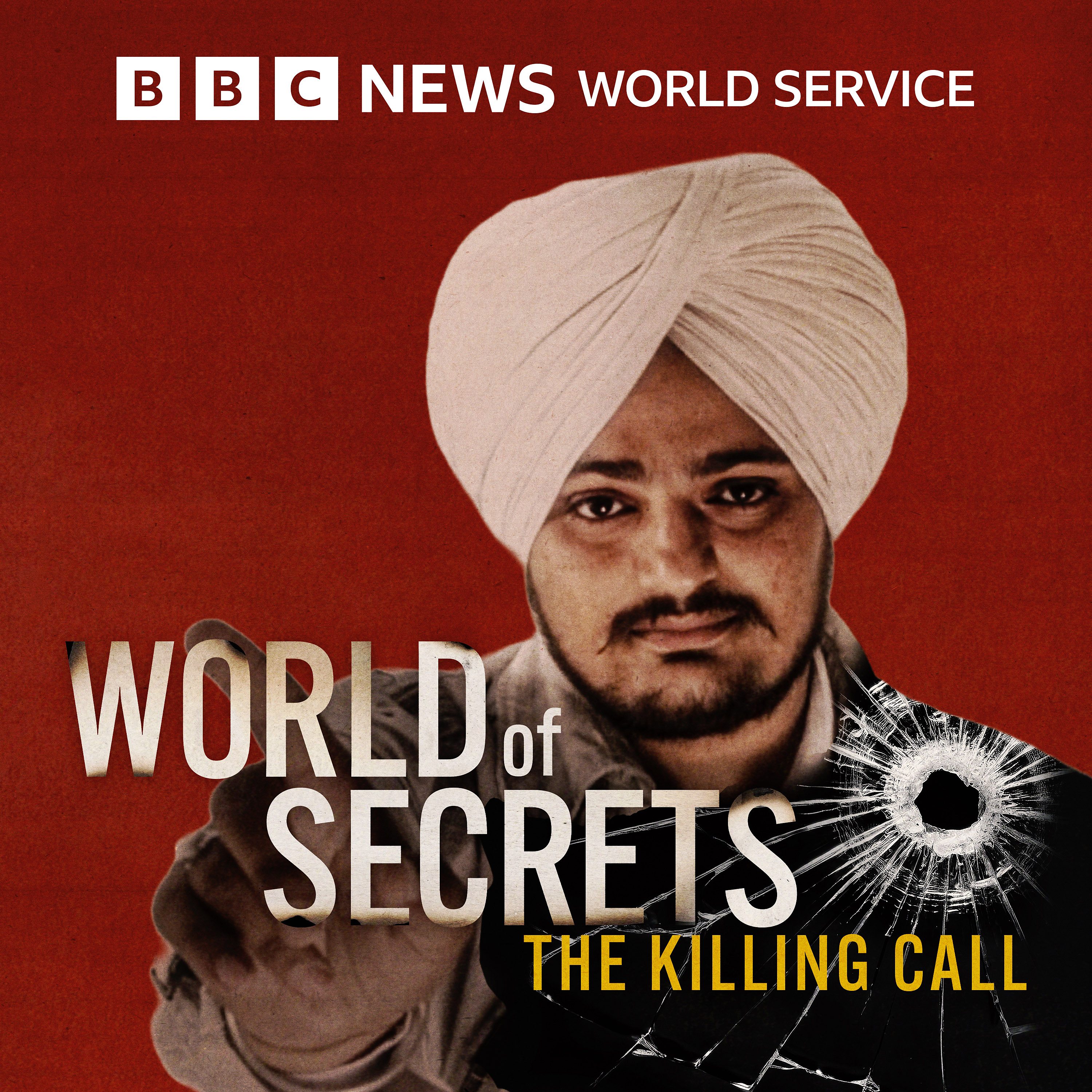

Terms and conditions apply. Before we start, don't forget there are seven previous seasons of World of Secrets, the BBC's global investigations podcast. They're available right now and are waiting for you once you've finished this episode. It's two days after Sidhu Mooseyala was killed. In his small village of Moosa in northern India, the streets are swollen with people.

Thousands have travelled here for his cremation. Queues stretch along the usually quiet roads in the scorching May heat. You see an ocean of fans there who have landed up at his village. You know, to see people coming from far off places, from all over the country they came. Some may have come from abroad also.

Millions are tuning into the live news feeds. Among them, the journalist, Jipinderjit Singh. Everyone was crying, Aisling. You could see the tears in the TV broadcasts on YouTube and everywhere. I think not just me, every Punjabi that day was glued to the TV. Suddenly, there's movement at the front of Sidhu's family house. The crowd surges forward. Sidhu's favourite tractor pulls onto the road

Behind it is a trailer carrying a glass coffin. The trailer is covered with flowers. The crowd throws more flowers. There are chants of long live Siddhu Musiala.

But there's anger too. People want to know why wasn't he better protected? His parents sit on the trailer beside their son's body.

grief-stricken, leaning over the coffin, laying their hands on it. The funeral procession makes its short but slow journey from the family house to the family field where he'll be cremated.

Here, thousands more mourners wait in the midday sun on the scorched brown grass around a pyramid of firewood. This is the funeral pyre where they'll place his body. On the way to the cremation site, something extraordinary happens. Sindhu's father stands on the trailer that's carrying his dead son's body.

He's above the crowd and thousands of eyes watch as he lifts his turban from his head and holds it out towards the people. You know, his hands were shaking and he took a circle, you know, all around him where he was offering his turban. And I remember people around him went like, no, no, no, please don't do this. There's a sense of shock.

For many Sikh men, their turban is a sacred sign of their faith. You only take it off in the privacy of your own home, never in public. Taking off his turban, he was offering some gratitude he will not be able to offer in births. It was from his deepest inside, you know, something which he can't speak.

Watching the funeral here in London, that moment, it ripped my heart apart because as Sikhs and as Punjabis, we know what that means. Yeah, it was a very difficult thing to do. It was a gesture of pleading also, you know, pleading for arrest of the killers, pleading for justice, justice for his son. There's so much grief, so much anger, so many questions.

We need to find the gangster who says he's responsible for the killing of Sidhu Musela. We need to find Goldie Brar. This is World of Secrets, Season 8. The Killing Call, a BBC World Service investigation. I am investigative journalist Ishleen Kaur. And I'm broadcaster and DJ Bobby Friction. Episode 3, The Gangsters. The gangsters are here.

Jasveer Tandy and his family live in a modern house with a lawn and a garage on a residential estate in a suburb of Vancouver. Like Sidhu and the many other Punjabis who live here, Jasveer left India to make a new life here in Canada.

Now, in his early 30s, with a quick smile and an open, expressive face, he works doing what so many Punjabis who come to Canada end up doing, driving trucks long distance. And he's doing well. It's a double-seater.

As Jasbir plays with his two-year-old son in their large open-plan kitchen, he tells me how he and Sidhu became friends. And how, for a while, Sidhu lived here with them. For three months in 2018, just as Sidhu's music career is taking off, this house is the place that Sidhu calls home.

Even before I met him, I was his fan. And then when I met him, he was so gentle, like a very shy guy. Not like his songs. He was not aggressive like that. So he was very soft and kind-hearted guy to

To my mom, he was like, "Mom, give me hair, tie my hair, give me oil, like his own mom." Jasbir just said that whenever Sidhu would come here, he would ask Jasbir's mom to comb his hair, to oil his hair, help him tie the turban. And it is traditionally what a Sikh mom would do for her child.

I think he was born a rapper, like representing his own life in the songs. He was so inspired and then he said he's going to bring Hollywood to Moose Up End and then it's happening. He was so passionate. Even like if you go to a washroom, he wrote a song. Sidhu is living with Jasbir when he plays that show in Edmonton, the one we heard back in episode one, where he comes onto the stage and talks about receiving death threats.

Just me, because you knew Sidhu so well. Do you know of any threats that he got? Everyone got threats in Punjabi industry, I believe. Yeah, and Sidhu got start from 2018. And that time he sang a song, East Side Flow. And he said, So yeah, that's why he wrote the song.

That song that Jaspee is talking about, it translates to when I wake up with my morning tea, I get an extortion call or I get a threat. I'm a truck driver and I used to go to Calgary that time and he came with me on a truck. That East Side Flow song, he wrote in a truck. Yeah, when we left Calgary and then after 45 minutes, he had a song.

Did he ever come to you, you know, like after a call? Did he share anything like that? No, he never tell like any details. He never tell anyone. Even his parents, he never tell. Just we were talking outside and you said whenever Sidhu would leave your house, he would send you his location.

Was he scared of something? What was he scared of? No, he was not scared. But he always said that, "Bro, one day I'm going to die with a bullet." I know that. That was his worst. And then he got those bad dreams like, "Oh, someone is killing him." Yeah. Were you worried about him as a friend? Yeah, we always got worried. We told him, but he said, "No, no, no, bro. It's okay. It's okay." He was not scared of death. He said, "One day we're going to die. It's okay."

It's around the time Sidhu's living with Jaspia that this gawky Punjabi student is being catapulted from village boy to global megastar. Sidhu Muslala! And with big success comes big money.

Now, when he travels, it's in a convoy of cars. Stretch limos, sports cars, SUVs, and around him an entourage of young Punjabi men with freshly groomed beards and dark shades. He's living the life of a star. But fame makes you a target, and so does money. Those threatening calls and messages, they just keep coming.

When Sidhu's old university friend Pushpdeep sees him again two years later, he notices a big change. He had become like a whole lot of a serious guy at that point. I had spent so much time with him, I could look at his face and I could say that from his face that he had some problems.

Pushpdeep never imagined that Sidhu's problems could be gangs. He used to tell me to be safe and stay away from this kind of stuff. And I know that he wasn't that kind of guy. But Pushpdeep does feel anxious about the company his friend was keeping. He was ruling the singing industry at that point and he was on the peak and people just want to take advantage of his fame.

He was always surrounded by so many people that he didn't get a chance to converse properly to all those people that were literally so close to his heart. He was always surrounded by 10 or 12 men and he couldn't afford to be vulnerable in front of those guys because, you know, he was such a big artist and such a strong artist.

and people would think that he's weak. Not looking weak, bravado, honour, machismo, it's all an essential part of Punjabi male culture. There we go now.

It's been a big part of the gangster rap trend in hip-hop too. In Sidhu's videos, there's big brawny men looking tough, flexing their muscles, luxury cars, police chases, guns, so many guns, and there's Sidhu constantly looking down the camera lens, looking directly at you, almost asking you to start it, to bring it to him.

You know, there's a move he does where he slaps his thigh. It's a move from Punjab's national sport, kabadi. We call it a tapi. It's provocative. It's aggressive. It means, come on, bring it on.

And all of this playing out in Sidhu's videos sees Sidhu literally playing the role of being a gangster.

Violence is something lots of rappers have been asked about in interviews. And Sidhu's no exception. Here, the interviewer asks... People say your songs are about gangsters, about beating people up. They're arrogant. How do you respond?

I've been listening to hip-hop since I was in the sixth grade. And it is violent. But if someone does something wrong after they've been listening, maybe it is the bad company that they're keeping, not the music. I've been listening to hip-hop for years, and I've never shot anyone. But the trouble is, Sindhu is working in a world where real gangsters operate.

Real gangsters with real guns who make threats with real consequences. Sidhu Musawala, in fact, was someone who had a certain amount of threat from gangsters. When he was facing severe death threats from several gangsters in the country, the Punjabi singer was gunned down.

Ever since that day in London, when my brother called from Canada and together we were watching the rolling news coverage of Sidhu's death, I've been determined to find out why Sidhu was killed. I've spoken to lots of people about this. His friends, journalists, politicians, people in the music industry, and almost all of them are fearful. I hear it again and again. They were threatening Sidhu. They were asking for the rights to his songs.

It's too frightening even to use the word because they means gangsters. I realized the only person who can tell me really what's going on is someone from that world. Someone who is a gangster himself. It's taken me months of chasing, hundreds of messages and calls, but at last a major player in the world of Punjabi organized crime has agreed to talk to me.

We're not going to identify him for security reasons. We agreed to meet in a downtown hotel in a North American city to talk, off the record. I'm there early, not sure if he'll show. I sit waiting, watching the door, my stomach in knots. We've agreed to meet at 9pm. The hours tick by. 10 o'clock, 11 o'clock. When he finally arrives, it's one in the morning.

He steps into the lobby among the well-heeled late diners. He's in his late 20s. He's wearing torn jeans and designer trainers. His eyes burn into me. After we've talked for a few minutes, he asks if he can show me something. Out of his pocket, he takes an object wrapped in a handkerchief. It's a revolver. He unwraps it and smiles, watching for my reaction.

And then he re-wraps it and carefully places it back in his pocket. When it comes to recording an interview, he insists he won't do it face-to-face. Who's ringing now?

So we agree to talk later, online. He tells me those threat calls, like the ones that Sidhu got, are usually made to extort money. Or sometimes when they're talking to musicians to get the rights for songs.

The rewards can be huge. Siddhu's music alone has had billions of streams and views. I ask, how do they decide who to extort? We're talking in Punjabi, so an actor is voicing what he says. I have got a network of people in different cities across India and they give me contacts and information. We never ask for money from people who cannot afford it.

But if someone is worth $100 million, then you know, we will ask them for $5 million. We never threaten on the first call. We just say, politely, we need the money. And if they do it, if they pay, everything's fine. If they don't, well, then we know what to do to get the money. I press him. What does he mean? What do they do? All he'll say is, whatever we want.

But we know. There have been too many reports of killings in Punjab and in Canada. And reports of their well-to-do houses of musicians and businessmen being shot at.

I push him. He's killed people. He's a wanted man in India. Shouldn't he be behind bars? Where does all this end? He's cold. He says, we're going to keep doing this. Everyone's end is death. And is it true that they target musicians? Yes. Singers get extortion calls and they have to pay. And it's not just singers. Wealthy businessmen get extortion calls too.

Then he says something that really surprises me. We gangsters have a lot of singers who we speak to. They're friends, but that doesn't mean they're involved in gangs. It's like any relationship. We meet, we chat, we mix in the same circles. We help each other. If they need help, they ask us. Is that right? Do some musicians and gangsters talk to each other? Are some even friends? He makes it all sound so normal.

I ask him, do musicians ever ask gangsters to help protect them against other gangsters? Yeah, that does happen. They have to pay protection money, of course. And when they get extortion calls, they have to pay. It happens all the time. After speaking for over an hour, we disconnect. I'm exhausted. I'm reeling from what I've heard.

If contacts between musicians and gangsters are as widespread as he says they are, could it be Sidhu was talking to gangsters? Did he know some of them? Did he even count some as friends? There was public outrage after that press conference on the day that Sidhu died when police said that he'd been killed because of gang rivalry. People took it as implying Sidhu himself was somehow linked to the gangs.

The head of Punjab police came out quickly to say he'd been misunderstood. But did links to gangs play a part in his death? We need to know. Our strongest lead is the person who says he was responsible for Sidney Murciela's killing. The gangster, Goldie Bra. The problem is, we're not the only people trying to find him. There's an international arrest warrant out for him. The last anyone heard, Goldie Bra was in Canada.

I get in touch with the journalist who got the call from Goldie Bra on the night Sidhu died. That call where Goldie Bra takes responsibility for the hit. He gives me the number that he called Goldie Bra back on that night. I send a message. I explain who I am and why I want to talk to him and ask if he'll speak to me. Then I wait by my phone.

The hours turn into days, then weeks. There's silence. Nothing. It's a dead end. Then suddenly, two months later, out of the blue, I get a message back. All it says is, we've got your message. We've passed it on to our brother, Goldie Brar. The atmosphere of Mexico Beach is very quiet and slow. And that's a good thing.

There's no hustle and bustle like you have at most beaches. I think we're one of the last truly small beach towns in Florida. That small town attraction where you know the owner of the hardware store, you know the lady that delivers your mail. I don't know any other place along the coast that's like that. You can rent a bicycle or bring your bicycle. You can ride from one end of town to the other.

and experience the shopping on one end, experience the beach on the other end. It's a very unique place. Experience our character and unforgettable spirit at MexicoBeach.com

Terms and conditions apply.

Are you struggling to find an effective mental health medication? Meet the GeneSight test. Whether it's medication for anxiety, depression, or ADHD, the GeneSight test is a genetic test that analyzes how your DNA may affect medication outcomes. Along with a full medical evaluation, test results can inform your provider with valuable insights to help guide treatment. Your unique genetic blueprint may also lead to significant savings on medications.

According to a 2015 study published in the Journal of Current Medical Research and Opinion, patients who received GeneSight testing saved on total annual medication costs, took their medicine more regularly, and were on fewer medications by the end of the study compared to those who received regular treatment. Ask your provider about the GeneSight test today and move forward on your journey to mental wellness. Or visit genesight.com for more information.

Again, jeansight.com for more information and to move forward on your journey to mental wellness. To understand the gangsters and how they linked to Sidhu's journey, we're in Punjab, 2018. It's always amazing to see Sidhu Musiala on stage. He's got such presence. Put your hand to the front of the knee. Pizza! Jets!

But this concert is special. It's his first concert back home. There's huge excitement amongst the young crowd. Greetings, people of Chandigarh, Siddhi tells them. This is my first performance in India and I salute you.

I think he was booked for a few other concerts throughout Chandigarh, but he chose to come to Punjab University first. That was a space that he wanted to capture. I personally feel Sidhu came to capture the imagination of Punjab's youth. Today, Raja Sanmaanbir Singh is a media advisor to some of Punjab's leading politicians. But back in 2018, he was a student at Punjab University and he helped organise the show.

It was amazing. Usually, you know, you prepare for 4,000, 5,000 students. Sidhu probably had more than 12,000, 14,000 students come up. It was way beyond our expectations. We were not prepared for that. Ten minutes before Sidhu showed up, there was just a sea of people standing. Punjab University has a special place in Punjabi society. It's not just where young people come to study, it's a power centre

Somewhere that prepares future political leaders, industrialists, academics, writers and artists. What happens here matters. It's a powerful platform. And for some people, giving that platform to someone like Sidhu could be dangerous. Which is why one university professor tried to stop him performing.

So there's this one professor, he got a stay against Sidhu Musawala from the High Court, that he cannot sing any of his songs which glorise violence, gun culture. So all of the songs that he was actually famous for, that people knew him for, he didn't sing a single song. Standing on stage, Sidhu speaks to the crowd.

Recently, people said Sidhu's going to bring guns to the concert, that he glorifies weapons. But this is a democracy. You've got the right to disagree with me. It's fine if you oppose me.

I think that was the first time people got to see the resistance to Sidhu. There was a faction against Sidhu Mosewala performing in Punjab University and there was a faction that really wanted him to perform in Punjab University. The faction that wants Sidhu to perform wins, of course. And when Sidhu steps onto the university stage, even the presence of the police doesn't stop the students going wild. His music...

Now, let's talk about Shravan.

These days, Sidhu says, you must have seen they're after all of us singers, saying we're writing songs about alcohol. Well, I wrote a song today. He holds up a piece of paper, waving it to the crowd. It's called Chitta. Do you know what Chitta means? It means truth.

I'm not taking sides. I'm just telling the truth, he starts to sing. They say there are songs about alcohol on TV, but I want to know why are there more liquor stores in Punjab than there are schools?

Why don't you close the businesses of people making money by selling addiction? You know, we'll stop singing songs about weapons when you have the guts to ban weapons. Sidhu reached out to those young minds, Punjab and especially the youth of Punjab. They're directionless. If a Punjabi youth who's aged 15, 16, 17, he feels he has got no opportunity in life if he stays back in India, in his village in Punjab.

There's this misconception in his head that he flies off to Australia or Canada, anywhere abroad, and everything was going to be sorted for him. Sidhu's music, it was a resurgence for them. It provided that motivation that was missing. So yes, everyone's listening to Sidhu Mooseyala. He really affected the lifestyle, the culture of not just me, a lot of people. This is the moment that Sidhu Mooseyala starts articulating what many young people in Punjab want to hear.

He's becoming someone they want to listen to. Someone with influence. And Punjab University has another role in this story too. It's another busy day in the newsroom at the Tribune newspaper in Chandigarh. Journalist Chipinderjeet Singh is now the paper's deputy editor.

Japindarjeet's been covering Punjab's gangs for years. Yes, since the advent of gangsterism from 2012 onwards, when this menace really took over, every part of India has its own gangs, whether it is Uttar Pradesh or Delhi or Haryana. So gangs are everywhere. It's only that Punjab is, you know, one of the more developed areas.

It's the opium trade in nearby Afghanistan, Japindarjit says, that has fed this growth in Punjab's criminal underworld. The drugs flow south, across the border, from Afghanistan into Pakistan and then down into Indian Punjab.

Suddenly, Punjab became number one in country as far as drug smuggling was concerned. Before that, Punjab was the transit point for drugs. But from that, it started becoming the consumption point also, 2012 onwards. And with the drugs comes the money. Money that needs to be laundered.

2012-13 onwards, there was a big boom in real estate in Punjab. Big boom in liquor industry, big boom in sand mining also. These are the businesses which we all feel have lot of black money or unaccounted money.

So all these things, you know, and there was a huge tug of war between two main political parties, the Congress and the Akalis. And it was very common for them to use, you know, special muscle men, if we can use the word, or even goons. And these were all youngsters who were taken from colleges and universities. Those muscle men came out of student politics and several of them had some kind of a criminal history.

This group includes one particular young student from Punjab University, a man about the same age as Sidhu from a relatively well-to-do family. He got involved in student politics, but words became actions. Disagreements became fights. There was violence with other student groups. He was a student leader turned gangster and he was involved in several crimes.

And he was kind of high profile, but not that high profile. Of course, he was in news for threatening Bollywood star Salman Khan. He was sent to prison in 2014 on charges of attempted murder, where he's been behind bars ever since. His name is Lawrence Bishnoi.

And incredibly, being imprisoned doesn't seem to have stopped his criminal career. Quite the opposite, in fact. From behind bars, Lawrence Bishnoi is alleged to have grown a criminal network whose activities reach from India to Canada, and maybe further. Today, on his payroll, his own people say they have several hundred people. Punjab has, you know, about 500 gangs.

which are administered by 10 mother gangs and Lawrence Bishnoi's gang is one of those gangs. Out of these 10 gangs, 4 are aligned with Lawrence and 4 are aligned with his biggest rival, the Bambiha gang. And the gang wars which had led to 16-17 killings, we had reported those also.

But then something happens that supercharges Lawrence Bishnoi's profile. Throughout this series, we've heard about the threatening calls that Sidhu was receiving. We can't know for sure who was calling or if they all come from the same source. But ever since my hotel lobby meeting with that gangster, I've been trying to find out if someone in the gangs had a hold on Sidhu.

After all, Sidhu was one of Punjab's highest earning musicians. He seems like an obvious target. I've spoken to so many people about this. Finally, sources close to Sidhu have told me that for at least a couple of years before he died, Sidhu was talking to a Punjabi gangster.

Do you remember that phone call that we heard in episode two? The one to a prison in Delhi, an hour after Sidhu Musiala was killed. When the caller said, "We've killed the Sikh, we've killed Sidhu Musiala." And the prisoner replied saying, "Cut the call."

Well, that prisoner was the same gang leader that Sidhu Musiala had been talking to. That prisoner is the leader of the gang Goldie Bra is part of. That prisoner is Lawrence Pishnoi. Why did Lawrence Pishnoi become Sidhu Musiala's enemy? That's next time on World of Secrets.

This has been episode three of five of The Killing Call, season eight of World of Secrets from the BBC World Service. The Killing Call is a BBC Eye production. Leave us a rating or a review if you can. It really helps. And follow or subscribe so you get every episode automatically.

World of Secrets The Killing Call is presented by me, Ishleen Kaur. And me, Bobby Friction. It's produced by Louise Hidalgo, Rob Wilson and Eamon Kwaja, with script advice from Matt Willis. Sound design and mix is by Tom Brignall. And the executive producer is Rebecca Henschke. The editor is Daniel Adamson and the BBC i-Series producer is Ankur Jain.

Original music by Ashish Zakaria. Fact-checking is by Curtis Gallant. Additional research by Ajit Sarati and Arvind Chhabra. The production manager is Dawn MacDonald. And the production coordinator is Katie Morrison. Many thanks to the BBC World Service commissioning team that's behind World of Secrets. And thank you for listening.

Decades ago, Brazilian women made a discovery. They could have an abortion without a doctor, thanks to a tiny pill. That pill spawned a global movement, helping millions of women have safe abortions, regardless of the law. Hear that story on the network, from NPR's Embedded and Futuro Media, wherever you get your podcasts.