Trouble at The Baltimore Sun, and the End of an Era for Pitchfork

On the Media

Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

Guys, is this how it ends? Is this the sign of the death of music reviews? With huge layoffs at the beloved music review site, Pitfork, and at the LA Times, this year gets off to a bad start for journalism. From WNYC in New York, this is On The Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. And I'm Michael Lohinger. Meanwhile, The Baltimore Sun was sold again.

After the last sale, the hedge fund owners kept the paper's staff mostly intact in order to go head-to-head with a local rival. There's ego involved here, right? I mean, I'm guessing. So you're saying this was a bleep measuring contest? Yeah. The Sun's newest owner has Baltimore locals feeling less than optimistic about their paper's future. There's a tradition. In the summertime, when you go pick up a dozen crabs, you lay the newspaper on the table to...

crack the crabs on, but I think the sun has meant more to the people of this market, of this city, than just a place to lay your crabs on. It's all coming up after this. On the Media is brought to you by ZBiotics. Tired of wasting a day on the couch because of a few drinks the night before? ZBiotics pre-alcohol probiotic is here to help. ZBiotics is the world's first genetically engineered probiotic, invented by scientists to feel like your normal self the morning after drinking. ZBiotics is the world's

ZBiotics breaks down the byproduct of alcohol, which is responsible for rough mornings after. Go to zbiotics.com slash OTM to get 15% off your first order when you use OTM at checkout. ZBiotics is backed with 100% money-back guarantee, so if you're unsatisfied for any reason, they'll refund your money no questions asked.

That's zbiotics.com slash OTM and use the code OTM at checkout for 15% off. This episode is brought to you by Progressive Insurance.

What if comparing car insurance rates was as easy as putting on your favorite podcast? With Progressive, it is. Just visit the Progressive website to quote with all the coverages you want. You'll see Progressive's direct rate. Then their tool will provide options from other companies so you can compare. All you need to do is choose the rate and coverage you like. Quote today at Progressive.com to join the over 28 million drivers who trust Progressive.

Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and Affiliates. Comparison rates not available in all states or situations. Prices vary based on how you buy. One key cards earn 3% in one key cash for travel at grocery stores, restaurants, and gas stations. So the more you spend on groceries, dining, and gas, the sooner you can use one key cash towards your next trip on Expedia, Hotels.com, and Vrbo. And get away from...

groceries, dining, and gas. And Platinum members earn up to 9% on travel when booking VIP access properties on Expedia and Hotels.com. One key cash is not redeemable for cash. Terms apply. Learn more at Expedia.com slash one key cards.

I'm Maria Konnikova. And I'm Nate Silver. And our new podcast, Risky Business, is a show about making better decisions. We're both journalists whom we light as poker players, and that's the lens we're going to use to approach this entire show. We're going to be discussing everything from high-stakes poker to personal questions. Like whether I should call a plumber or fix my shower myself. And of course, we'll be talking about the election, too. Listen to Risky Business wherever you get your podcasts.

From WNYC in New York, this is On The Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. And I'm Michael Olinger. 2024 has been very hard on the news business, and it's only January. The Baltimore Sun has now been sold to David Smith, executive chairman of

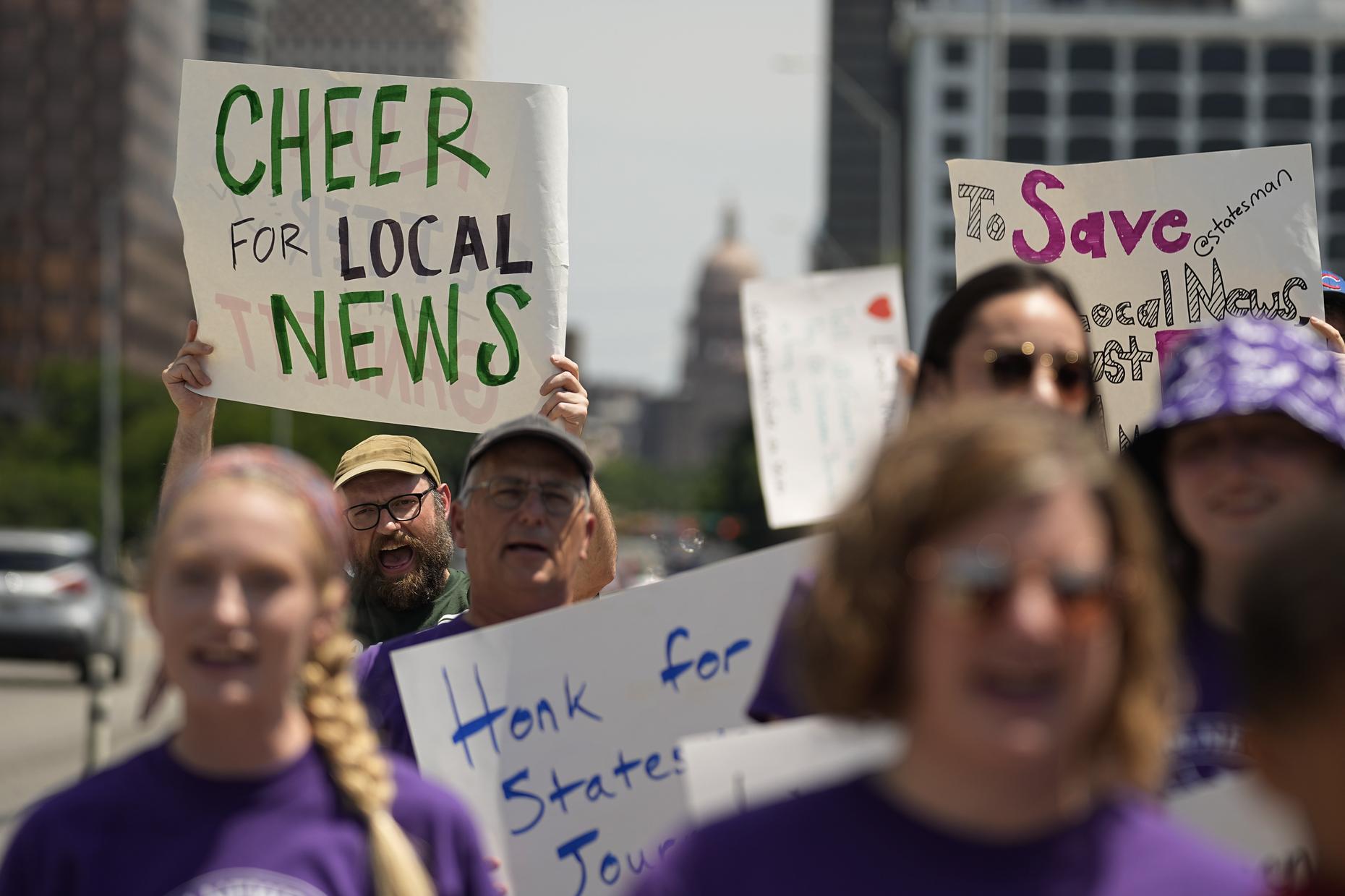

Sinclair Broadcasting. Also this week, the Los Angeles Times announced yet another round of layoffs. The Times Guild Bargaining Committee tweeting Thursday, quote, folks, this is the big one. The Guild called for a Friday walkout, the first such action since the paper started in 1881, to protest a projected 20% staff cut, about 100 jobs.

This on top of a cut of 74 positions in June. Meanwhile, Sports Illustrated just laid off most of its staff. And then there's this. Guys, is this how it ends? Is this the sign of the death of music reviews? January 17, mark the day. Pitchfork is being folded in to GQ.

More on that one later in the show. In recent years, billionaire owners have snapped up outlets like the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, the Atlantic, and others. But three of the top newspaper chains in the country are currently owned not by individuals or families, but

by private investment firms. According to Margot Suska, assistant professor of journalism, accountability, and democracy at American University, we're currently in the private investment era of media. Private equity firms and hedge funds may function differently in the marketplace, but Suska says they have a similarly ravenous approach to buying up news outlets and selling them off for parts.

Suska, author of Hedged, How Private Investment Funds Helped Destroy American Newspapers and Undermine Democracy, debunks the notion that it was solely the dawn of the internet that failed local news. The loss of advertising revenue was devastating for the U.S. newspaper industry. But in the early 2000s and in the mid-2000s, newspapers could have competed with those sites.

Instead, with that pressure from private equity investors, there was very little digital innovation. Rather than compete digitally, they merged and they acquired. And that put them billions of dollars in debt. You've observed that the newspaper industry isn't in crisis because its business model changed.

That's right. Profit has been part of the American newspaper system as long as we've had newspapers. But

But profit in the name of democracy looks much different than profit made in spite of it. And what we've had from 2003 onward is a crop of investors and owners that care very little about how a newspaper works.

functions in the community. You know, Hearst and Pulitzer were very concerned about money, and they made oodles of money. But the ownership structure that we have now, it's profit with no consideration for quality journalism. So what defines the private investment era?

over-harvesting, which is just a focus on extreme profit, mergers and acquisitions, and then a massive amount of debt. People are the most expensive line item in any newspaper. So it's no shock that to maximize profits, the number one thing to go out the door are bodies.

You single out three investment firms for particular damage done to local news, and you give them each a moniker. First, there's Alden Global Capital. You call Alden the vulture. Well, Alden is part of Randall D. Smith's financial universe. His hedge fund was described as, quote, profiting from other people's misery by trading the stock and debt of troubled companies. The

Alden Global Capital gets its negative reputation really through the efforts of the Denver Post staff. In 2018, the staff rebelled and they ran a front page story devoted to how terrible conditions were at that newspaper.

They had a front page color photo that showed the impact of the layoffs on what was one of the best regional newspapers in the country. And they blamed Alden Global Capital.

It was revolutionary at the time. And it was a wake-up call for many in the industry to say, Alden is a vulture, profiting off of the destruction of newspapers. How does it profit? So remember, when they buy up companies, they gain buildings, land, printing presses, assets that are worth in the tens of millions of dollars.

they also profit off of what's left of ad revenue and circulation revenue. For as long as it lasts, I guess.

Well, the U.S. newspaper industry gets described as this tired, dead business. But publicly traded newspapers in 2020 generated $8 billion in ad revenue and another $11 billion from circulation.

But the demands of shareholders for greater and greater profit meant that a profitable business simply wasn't good enough. It still had to be sold off for parts.

But what you have to remember about hedge fund ownership is that you no longer have to worry about shareholders. Under hedge fund ownership, you've got just a few guys, right? So yes, you're right. Is it a smaller pie than it was in 1999 or in 2002? Absolutely. But Alden Global Capital in 2017 made $170 million in profits. When you've got a company that's only a few people

That's a lot of money to spread around. So they're the vulture. They snapped up the Chicago Tribune, the San Jose Mercury News, the Orlando Sentinel. There's Chatham Asset Management, which you think is the least worst investment firm in the space. It bought McClatchy and the Miami Herald. And then you've got what you call the phantom fortress investment group.

Fortress bought the Gatehouse newspaper chain that was the largest in the U.S. in 2005. They openly said that they had no idea what they were doing running a media company and immediately started laying people off.

And they went through this whole cycle of the private investment era. They would profit from cutting news. They would merge and acquire. They got into so much debt, they had to declare bankruptcy, which the debt was then wiped out.

through Chapter 11 actions. Now, you point to how enabling our bankruptcy laws were to the Sherman's march to the sea they were doing in the newspaper business.

The bankruptcy law enabled Gatehouse to emerge from its bankruptcy even stronger, an even larger owner. The thing that's so fascinating is that after the Gatehouse-Gannett merger, Fortress Investment Group was able to collect 10%.

tens of millions of dollars through both dividends and management fees from a company that laid off hundreds of reporters and claimed that it was in dire straits. So these are functions and conditions of the market. And we have an existing regulatory system that's designed to put guardrails on

media ownership that's designed to put caps on the number of TV stations and newspapers that one company can own in one city, right? But those have essentially been decimated. We have an antitrust system that should be working to stop a very small number of companies from operating in one sector. That could be put into place. The Federal Trade Commission has merger guidelines that

We need to enforce the structures that we have. Why do you think local news was made a target by these firms? Aren't there more lucrative industries that they could parachute into? Newspaper companies still beat S&P 500 averages. They outperform the stock market.

But I think that there are other reasons as well. Controlling the local news marketplace means that you get to control the narrative when it relates to other businesses that you might be involved in. Do you have examples where exactly that has happened? Because that's important.

So Fortress Investment Group, a private equity firm based in New York, is also very heavily invested in rail. And in Florida, there were two counties along the Atlantic coast that had filed lawsuits against efforts to expand rail. They had claimed public safety implications. There were environmental implications there.

So Fortress Investment Group, which of course was the owner of the Gatehouse newspaper chain, Gatehouse buys newspapers in Florida. So that all but stops reporting on the public safety implications, the environmental implications of these rail deals. Those lawsuits ended up getting dropped. That's the real threat, I think, of having this kind of ownership.

You drew attention in your book to the death of Daniel Prude after an encounter with police in Rochester in 2020. It was months before the killing of George Floyd, and it wasn't covered in the press there. You see the Prude case as one in which a well-staffed newspaper unencumbered by a corporate owner's profit margin could have pursued that story.

If there had been a reporter, they would have had sources, bureaucratic paperwork to follow. There would have been neighborhood chatter after the incident. There was a videotaped encounter, an ambulance ride, a hospital visit, and even by April of that year, an internal police report. None of that was covered?

None of it was covered. And the case only came to light after his lawyers for his family filed public records requests to get access to the case.

I'm not blaming the Rochester, New York newspaper, which is owned by Gannett, because they have faced layoffs. But the point that I'm trying to make is that in a well-functioning press system, those are the kinds of stories that we learn about. Imagine cases like that nationwide that go uncovered, local corruption that goes uncovered because there's no reporter involved.

Watching that meeting, filing the public records requests to make sure that those actions are being watched, that's a byproduct of a newspaper system that is completely broken. Your research has found that there is profitability in local news. However polarized people may be, they crave it. Yes. You concluded your book...

by saying, quote,

All eras must end, meaning the private investment era. What kind of era do you propose?

Well, there's a lot of hope in the nonprofit model, but when philanthropy goes away, it will eventually, we're going to need more audience support. We're also going to need to address as a country, government funding to create a digital news ecosystem that supports objective civic coverage.

coverage. The more I study, the more I visit communities, the more I talk to citizens, the more I believe that we're going to need an expansion of a public media system that supports civic engagement, because without it, we're really in dire straits.

Margot, thank you very much. Thanks, Brooke. I really appreciate your time. Margot Suska is the author of Hedged, How Private Investment Funds Helped Destroy American Newspapers and Undermine Democracy. Coming up, as newspapers keep changing hands, the journalists who staff them are caught in the churn. This is On The Media. On The Media.

This episode is brought to you by Progressive Insurance. Whether you love true crime or comedy, celebrity interviews or news, you call the shots on what's in your podcast queue. And guess what? Now you can call them on your auto insurance too with the Name Your Price tool from Progressive. It works just the way it sounds. You tell Progressive how much you want to pay for car insurance and they'll show you coverage options that fit your budget. Get your quote today at Progressive.com to join the over 28 million drivers who trust Progressive.

Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and Affiliates. Price and coverage match limited by state law.

I'm Maria Konnikova. And I'm Nate Silver. And our new podcast, Risky Business, is a show about making better decisions. We're both journalists whom we light as poker players, and that's the lens we're going to use to approach this entire show. We're going to be discussing everything from high-stakes poker to personal questions. Like whether I should call a plumber or fix my shower myself. And of course, we'll be talking about the election, too. Listen to Risky Business wherever you get your podcasts.

This is On The Media. I'm Michael Loewinger. And I'm Brooke Gladstone. So earlier this week, we learned of the purchase of the Baltimore Sun by David Smith, the executive chairman of Sinclair Broadcast Group. The Sun reporting that deal also includes other papers, the Capital Gazette, Carroll County Times and other papers and magazines in the area.

Smith did not disclose how much he paid, but said the deal is independent of the broadcasting company, which does own nearly 200 stations across the U.S. David Smith is known not only for his right-wing broadcasting network Sinclair, but also for his support of conservative causes and groups, including Project Veritas,

Turning Points USA, and Moms for Liberty. Joshua Benton of Neiman Lab described the sale as, quote, an exploration of whether there can be a worse newspaper owner than Alden Global Capital. This week, Smith met with the Sun's staff. Mr. Smith at one point told reporters to go make me some money.

When asked about jobs, Security Smith said, not so reassuringly, that everyone has a job today. The new owner saying at a meeting of the staff that he hadn't read The Sun in 40 years and he found newspapers to be left-wing rags. Milton Kent is a professor of practice in the School of Global Journalism and Communication at Morgan State University. John Oliver did a spectacular takedown a few years ago of how the

the word sort of came down from Sinclair headquarters, which is here in the Baltimore suburbs.

The word came down that they wanted an editorial to be read verbatim on each of its stations across the country. Sinclair can sometimes dictate the content of your local newscast. And in contrast to Fox News, a clearly conservative outlet where you basically know what you're getting, with Sinclair, they are injecting Foxworthy content into the mouths of your local news anchors. Did the FBI have a

personal vendetta in pursuing the Russia investigation of President Trump's former National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn. Did the FBI have a personal vendetta in pursuing the Russia investigation of President Trump's former National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn? Did the FBI have a personal vendetta in pursuing the Russia investigation of President Trump's former National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn? Whether they're in Baltimore, Phoenix, wherever.

That's concerning. Kent started his career at the Baltimore Sun. He even won a full tuition college scholarship from the paper. You could pretty much say that I owe my career to the Baltimore Sun. After graduation, he worked there for over 20 years. What concerns me is that Sinclair seems to have been in for the city of Baltimore. One of their pet ideas is a thing called Project Baltimore.

Where they supposedly expose wrongdoing in the city school system. Baltimore City is the fifth most funded large school system in America. But from this investigation, we analyzed state data and we found a lot of that money is going to educate students who are labeled whereabouts unknown. But the school is still getting the money to educate that child.

And it's a lot. Kent and others found that the project reporting lacked vital context and facts that would have led to a less damning conclusion. I think every school system can stand a bit of scrutiny. But in this case, it seems almost personal. And alarm bells went off for me when I read that the new owner, David Smith, was

said to the staff of The Sun that he thought that Project Baltimore was an ideal model for

A 2018 study by Emory's Gregory J. Martin and Josh McCrane found that stations newly bought by Sinclair cut their coverage of local politics by roughly 10 percent and boosted coverage of national politics by roughly 25 percent. A 2019 study found that Sinclair's political coverage leaned on dramatic rhetoric and partisan sources, effectively pulling viewers to the right. Apparently, Sinclair's political coverage

Apparently, these new Sinclair stations weren't responding to any pent-up demand for conservative local news. On average, they lost viewers when they made these changes. But at no great cost, since national news is so much cheaper to cover than local news. Because one DC-based talking head can serve a hundred markets. Meanwhile, research shows that when local news declines or disappears...

Political corruption increases, along with voter apathy. Journalism professor and former Sun reporter Milton Kent fears the dominance of Sinclair's national agenda could create a devastating ripple effect. In the summertime, when you go pick up a dozen crabs, you lay the newspaper on the table to crack the crabs on. But I think the Sun has meant more to the people of this market, of this city, than just a place to lay your crabs on.

And many of us feared that Alden would shrink the paper down to a husk. I don't think any of us feared that

It would be antagonistic to the city that it's supposed to serve. Well, now they do. In recent years, there's been mounting interest and investment in nonprofit media, a trend scholar Brandt Houston calls the Alden effect. Consider the nonprofit Baltimore Banner, a digital news outlet launched in 2022 in response to Alden's expected pillaging of the Baltimore Sun.

This week, Banner reporters covered The Sun's newest, potentially even more worrying owner, David Smith. Among them, Liz Bui, who before joining the Banner worked for some 30 years at The Sun, starting in 1986. It was a huge, bustling newsroom with seven or eight foreign bureaus, a large Washington staff. We had

eight education reporters at the time, and we were considered a national publication. Later, the Tribune publishing chain, once owner of the LA Times and Newsday, among others, became the Sun's parent company, and Bowie watched as the Sun's staff shrank and shrank at the hands of the Tribune chain's new owner, private equity billionaire Sam Zell. All of the real estate associated with these companies

venerable institutions like the Chicago Tribune and the Baltimore Sun and the Hartford Courant were sold out from under us. And we had to then pay rent to the company. And that money didn't go into supporting the journalism. By the time 2018 rolled around, there were only about 70 journalists left in the newsroom from about 450.

And so it was a much shrunken enterprise. Still, the Baltimore Sun produced great reporting. Bowie was part of the Sun team that won a Pulitzer in 2020, about the same time that Alden came a-callin'. Bowie launched a movement with her union to halt the Sun's sale to the hedge fund called Save Our Sun. I think everybody in the Sun newsroom was terrified when we heard that Alden was buying up the stock.

And I had been speaking over the years with some of the leaders of local foundations who were interested in buying the Sun, as well as Ted Venitoulas, a former politician who had a great deal of interest in the media. I called them all and I said, this is my 911 call. If you guys are really serious about trying to save the paper, you have to do it now because this is who's trying to buy us.

And we started to meet in the early morning in a downtown hotel in secret. We started Save Our Son, and by May, we had collected about 6,000 signatures.

And we sent the petition to the Tribune board and asked them to please vote against Alden. There was a strong local interest in bringing the ownership of the paper back to the city. And of course, they ignored us. But it alerted many people in the community to what was happening. Enter the local hotel entrepreneur and philanthropist,

who fought for the ownership of the son. He tried to purchase the paper as well as the Tribune, the parent company.

Stuart Bainham is a hotelier and former politician, and he began calling people all over the country and saying, how do you run a newspaper? How do you make local news sustainable? And he then said, okay, I'm in, and began negotiating for the sale of the Baltimore Sun. They offered too high a price, and he decided that instead of buying the Sun, he'd buy the Sun's parent company. Right.

just for the sun and then sell off the other papers to local owners in those cities who might be interested. Once he started going after Tribune, then Alden Global Capital came to him and said,

oh, wait, maybe we'll sell you the son. How about we buy Tribune and we will sell you the son? So then there was a tentative deal between Alden and Stuart Bainham. Bainham should have bought the Tribune because in the end, Alden wanted to squeeze him 12 ways from Sunday.

Alden prevailed. Then Stewart began to think about starting his own publication, and he began hiring people. He eventually hired Kimi Yoshino, managing editor at the Los Angeles Times, to run the operation in the fall of 2021. And thus, the Baltimore Banner was born, where you are now a reporter. You've been there since the beginning, as have many of your colleagues from The Sun, and

But weirdly, something happened after Alden gained ownership. Usually hedge funds lay off reporters. But in this case, they offered reasonably generous buyouts and the layoffs never came. The day after the sale went through, Alden offered buyouts to almost everybody in the Tribune Company.

In the case of the Chicago Tribune and many of the other papers, as many as 10% of the people who were offered buyouts took them. At the Baltimore Sun, no one took it. And I think that was because perhaps we'd fought so hard for our newspaper. Why did Alden not slash and burn?

I think that Heath Freeman, who heads Alden Global Capital, and Stuart Bainham were in a very fierce competition, first to get The Sun and then to get Tribune.

And I don't think Alden wanted the Baltimore banner to overtake the sun. There's ego involved here, right? I mean, I'm guessing. So you're saying this was a bleep measuring contest? Yeah. Yeah.

I don't know that for sure, but about 20% of the current staff of the banner came from The Sun. And every one of them was replaced for a long time. It didn't cut into the number of journalists in The Sun newsroom for a while.

Recently, the Sun and the Banner were engaged in an old-style competition for a story involving the Catholic Church. Yes. This spring, when the attorney general released a report about sexual abuse by priests in the church in Maryland, the two news organizations competed to unmask a number of priests.

their names had been redacted. And what happened was the Sun did half of them and the banner did the other half. And so the community benefited from all of this competition, this rise in the number of reporters.

What is really wonderful is the Baltimore Banner has really added a lot of reporters to the media ecosystem in Maryland. And so what you have now is 76 more reporters who are writing different stories, who are writing the same story as The Sun, competing with them.

That means that readers will get their news faster, that the reporters on beats that are competitive will be more aggressive, working way harder because they don't want to get beaten. That

story alone told us what happens when you have good competition and so many more reporters in one city looking at things and looking under rocks. Now, the sun has been purchased from Alden by David Smith, executive chairman of Sinclair. Tell me what you know about Smith and his company, Sinclair. You and your colleagues at the Banner have been reporting on this. We

know that Smith owns 200 television stations, including a Fox station in our area. Many of those stations have a very conservative slant. I think he will insist that there be a more conservative view in his newspaper.

Smith and his stations have been accused of leaning too far and have run afoul of federal regulators. They once racked up a record-breaking $48 million in FCC fines for deceptive practices during an attempted merger with Tribune.

Jared Kushner said in 2016 that the Trump campaign would provide Sinclair stations with extensive access to Trump in exchange for friendly coverage that did not include fact-checking. Smith told Trump in a 2016 meeting, we are here to deliver your message.

We don't know what's going to happen yet with the Baltimore Sun. We don't know how far he will go in interfering in the news gathering. David Smith has bought the Sun independent of Sinclair. So Sinclair does not own the Sun. That is true. But in the past, haven't they worked together to promote each other's material? Yes, they have.

And I think we know that he has a record of doing journalism in Baltimore that I believe does not have context. I've seen journalists working for Fox 45 who leave out very pertinent facts when they report a story. They always...

They often end up being inaccurate in the sense they don't give readers a whole picture of what's actually happening. If the sun did become more like Fox 45, Sinclair Station, how would that alter the media landscape in Maryland? How would it affect how reporters at the Banner do their work?

I am very concerned about this. I worry that there then becomes a sort of a cloud of misinformation that spreads pretty widely, that polarizes our community, that all of the things that have happened with national news start happening on a local level. So that's very concerning. And I think as a reporter, I would have to fight that misinformation in my reporting.

That does seem to be part of the job these days. Is the goodwill of very rich individuals the best hope for local journalism? To some degree, I think it is. Stuart Bainham has definitely given us a big runway, but his philanthropy will end at some point.

So I think you may need a substantial amount of philanthropy to get you off the ground. What we're trying to prove is that once you get started, you can do it alone, sustainable at scale. Stuart Bainham said you

You have to create a large enough organization that the journalism is so compelling that subscribers agree to support it.

So what we are trying to prove is that if you create a big newsroom and a good product, that there's support out there in communities across the nation to sustain it. It makes me feel so hopeful. There's actually still statehouse coverage in the city of Baltimore. It's missing in so many other cities across the country.

Yeah, I've spent a long time in journalism now. I've been a newspaper reporter forever, it seems. And I have never been more excited or committed to what I've been doing. I poured every ounce of myself into trying to save the Baltimore Sun from a hedge fund owner. And it was an emotional roller coaster that I will never forget.

But I am also so hopeful right now. I go to work really excited every day, thinking that we may actually make this work. It's been one of the most joyful times in my life. Liz, thank you so much. Take care. Liz Bowie is an education reporter for The Baltimore Banner. ♪

Coming up, the music criticism business is on the chopping block. This is On The Media. This episode is brought to you by Progressive. Most of you aren't just listening right now. You're driving, cleaning, and even exercising. But what if you could be saving money by switching to Progressive?

Drivers who save by switching save nearly $750 on average, and auto customers qualify for an average of seven discounts. Multitask right now. Quote today at Progressive.com. Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and Affiliates. National average 12-month savings of $744 by new customers surveyed who saved with Progressive between June 2022 and May 2023. Potential savings will vary. Discounts not available in all states and situations.

This is On The Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. And I'm Michael Loewinger. As outlets across the country downsize, change hands, and consolidate, critics have often been among the first to go. After Alden Capital took over the Chicago Tribune in 2021, the paper lost Phil Vettel.

At the time, the city of Chicago's last full-time restaurant reviewer. Late last month, Peter Marks, a respected theater critic at the Washington Post, took a buyout, taking, at least for now, the paper's DC Theater Beat with him. A couple years ago, the Post laid off Pulitzer Prize winner Sarah L. Kaufman, one of the country's few remaining dance critics.

Then there's the world of music writing, which has been bleeding out for years. In October, Bandcamp, a marketplace for independent music and home to a stable of sharp writers, cut half its staff. This week, Conde Nast laid off much of the masthead at Pitchfork, the iconic music publication, and announced the site would merge with men's magazine GQ. In other words, the end of an era.

Started in 1996 by Ryan Schreiber, Pitchfork grew into a unique tastemaker, known for highbrow writing about indie music of the aughts and onward. Ryan Schreiber really stands as an avatar and embodiment of the blog era. Ann Powers is a critic and correspondent for NPR Music. He is a guy who was working in a record store who started this site to publish reviews and publish opinion on music.

music that he loved. And Pitchfork was very associated with indie rock music at that time. The very opinionated reviews, the scoring system that became notorious, where they give a number score to new releases, and that blog-like...

constant stream of content is what made Pitchfork so important and gave Schreiber and his team a chance to make it the influencer that it became. Yeah, and tell me a little bit about some of the bands and genres that were elevated because of Pitchfork, or at least...

were the favorites of the cast of writers in its heyday. Well, Micah, I'm curious, what bands do you associate with Pitchfork? I bet you're a Pitchfork reader. I was a big Pitchfork reader when I was in high school and in college. The bands I associated with it were Spoon or Phoenix or Radiohead, Animal Collective. Broken Social Scene. Yeah, Broken Social Scene. Yep. Arcade Fire would be another one. These are

really the leading quote-unquote indie rock bands of the late 2000s and early 2010s coming out of the indie rock tradition that in previous generations had given us bands ranging from REM to Nirvana. So really Pitchfork was the 21st century flag bearer for the kind of music that Rolling Stone would have covered in the 60s and 70s and Spin Magazine would have covered in the 80s and 90s.

Pitchfork's strong association with that kind of music in the early 2000s is what made it such a potent brand and gave it that foothold that allowed it to truly show its influence. Yeah, and to put even just a finer point on it, there was a 2006 piece in Wired titled The Pitchfork Effect that described the make-or-break power it had over that era of bands. Yeah, let's put this in the historical context of...

music magazines, going back even before the rock era. In the jazz world, for example, you had Downbeat. Its annual polls, its reviews, its articles had the similar effect on the jazz world.

I want to ask you, though, about the style of writing, the voice, because it wasn't just their curation. It was something else about how they wrote. Can you describe it? Well, the basic unit of Pitchfork is the album review. And what is an album review? This is a philosophical question, Micah. What is an album review, Anne? Well, it can be something as small and simple as a little blurb that says, hey, you're going to like this.

or it can be as long as a couple thousand words and really become an essay that considers music in many different contexts. Or possibly it could be a vehicle for personal expression, for memoir, for expressing ideas from a very opinionated place. And I think one of the things that makes Pitchfork so important is that Schreiber and then the other editors there have allowed

to really develop a voice. And sometimes that voice was mean. Yes. Negative reviews, they're kind of like the Thor's hammer of Pitchfork reviews.

You know, writers there and the editors there would wield those negative reviews as a way of proving their influence and a way of generating discussion. Some memorable ones that I've seen writers bring back up in the recent days was its review of Shine On, the Jet album from 2006. This is like a meme, basically. Yeah.

here's this Australian pop rock band that you know is on MTV is kind of generated a lot of buzz in the US Pitchfork gives their album a zero and the review has no text it's just an embedded YouTube video of a monkey peeing into its own mouth right which is funny but like is

Is that criticism? I mean, again, I think we think of Pitchfork as inventing these forms. But if you go back and look at old issues of Rolling Stone from like the 60s and the 70s, they were equally irreverent. This is a side of criticism that's existed since criticism has existed. Some of those zero out of 10 reviews haven't aged so well. Matt LeMay had given Liz Phair's 2003 self-titled album A Zero. At the time, he was a

he, I think, was maybe 18 or 19 and he didn't like that Liz Phair, who was an indie musician, had come out with a more pop radio-friendly album. Right. But then in 2019, LeMay returned to his review and described it as condescending and cringey. He tweeted, quote, the idea that indie rock and radio pop are both cultural constructs,

Language to play with? Masks for an artist to try on? Yeah, I certainly didn't get that. Liz Phair did get that way before many of us did.

Well, kudos to Matt LeMay for engaging in some very constructive self-criticism and kudos to Pitchfork because I think one of the best things that Pitchfork has done in recent years and under the guidance of Pooja Patel, the editor-in-chief who was recently let go as part of these layoffs, is they have revisited old reviews. They have created a whole feature that allowed for them to review records they'd ignored from genres they weren't as interested in. This self-examination and rethinking

confrontation with the limits and problems of the pitchfork approach, to me, that is one of the most inspiring aspects of what's been happening in music writing in the past decade or so. We have a much more diverse field of music writers now. Many more women, many more people of color, many more LGBTQIA people writing about music. And that diversity is

has totally changed what we do. And I think it's great. And Pitchfork has been a huge part of that. Yeah. And you've mentioned that as the publication's aperture has expanded, they now cover a much more varied range of musicians. Like, how has that affected the editorial experience, you think? Yeah. Pitchfork covers pop, but...

But they mostly cover pop and very mainstream artists in their news section. Yes, they will review a Taylor Swift record, for example, and certainly a Beyonce record, as any of us would. They are also covering, you know, very obscure electronic music, avant-garde jazz or avant-garde classical music or Americana music. And I think it's that diversity that makes the reviews section particularly so valuable because it is like going into a great...

huge record store where you could happen upon something you didn't expect. And let's be real, there's so much more to music than the cool new bunch of dudes in tight pants or whatever. Playing some growling guitars. Yeah, I mean, look, I love that stuff. But I think it's great that Pitchfork grew up. And so many of my favorite writers have come through Pitchfork in recent years. They're diversifying the field. And that, to me, is so crucial.

Not everyone has been on board with the changes at the site. Writing in The Guardian this week, Laura Snapes responded to critics of Pitchfork who have, quote, lamented Pitchfork's poptimist shift over the past decade. Poptimists. What is she referring to there? Well, I'm glad you brought up that term, Micah, because it's one that drives me crazy.

So the word poptimism originated in response to an essay that Califasane wrote in the New York Times called The Rap Against Rockism. And Califas' criticism of the world of music writing was that it was dominated by straight white men who liked guitar-based rock music made by straight white men, and that this had created a hierarchy within the music industry.

But quickly, this critique created a space for some of us to say, hey, let's also take mainstream pop music seriously. Let's take dance music seriously. Let's take these fields that happen to be dominated by African-American artists, by women. Let's make a space for that. Carl Wilson also wrote a really important book.

It was about Celine Dion, but it was really about how our tastes form. Oh, yes. This is Journey to the End of Taste. Is that what it is? Yeah. It's a fascinating premise. He basically says, Celine Dion, one of the best-selling artists of our time. I hate her music. Right. Why? Why?

And, you know, he was saying, okay, from my standpoint as a fan of indie rock, as a white guy, et cetera, what am I bringing to the table when I listen to a Celine Dion record? Why do I think this is quote-unquote bad music? Why do so many other people think it's great music? And that's the essence of what the Poptimus Project really was. It was not to promote mainstream music. It was to take seriously pop.

Music that is very popular, music that rock critics scorned historically. I think Pitchfork's evolution from a site that sort of embodied that scorn to one that was fighting against it was one of the most beautiful things that's happened in media in the past few decades.

And it's been interesting to see the evolution of Pitchfork land between all of these competing interests. I'm thinking of the 2020 review of Taylor Swift's surprise indie folk album, Folklore, written by Jillian Mapes.

who wrote a pretty positive review of the album, but ultimately the site only gave the album an eight. And she was sent death threats, constant harassment online. And, you know, Jill was one of the people who was laid off this week.

a terrible loss to the publication, and some fans were attacking her even now. What can I say? I've gone through this myself. I published a piece on Lana Del Rey on one of her albums that insufficiently praised her or that she misunderstood, and I went through a lot of online harassment for years, I have to say, after that review.

This is truly something that does plague critics, reporters, media commentators now. Organized

by fans. It's something we have to live with, and sometimes it goes to horrible extremes. But that's a separate issue, in my view, than whether or not poptimism is a valuable or even sustainable way of doing criticism. It's just fascinating to me that on one hand, you have people who bristle at the very fact that Pitchfork is reviewing Taylor Swift. Right. And on the other...

Fans of Taylor Swift aren't happy with the critical review about her. The critic has always been an embattled figure in our society, both revered and utterly disrespected, both considered a nothing who only lives through the works of others and

and, you know, someone that supposedly makes people tremble when they walk in the room, right? In a strange way, the critic is in a parallel relationship with the musician who also is revered and scorned in our society, you know? All of this says something about how we treat culture. On the one hand...

There are these attempts to sportsify it, to quantify it, to make hierarchies, which always inevitably fail because encounters with art are personal. But on the other hand, there is such a thing as aesthetic judgment.

There is some value in saying Stevie Wonder is one of the greatest artists who ever lived. And this is why. Because he could write amazing melodies, because he was one of the most technologically advanced musicians of his time, because he was both funky and sweet and comical.

cutting in his greatest songs all at the same time. But that's an aesthetic judgment as well as a personal one. And I think that that combination of stepping back and being close at the same time, it's a complicated way to talk about culture and it can be upsetting to some.

Honestly, just hearing you speak right now makes the case for why cultural criticism needs to exist. Well, thank you. But the fact is, with this alarming downsizing at Pitchfork, coupled with recent layoffs at Bandcamp, another site that helps support independent musicians, that also hosted very, very smart, interesting writing about all kinds of music, much of it below the radar,

It's hard not to feel that this criticism and its home on the internet is shrinking. Amanda Petrusich, who's a music critic at The New Yorker, wrote on X slash Twitter that the Pitchfork News was, quote, a death knell for the record review. Is this the end of music reviews as we understand it? The considered encounter between a devoted, intelligent listener who is also an excellent writer,

and a work of art. That will live on forever because what a review does is it creates space for a reader to have an encounter with a work that is guided by the encounter that the critic had. And it guides you into a wider understanding. Maybe it's going to make you think about how the

The Boy Genius record reflects attitudes about friendship in the 21st century. Maybe the reviewer can point out something that was just on the tip of your own tongue. Then you have that aha moment. And that's what the beauty is of a review, is walking into the space of appreciating and loving art with a kind and thoughtful guide. And maybe...

Maybe a kind of cruel guy who can say, yeah, this is BS, you know. But that role, I think we still want. What form it takes as media changes, I can't predict. But I still think people want that time and space to think and feel with another person who also loves the art they love. Anne, thanks so much. It was great talking to you.

Ann Powers is a critic and correspondent for NPR Music. She's the author of several books, including the forthcoming biography, Traveling on the Path of Joni Mitchell, which comes out in June. ♪

That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Eloise Blondio, Molly Rosen, Rebecca Clark-Calendar, and Candice Wong, with help from Sean Merchant. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Andrew Nerviano and Brendan Dalton. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone. And I'm Michael Loewinger.