Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

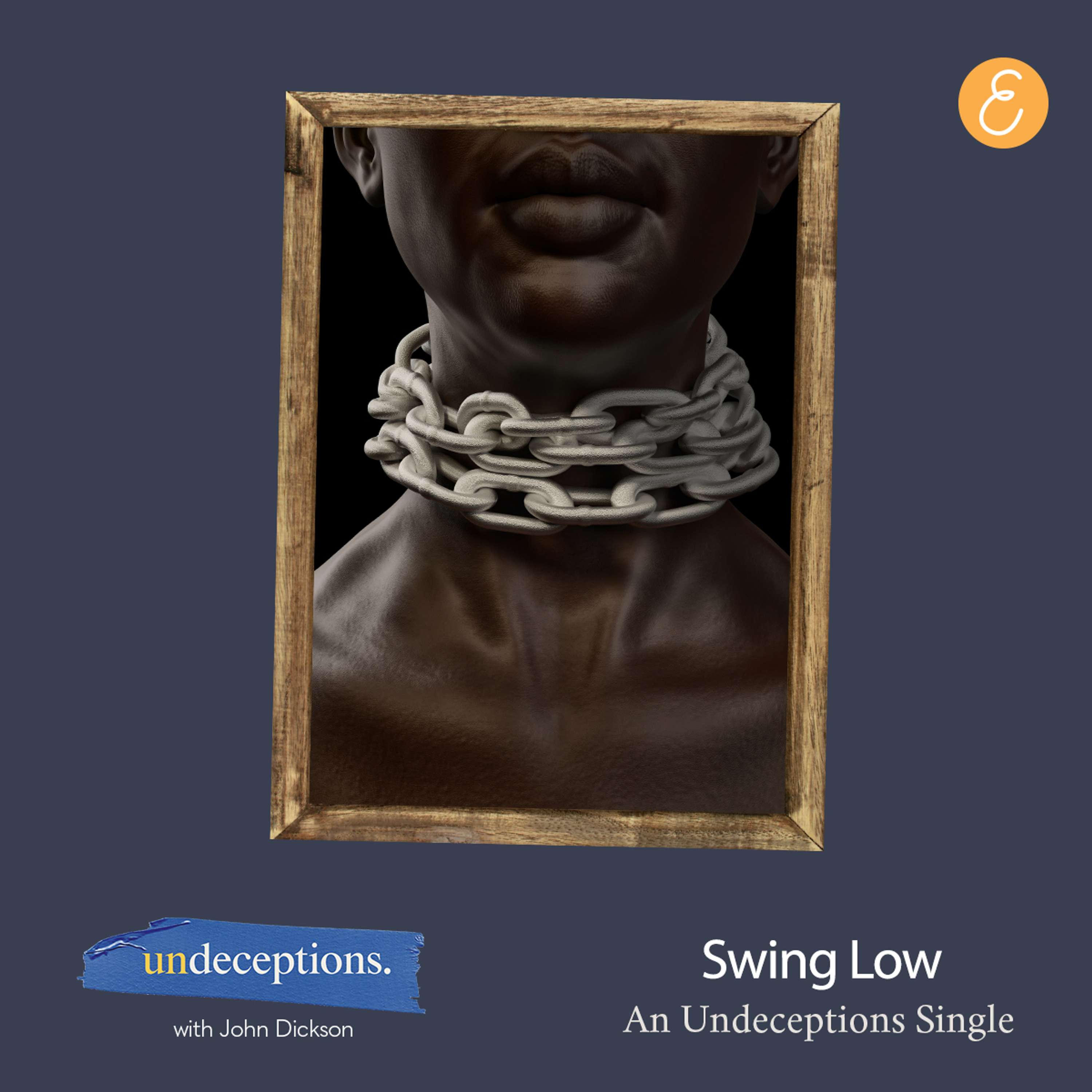

Hi, John Dixon with an Undeceptions single. It's often pointed out that the leaders of the abolition movements of the 18th and 19th centuries were very often outspoken Christians with overtly religious arguments.

In Britain, for example, it was people like Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce. In the US, people like William Lloyd Garrison, who was the founder of the influential abolitionist magazine, The Liberator. Or the amazing rhetorician and former slave, Frederick Douglass. If you've never read any of his speeches, please go and do so. Abolitionism was not a secular movement.

Professor Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, recently said, "If the abolition of slavery had been left to enlightened secularists in the 18th century, we would still be waiting." Now, that may be a little too harsh, but he has a point.

It's a mistake to imagine that the push to end slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries was a secular project rather than a religious one. There was religion on both sides, definitely. The difference is the arguments against slavery were almost entirely religious or quasi-religious. But the arguments for slavery were a combination of arguments, economic, scientific,

pragmatic as well as religious rationales. By the way, the scientific arguments for the subjugation of Africans in the 19th century went way beyond any supposed biblical argument.

I mean, many Christians may have argued that the Bible permits slavery, but they didn't claim Africans were sub-human. For that, you needed the science of the day.

And if you're in any doubt about that, let me recommend you try and track down the 1863 pamphlet by James Hunt. It's titled, I'm sorry to read this out, On the Negro's Place in Nature. And it was published by the London Anthropological Society. James Hunt was in fact the president of the society. The pamphlet is a full-throated scientific argument

that Africans are a different, lower track of the human species. Anyway, the preeminent American authority on the history of slavery is David Bryan Davis at Yale University. He titled his major book on the subject, In the Image of God, Religion, Moral Values, and Our Heritage. In this book, he insists that, quote,

The popular hostility to slavery that emerged almost simultaneously in England and in parts of the United States drew on traditions of natural law and a revivified sense of the image of God in man.

The doctrine of the image of God, obviously, is a totally biblical Christian thing. But actually, so is the natural law tradition that Davis mentions here. He's not referring to the ancient Greek tradition of natural law. I mean, that tradition absolutely said that nature intended a slave class.

Davis means the natural law tradition of British and American free thinkers in this period, who basically inherited the notion of the image of God in every human being, but then desacralized it. It was still essentially a religious outlook because it was premised on the idea that God, the creator, some vague creator, still made everyone equal.

The classic statement of this natural law tradition was in the Declaration of Independence: "All men are created equal and are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights." Anyway, my point:

is that someone like Frederick Douglass, himself a former slave, was scathing about churches that supported slavery. And there were many, especially in the South. In his public lectures on both sides of the Atlantic, he called these churches the "Ballwalk of American Slavery".

He said slave-supporting churches were especially culpable, partly because they provided moral cover for an evil economic system, and partly because they were betraying their own core doctrine that God loves all those, quote, stamped with the likeness of the eternal God, as Douglass put it in a letter to William Lloyd Garrison.

It's clear from his speeches that he believed he was calling slave churches not forward to a new vision of life, but back to their foundational doctrine that all men and women share a common creator and deserve filial love and respect. Douglass and others said that Christian tolerance of slavery was an inexcusable blind spot for many Christians.

but they didn't for a second think that slavery was an outcome of Christianity, which is how I think some people today see it. So let me try and settle this in a more ancient context. It's true that the New Testament nowhere tells Christians to put an end to slavery. Historically, this is a lamentable fact, and maybe it's something I'll raise with the Lord one day.

But the New Testament does explicitly condemn slave traders as unholy and profane and contrary to the gospel. That's 1 Timothy 1. It also urges slaves to gain their freedom if they're able. That's 1 Corinthians 7. And it insists that no one should choose to become a slave. 1 Corinthians 7 also. By the way, people did sometimes choose slavery for economic reasons. And Paul forbade that.

Almost unbelievably, we have very early evidence from just after the New Testament, so about the year 96, that Christians sometimes did sell themselves into slavery in order to donate the sale price to the poor. I kid you not.

Christians in the second and third centuries started to take really innovative measures to moderate slavery from within. They didn't imagine that they could remove it, but they thought they could change it.

And so by the year 115, churches had started to establish dedicated funds to pay for the manumission, the formal release of slaves. This ministry grew to become a massive part of Christian charity in the first few centuries.

And it was partly in recognition of this that Emperor Constantine, when he became Christian, gave bishops the authority to manumit slaves at church expense in a decree of 18th April 321. This then bestowed on a former slave the full rights of Roman citizenship. And Christians used this in tens of thousands of cases. Sadly, things rarely went further.

Christians didn't overthrow slavery in the ancient world, even when theoretically they might have had the power to do so from about the 6th century. Although in the next couple of weeks I'll offer another one of these singles about an incredible slave-freeing movement in the Middle Ages that hardly anyone knows about but is quite extraordinary.

The absence of any clear New Testament command to abolish slavery, combined with the ubiquity of the system throughout Roman and barbarian society, meant that most Christians in most parts of the world just accepted slavery as an unfortunate necessity in a fallen world.

Rowan Williams is probably right to say that Christianity was able to light, quote, a long fuse of argument and discovery about slavery, which eventually explodes in the 18th and 19th centuries. But we can all agree that

That fuse was too long. It all leaves me wondering, what are my blind spots? When I think of Christians and slavery, or secularists and slavery for that matter, I don't just feel shame and outrage. I feel nervous about myself, about my culture.

What are the long fuses of discovery that are still yet to explode and expose us of evil blind spots? Of course, I've got no idea. They're in my blind spot. See ya. You've been listening to the Eternity Podcast Network.