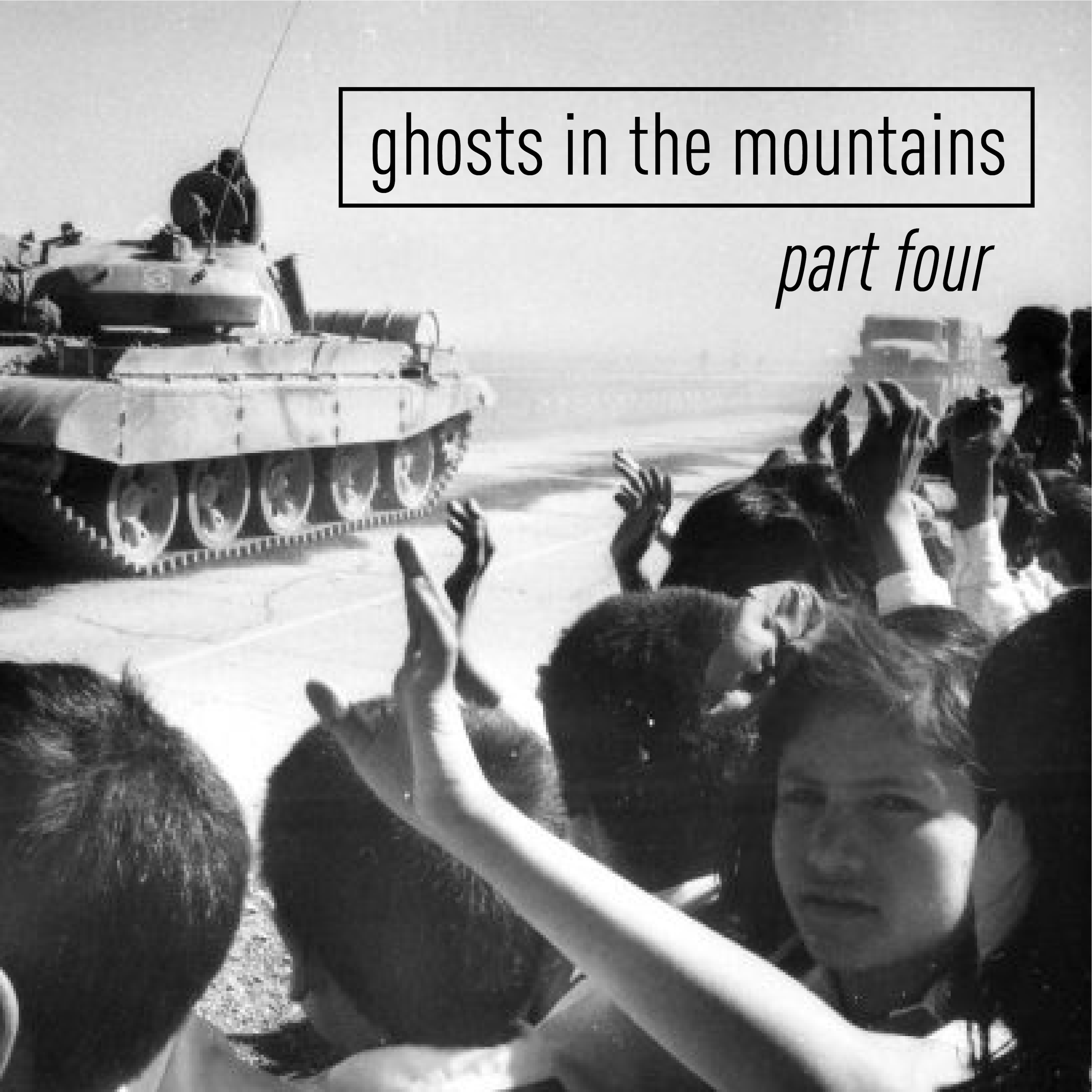

Ghosts in the Mountains: The Mujahideen Civil War (Part 4)

Conflicted: A History Podcast

Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

Hello and welcome to Conflicted, the history podcast where we talk about the struggles that shaped us, the tough questions that they pose, and why we should care about any of it. Conflicted is a member of the Evergreen Podcast Network, and as always, I'm your host, Zach Cornwell. You are listening to the fourth and final episode of a limited series on the Soviet-Afghan War and the fallout that it triggered.

Today's episode is about the fallout. Now, you might have noticed upon clicking or tapping on this episode that the naming structure is slightly different this time around. The series name is still Ghosts in the Mountains, but rather than subtitle it The Soviet-Afghan War Part 4, I decided to subtitle it The Mujahideen Civil War. Because at this point in the story, the Soviet-Afghan War is...

over. The Russians are gone, and it didn't feel quite right to extend that title to this installment. Now, it goes without saying, if you haven't listened to parts 1, 2, and 3 of the series, definitely go ahead and do that. A lot of important characters and events from part 3 are going to be carrying over to this episode, so without that context, you might be scratching your head a little bit. But for everybody who's caught up, let's remind ourselves of where we've been, so we can jump into the next phase of our story, clear-eyed

and confident. When we left off last time, the Soviet 40th Army was finally leaving Afghanistan after 10 long, miserable years. On February 15th, 1989, the last Soviet soldiers crossed the Friendship Bridge and said do svidaniya to the Ghost in the Mountains, the

the Mujahideen. But the Soviets were leaving some ghosts of their own behind in those valleys and ravines. Ghosts of friends, ghosts of allies, ghosts of the men that they had once been, or might have been. Afghanistan in 1989 was very, very different from Afghanistan in 1979. After a decade of atrocity and upheaval, the Soviets were leaving behind a country that was essentially haunted.

Everywhere you looked, you saw reminders of the war. The empty huts and crumbling buildings, the rusted carcasses of Soviet gunships, the deadly constellations of anti-personnel mines, all but invisible beneath a thin layer of dust and sand. The Soviets had lost the war...

and lost hard. And the self-described architects of that humiliating defeat were gloating from thousands of miles away in Langley, Virginia. Last episode, we spent a good chunk of time talking about the American role in the war, specifically the efforts of the Central Intelligence Agency, the CIA.

We talked about how the CIA used every dollar and dime at their disposal to arm, train, fund, and organize the Mujahideen guerrillas in hope of giving Mother Russia its very own Vietnam. And in the eyes of the American intelligence community, that objective had been achieved.

As the 40th Army lumbered back across the French ship bridge, bottles were popping from Pakistan to the Pentagon. The CIA's costly, covert war seemed fully vindicated two years later, in 1991, when the Soviet Union itself dissolved completely. Mikhail Gorbachev's efforts to adapt his country to the future, valiant and well-intentioned as they might have been, had ultimately failed.

The USSR was Donsky. In an outpouring of relief and emotion, the international community exhaled the breath that it had been anxiously holding since the two superpowers had emerged from the rubble of World War II in 1945.

The Cold War was finally over. That same year, in 1991, when former CIA station chief in Islamabad, Milton Bearden, mentioned Afghanistan in passing to the then-U.S. President George H.W. Bush, Bush asked, quote, Is that thing still going on?

End quote. Well, yes, Mr. President, that thing was still going on. Because in Afghanistan, the war was far from over. Last time, in part three, we spent a lot of time getting to know two very important people in the Mujahideen movement, Ahmed Shah Massoud and Gulbadin Hekmatyar. Massoud and Hekmatyar were two of the most talented, influential, and famous Mujahideen commanders to emerge from the jihad against the Soviets. They

They had each poured every ounce of energy, body and soul into pushing the 40th Army out of Afghanistan. But although their basic goals were similar, they could not have been more different. And as the Soviets left Afghanistan, Massoud and Hekmatyar found themselves on a collision course that would decide the future of their country. So, let's remind ourselves, who are these guys again? And who are they at this time, circa the early 90s?

In the left corner, you have Ahmed Shah Massoud, the Lion of the Panjshir, loved by his men, adored by Western media, devout, honorable, and kind, but riddled with personal doubts and prone to self-criticism.

Still, he is hailed as a military genius, having protected his home turf in the Panjshir Valley against nine massive Soviet offensives. Some people have started calling him the "Afghan Napoleon." Many people believe and hope that Ahmad Shah Massoud will be the man to step in and fill the power vacuum in Afghanistan. He is a moderate, inclusive Afghan nationalist who wants to build a nation free of foreign influence, whether it be America, Russia, Pakistan, or anyone else.

In the right corner, you have Gulbadin Hekmatyar, the Dark Prince, as some CIA elders melodramatically call him. Hekmatyar believes that he, and he alone, is the future of Afghanistan. His pragmatic, pitiless intellect is matched only by his fiery fundamentalism. He hates Soviets and Americans in equal measure, but has accepted hundreds of millions from the CIA to strengthen his position. In truth, his cynical partnership with the CIA is just a means to an end.

On his preordained path to power, there is no one he will not torture or betray or have killed. To Hekmatyar, human life is just like any other resource. Like bullets or bombs, it has to be expended and used to reach the ultimate goal. And nothing will stand in his way, especially not Ahmed Shah Massoud. Last episode, we traced the relationship between these two men across the decades, beginning in the early 1970s.

They'd first met as young 20-something college students in Kabul University, student activists and members of the controversial Muslim youth organization. And although they both shared a distrust of communism and Soviet imperialism, their visions sharply diverged almost immediately. Massoud thought Hekmatyar was way too extreme, an uncompromising fanatic, a lunatic who allegedly threw acid in the faces of young women who wore revealing Western clothes.

Hekmatyar thought Massoud wasn't nearly extreme enough, a coward who didn't have the stomach to help ignite a transnational Islamist revolution and literally save the world. Each felt that the other was a bad Muslim, and their animosity evolved into a bitter, lifelong rivalry. Throughout the course of the Soviet-Afghan war, Massoud and Hekmatyar's rival Mujahideen forces had bickered and brawled,

nibbling and skirmishing at the peripheries of each other's territory, smacking at each other with one hand while fending off the 40th Army with the other. But now that the Soviets were gone, Hekmatyar and Massoud were free to turn their attention towards the unprotected prize of

of Kabul. The Afghan communist government was wobbling like a very tall Jenga tower and all that was left to do was deliver the final push. And if they were able to settle old scores along the way, so be it. The stage was set for a Shakespearean showdown in the very place the two men had first met

all those years ago. In today's episode, broadly speaking, we're going to look at what happened to Afghanistan when the Soviets pulled out and the world lost interest. For many people at the time, Afghanistan was only important for as long as the Soviet Union was in it. Without the presence of a global superpower, Afghanistan was just another backward little country destined to sit on the sidelines of history. But we, with our 2020 hindsight goggles, know that that is not the case.

Massoud and Hekmatyar's looming civil war, combined with ongoing, constant meddling from Pakistan and the CIA, destroyed Afghanistan...

Once and for all. After 10 years of Soviet occupation, any hope of a free and prosperous Afghanistan was already on life support. The Mujahideen civil war succeeded in pulling the plug. And once the nation flatlined, something new was born in its place. The corpse of Afghanistan became an incubator for an ideology and a worldview even more extreme than Golbat and Hekmatyar's. The world was about to be introduced to the Taliban.

for the very first time. Now, it's been a long road to get to the end of our story and I'm very excited to hopefully, inshallah, stick the landing and reward your patience with a finale worthy of your attention. As always, I know how valuable your time is and I appreciate you spending some of it with me. So, with all that said, let's get started. Welcome to Ghosts in the Mountains Part 4, The Mujahideen Civil War.

It's April 16th, 1992. We're in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. It's the middle of the night, about 1:45 AM,

and a car is racing towards the airport as fast as it can go. Sitting in the back seat is a very nervous 45-year-old man named Dr. Najibullah. That's N-A-J-I-B-U-L-L-A-H. Dr. Najibullah is the last communist leader of Afghanistan, and on April 16th, 1992, he is running for his life.

He's trying to get to the airport so he can get on a plane and get the hell out of Kabul. Because the Mujahideen are on their way. Dr. Najibullah is a brand new addition to our cast of characters. We have not met him before, but his story is a fascinating one nonetheless. Najibullah was a massive bruiser of a guy. He was built like a weightlifter, and people called him "The Ox."

His muscles would visibly strain against the sleeves of his pinstripe suit, like sausages trying to bust out of their casing. Basically, he was a huge, intimidating guy, which came in handy in his line of work. Najibullah got his first big break in the Afghan communist government as the chief of its secret police force.

essentially Afghanistan's KGB. It was a nasty job in which nasty people did nasty work. The Afghan secret police spent the majority of the early 1980s implementing their own miniature reign of terror on the urban population of Afghanistan. They arrested anyone and everyone who was a suspected enemy of the deeply unpopular Soviet-sponsored regime. Anyone who might be giving aid or support or information to the Mujahideen guerrillas. And it was not hard to wind up on one of their lists.

If you were unfortunate enough to be hauled away to one of their detention centers, you may have found yourself cowering in the shadow of the hulking Dr. Najibullah. As a dedicated, hardcore communist, Najibullah genuinely believed in what the Soviets were doing in Afghanistan. And consequently, he despised the Mujahideen with an unnerving intensity.

On one occasion, the secret police captured a high-profile Mujahideen guerrilla and brought him to Najibullah. The ox raised his massive fist and knocked the man's two front teeth out with a single punch. In a final twist of the knife, he leaned down and mocked the man's faith in God. Quote, "...I was looking for you in the sky, but found you here on earth."

End quote. Getting a little improvised dentistry from the ox was the least of your worries in one of Najibullah's detention centers. Torture was like a higher calling for the good doctor. He had an uncommon aptitude for it.

As historians Chris Sands and Faisal Minnala Kazizai write, there were, quote, two traits central to his character, acumen and cruelty, end quote. Under Najibullah's direction, inmates had their fingernails torn out, drill bits inserted into their thigh bones, and their beards set on fire. Electrocution and creative placement of bottles and red-hot kebab skewers were also some of the secret police's go-to methods. In

In his tenure as Afghanistan's torturer-in-chief, Najibullah did everything he could to smoke the Mujahideen out of their holes. He turned kids against their parents, husbands against wives, brothers against brothers. He bribed and blackmailed, murdered and maimed. He skipped meals and slept just four hours a night in his single-minded pursuit of criminalization.

of crushing the Mujahideen insurgency. Well, eventually, through those robust efforts, Najibullah caught the eye of the KGB. They were always on the lookout for promising up-and-comers and they were very impressed with his brutal methodology. So, when the Kremlin decided it needed a fresh new face to lead the Afghan communist puppet regime in 1986, Dr. Najibullah got the call. He became Moscow's new favorite Afghan. Dr. Najibullah became President Najibullah.

But statecraft posed a novel challenge for Najibullah. Bones could be bent and broken with ease, but shaping a complex political situation to your preferences, well, that was another matter entirely. Shortly after Dr. Najibullah was given the top job in the Afghan government and was allowed into the Soviet circle of trust, he was

He learned something very, very distressing. The Soviets were seriously considering pulling the 40th Army out of Afghanistan, while all of a sudden, Dr. Najibullah began to feel like the guy who'd bought the very last ticket on the Titanic. His exciting, upward career mobility had curdled into a curse. The Soviet 40th Army was the only thing holding back the Mujahideen, like a paper-thin dam guarding against a churning, implacable river. And

And if the Soviets pulled out for good, Kabul would eventually, inevitably fall. When that happened, Najibullah would be left holding the bag, and the ox might find himself carved up like a sacrificial bull by the vengeful guerrillas.

But Moscow had a plan. There were sophisticated and sympathetic Soviet politicians in Najibullah's corner, people who did not want to leave the puppet government high and dry at the mercy of the Mujahideen. To ensure the survival of the Afghan communist regime, Najibullah was encouraged to extend an olive branch to the Mujahideen.

The Soviets said, "Listen man, if you want to survive after we're gone, you gotta make inroads with these people. Maybe if you throw them a bone, make a few changes here and there, a compromise can be made and you can stay in power." The cognitive dissonance for Naji Bulla must have been unimaginable. He had spent the better part of his 30s detaining, torturing, and murdering these people, and now Moscow is telling him to somehow mend those fences.

to make a deal, as he saw it, with fanatics. But the noose was getting tighter day by day and Najibullah's self-preservation instincts were as well developed as his muscular physique. So, to his credit, he threw himself into the task. But as it turns out, building bridges is a lot harder than breaking fingers. As Mir Tamim Ansari writes, quote,

He really did. He tried everything he could. He changed the name of KHAD to WAD, but everybody knew it was the same old dreaded secret police. He renamed the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan to the Fatherland Party, but no one started singing patriotic anthems. He had a new constitution written, declaring Afghanistan an Islamic Republic and guaranteeing the freedom of all citizens.

but no one believed him. He started building mosques and religious schools, he called for national reconciliation, he offered cabinet positions to selected mujahideen leaders, he even offered to step down if certain conditions were met. The plan might have worked, ten years earlier, but in the late 80s too much blood had

had flowed under the bridge. End quote. By 1988, Mikhail Gorbachev had made it crystal clear to the entire world that the Soviets were getting the hell out of Afghanistan. But he assured Najibullah that financial aid would continue to flow into Kabul even if Soviet gunships and tanks and soldiers could not.

The Americans were still funding the Mujahideen, so the Soviet Union would continue funding Najibullah, something to the tune of $3 billion a year, even after the 40th Army was long gone. The Aks would, in theory, have a fighting chance against the Mujahideen. As long as the Soviet Union was around, Najibullah was assured, he could count on their ongoing support. Everything was going to be just fine. Well, those hopes came crashing down in 1991, when the Soviet Union finally, officially,

collapsed. As one historian poetically put it, "...freed from the shackles of the Afghan war, the Soviet Union careened towards oblivion." With sobering clarity, the Ox realized what that meant for Afghanistan in general, and for him in particular. No more money, no more weapons, no more advice or support or help. He was truly on his own, stranded and surrounded.

As the Mujahideen forces tightened like a hand around the throat of Kabul, Dr. Najibullah dug in for an ugly, last-ditch defense. Even his wife was defiant, saying, quote, We would prefer to be killed on the doorsteps of this house rather than die in the eyes of our people by choosing the path of flight from their bitter misfortune. We will stay with them here to the end, whether it be happy or bitter. End quote.

But Najibullah and his army were not facing the disorganized country bumpkins that had taken poorly aimed potshots at Soviet tanks more than a decade earlier in 1979. By 1991, the seven Mujahideen factions, Masud and Hekmatyars included, were fielding extremely well-trained, well-armed, well-coordinated armies and militias.

These were not the same rough-and-tumble guerrillas that Jan Goodwin from Ladies Home Journal had traveled with back in 1985. They were not fighting with rusty grenades and breech-loading rifles anymore. Ten years of heavy, sustained financial aid from shadow contributors like the CIA in Saudi Arabia had transformed the Mujahideen into a terrifying and modern military foe.

They had helicopters, fighter jets, and rockets. They had sophisticated communications equipment. They could conduct targeted and precise airstrikes. The CIA had even refurbished Iraqi tanks captured in the Gulf War and smuggled them into Pakistan for the ISI to transfer to the guerrillas. The most effective weapon in the Mujahideen's arsenal, of course, had always been their faith, the inexhaustible motivation to keep fighting, to keep conducting their jihad against the Soviets and the puppet government.

But now, they had all the weapons that they could ever need to make their goals a reality. As Steve Cole writes, quote, By 1992, there were more personal weapons in Afghanistan than in India and Pakistan combined.

End quote. Now to just put that in perspective real quick, in 1992, India's population was 900 million people, Pakistan's was 113 million, and Afghanistan's was just shy of 15 million. Against such highly motivated, weapons-rich, and cash-flush adversaries like the Mujahideen, Najibullah and his goons never

never stood a chance. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Najibullah's Afghan government managed to resist the Mujahideen for about a year. But it wasn't enough. As Mir Tamim Ansari writes, "...Najibullah fought like a dog, but he couldn't keep the wolves at bay."

The fate of the Afghan communist regime was sealed when a key ally of Najibullah's government defected to the Mujahideen and took all of his men with him. By spring of 1992, there was no one left willing to raise a hand in defense of the regime. As Kabul's defenses crumbled like wet tissue paper and Mujahideen forces started creeping into the outskirts of the city, Najibullah realized his time was up. It was time to get the hell out of Dodge.

As his chauffeured car sped towards the Kabul airport in the middle of the night on April 16th, 1992, Najibullah tried not to panic. The ox knew all about fear. He had seen it, savored it, in the faces of more men than he could count in the torture chambers and black sites during his secret police days. And if Najibullah found any irony in the fact that he was now the one being hunted, running scared through the streets of Kabul, he kept it to himself.

But there was a flicker of light at the end of the tunnel. The United Nations had agreed to evacuate Najibullah and his family out of Afghanistan and relocate them to India. All he had to do was make it to the runway, step on the plane, and his new life could begin. A little after 2 o'clock in the morning, Najibullah's car pulled up to the checkpoint, which granted entry into the airport. It was surrounded by armed men with machine guns. The

The officer in charge demanded a password from Najibullah's driver. The driver answered with the password he had been given, but the officer just shook his head. Sorry buddy, wrong password. Initially, Najibullah assumed that it was a simple mistake. Some idiot on guard duty who didn't realize that he was dealing with the most important man in the city. Najibullah poked his head out of the backseat window and yelled at the guards, quote, Let us through, you asshole. Everything has been arranged. And

End quote. But the airport guards wouldn't budge. They didn't answer to Najibullah or his crumbling government. These soldiers belonged to an Uzbek militia that had been bought and paid for by the Mujahideen. Their orders were to turn anyone and everyone, especially the president of Afghanistan, away from the airport. Kabul was locked down, and Najibullah watched his escape hatch slam shut right in front of his face. In a panic, he told the driver to hang a U-turn and

and head to the only safe place left in the entire city, the United Nations compound. Najibullah leapt out of the car and practically sprinted inside the United Nations building. The president of Afghanistan was essentially a kid putting his hand on a tree in a game of tag and claiming safe. All he could do now was sit tight.

and hoped that when the Mujahideen leadership finally entered the city, they respected his legal asylum. And with that, my friends, the last vestige of Afghanistan's short-lived communist government, the regime that had provoked an insurgency, plunged the country into civil war, and invited a foreign army onto its soil to murder and displace millions of its own people, was gone. As the sun rose over Kabul on April 17th, 1992, the inhabitants of the city might have looked out of their windows with the slimmest feeling ever.

Najibullah was in hiding. The Soviets were gone. Maybe now, finally, there might be a chance for some semblance of peace. But what they did not know was that their nightmare was only beginning.

I'm Ken Harbaugh, host of Burn the Boats from Evergreen Podcasts. I interview political leaders and influencers, folks like award-winning journalist Soledad O'Brien and conservative columnist Bill Kristol about the choices they confront when failure is not an option. I won't agree with everyone I talk to, but I respect anyone who believes in something enough to risk everything for it. Because history belongs to those willing to burn the boats. Episodes are out every other week, wherever you get your podcasts.

When Gulbadin Hekmatyar was a young man, in his mid-twenties or so, he had a dream. It was a very vivid dream, and the memory of it stuck with him for years and years afterwards. In the dream, Hekmatyar was floating, adrift, in a cloudless night sky. Above him, he could see a dazzling canopy of stars.

But they weren't the small little pinpricks we look up at and see in real life. They were bright, blazing celestial objects. And as he looked at them, the stars began moving from east to west, moving faster and faster, streaking like tracer fire against the blackness. As they traveled across the sky, the stars began to transform and change shape. Initially, they looked like hats or turbans. But the more they changed, the more they started to resemble crowns.

As one of these crowns made of pure starlight traveled across the sky, Hekmatyar reached out with his hand and plucked it out of the air. Then he put the crown on his head, and after that, he woke up.

Dreams held a lot of significance for Hekmatyar. In his time, the Prophet Muhammad was said to have experienced dreams and visions that told the future or gave insight into the present. Hekmatyar took these Quranic anecdotes literally, and so when he had a particularly crazy dream, he dissected every detail of it, tried to divine what it really meant. But this new dream was especially impactful. Floating in the sky, the stars moving from east to west,

the crown of pure light that settled on his head. At first, Hekmatyar thought that this meant that he would be the patriarch of a large family, the crown symbolizing his status as a father, and the other crown symbolizing the many sons that he would have. But as he thought about it more and more,

He began to believe that God had sent him this prophetic dream to show him that great things lay in his future. Hekmatyar was a deeply ambitious person and he understood his own unquenchable aspirations through the lens of destiny and prophecy. The starlight crown was a literal crown. Someday, Hekmatyar would rule over Afghanistan as its undisputed ruler. And the other stars moving from east to west?

Those symbolized the Mujahideen fighters and the trajectory that their jihad must eventually take. Looking west from Peshawar, across the Afghan border, beyond to Europe, and beyond that, America.

On April 17, 1992, while President Najibullah cowered in the UN compound in downtown Kabul, Hekmatyar's Mujahideen forces massed a few miles south of the capital. It had been almost 20 years since Hekmatyar had laid eyes on Kabul. Last time he'd been there, he'd been a fiery young radical, barely 25 years old, with a thick black beard and a target on his back.

His activities in the Muslim youth had branded him an enemy of the state, and he'd had to flee to Pakistan. But a lot had changed since those early days. Fast forward to 1992, Gulbad-in-Heqmachar was 43 years old,

And he was not a two-bit student activist anymore. By the early 1990s, Hekmatyar's Mujahideen faction had developed into an extremely powerful military and political force inside Afghanistan. As Chris Sands and Faisal Manala Kazizai put it, Hekmatyar's operation was a cross between, quote, "...an army, a government, a religious movement, and a lucrative criminal enterprise."

End quote. Mountains of cash from CIA spooks, Saudi sheiks, and Pakistani generals were supplemented by money made from engaging in the international heroin trade. Afghanistan is home to some of the largest crops of opium poppies in the world, and Hekmatyar's faction was able to take control of many of these labs and get a slice of those sweet, sweet profits.

The drug trade was big business in Afghanistan, and if there was extra money to be made to finance his bid for ultimate power, Hekmatyar wasn't going to pass that opportunity up. As Steve Cole writes, quote, By the early 1990s, Afghanistan rivaled Colombia and Burma as a fountainhead of global heroin supply. End quote.

As his army closed in on Kabul from the south, Hekmatyar was one of the most influential and admired Islamist revolutionaries in the world. He had mentored up-and-coming radicals all across the Middle East, from Cairo to Riyadh. He spent his time writing poetry, denouncing rivals, and formulating battle plans.

He taught himself to read Arabic. He eventually learned computer programming. Hekmatyar never stopped being a student, even when he was the undisputed master of his Mujahideen faction. He was a preacher, a kingpin, and a warlord all wrapped up in one. If he saw any ethical contradictions in that unique cocktail of roles, they didn't trouble him in the slightest. As his CIA-supplied tanks from Iraq rumbled to the outskirts of Kabul, Hekmatyar was so close to his goal,

He could taste it. He must have been thinking about what would come next. And believe me, he was dreaming very, very big. Once his Mujahideen infiltrated the capital, Hekmatyar's army would seize key installations and take over the city. He would use that as a launchpad of legitimacy to form a new government of his own, an Islamist government, predicated on a strict interpretation of Quranic law. Once his grip on the country was solidified, he would, as Sands and Kazizai write, quote,

encourage Muslim states throughout the world to form a pan-Islamic political, economic, and military bloc capable of challenging U.S. hegemony. The bloc would recognize Arabic as the official language of Islam, manufacture its own weapons, establish an international Islamic court, and allow Muslim citizens to travel to and from the different nations within its territory without being subject to the usual border controls. If Muslims found themselves under attack or being oppressed in another part of the world,

the Bloc would come to their aid." Like I said, Hekmajar was dreaming very, very big.

He wanted to create a sort of Islamist EU, an international coalition of Muslim countries that would fill the vacuum left by the Soviet Union and rise up to oppose the influence of the American empire. By this time, the U.S. State Department was on to Hekmatyar. They realized too late that the CIA had made a big mistake in stuffing fistfuls of cash into this guy's pockets. I mean, they probably should have been tipped off by the fact that he wouldn't even shake Ronald Reagan's hand, but...

Here we are. U.S. diplomat Peter Thompson outlined the danger Hekmatyar posed in a secret cable to Washington in September 1991.

"An extremist seizure of Kabul would plunge Afghanistan into a fresh round of warfare, which would affect areas adjoining Afghanistan. Should Hekmatyar or Sayyaf get to Kabul, extremists in the Arab world would support them in stoking Islamic radicalism in the region, including the Soviet Central Asian republics, but also in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere in the Arab world."

End quote. In Hekmajar's view, American imperialism was a disease, a plague that pulled the people of the world farther and farther from God, and Hekmajar believed that he was the one man who

who could lead this struggle. That grand, idealistic sense of purpose was wrapped up and tangled with what was probably a narcissistic personality disorder. Hekmatyar could not accept the idea of an Afghanistan in which he was not calling the shots. Anything less was an insult to his talent and a huge mistake for the country. It had to be him or no one else.

For most clear-eyed observers of geopolitics, Hekmanjar's master plan sounded like an insane pipe dream. But to him, it was very real. In many ways, it was his life's work. But there was one man who stood in the way. One person who threatened to derail all Hekmanjar had fought and bled and dreamed and worked for.

The Lion of Panjshir, Ahmed Shah Massoud. In 1992, Ahmed Shah Massoud was 39 years old, but the famously handsome guerrilla leader looked and felt much older. As an Islamist scholar who met with Massoud around this time wrote, quote,

and misery and the heavy responsibility of a jihad placed on him since he was very young. The heavy scars in his soul and body have taken away his youth." When the Soviets finally pulled out of Afghanistan, Massoud realized what a dangerous and as he put it, quote, crucial time this was. Najibullah's government was not long for this world. That was clear to anyone with a functioning brain cell. But the big question on everybody's mind was who would rule over Afghanistan and

once Najibullah was gone? And by extension, what would the new Afghanistan even look like after they were finished tearing the old one down? We've heard about what Hekmatyar wanted to do, but what did Massoud want to do? What kind of Afghanistan was he trying to build? Now, I spent a very large chunk of part three and the opening salvo of this episode drawing sharp distinctions between Massoud and

and Hekmatyar. And there are plenty to choose from. Hekmatyar is generally not a very nice man, and Massoud is generally a pretty decent one. But it would be disingenuous and simplistic to frame Massoud as the perfect white knight galloping forth to save us from the evil, mustache-twirling Hekmatyar. Now that's a much easier story to understand, but it's not a truthful one.

The reality was there was a considerable amount of overlap in Massoud and Hekmatyar's ideas about what Afghanistan should look like. As Steve Cole writes, quote,

Hekmatyar and Massoud both agreed that communist and capitalist systems were both corrupt because they were rooted in jahiliyyah, the state of primitive barbarism that prevailed before Islam lit the world with truth. And Steve Cole goes on later in his book: "Hekmatyar and Massoud also accepted that Islam was not only a personal faith but a body of laws and systems, the proper basis for politics and government. The goal of jihad was

was to establish an Islamic government in Afghanistan in order to implement these laws and ideals. End quote. Both Hekmatyar and Massoud wanted to remake Afghanistan in the image of Islam, but the difference was in how they wanted to do it, how far they wanted to go, and what would come afterwards.

Massoud was a moderate. He believed in working with people, sharing power, making life better for the people of Afghanistan. He didn't want to topple the world order or cultivate violent extremist cells around the globe. He just wanted to take his country, a place that had been torn apart by war and political upheaval for as long as anyone could remember, and make it into a place where people could actually live their lives in peace.

Last episode, I told you a story about how when Massoud was a kid, he'd punched out three bullies who were ganging up on a weaker kid at school. And that, I think, encapsulates Massoud's personality. He wasn't a saint or an angel, but he preferred to use his talents for violence to protect people. And he was willing to take up arms against bullies and aggressors wherever they popped up.

Whether they be foreigners like the Soviets, Marxists like Hafizullah Amin and Dr. Najibullah, or fanatical religious extremists like Gulbad and Hekmatyar. But the tragedy about Ahmed Shah Massoud, at least to me, lies in the fact that once you punch out a bully, you have to remember to pull the weaker kid back up onto his feet. And that second part proved elusive for the Lion of Panjshir. Waging a guerrilla war is one thing, but building a nation…

is an entirely different challenge. But I'm getting ahead of myself a little bit. When the Soviets pulled out in 1989, the feuding between Hekmatyar and Massoud intensified exponentially. This had been going on for years, but in the absence of a unifying adversary like the 40th Army, the two most powerful Mujahideen leaders really turned up the heat on each other in a bloody carousel of tit-for-tat violence. At one point, Hekmatyar organized a kind of mock trial for Massoud, at which Massoud is obviously not present, but

But the prosecution accused the Lion of Panjshir of all sorts of religious crimes, of being an infidel and a false Muslim, of screwing French aid workers and selling out to MI6. It was all bullshit, of course, but Hekmatyar seemed hell-bent on tarnishing his rival's position in the Mujahideen community. Hekmatyar followed that rhetorical exercise by engineering a, frankly brilliant, ambush and massacre of 30 of Massoud's most important commanders.

Massoud responded by hanging captured leaders from Hekmatyar's camp. These kinds of things start to happen more and more, and that carousel just keeps turning faster and faster and faster. And while all of this is going on, Pakistan's military brass and inter-service intelligence, the ISI,

is pulling their hair out, trying to get the Mujahideen leaders to play nice and work together. And you definitely get the sense that it was kind of like herding cats. The ongoing project of forming a cohesive Mujahideen government that could step in and replace Najibullah's regime once it was gone

is honestly one of the most Byzantine and complicated things I have ever read about in my life. It is a latticework of shifting allegiances, competing goals, personal grudges, and bureaucratic minutia. I mean, you could write 15 seasons of a TV political drama dedicated just to the Mujahideen squabbles from 1989 to 1991 alone. It

It's insane. And my favorite description of all of this comes from Chris Sands who said the Afghan political scene was, quote, an unfathomable tangle of short-term coalitions and routine backstabbing, end quote. So, suffice to say, it was very, very difficult to get these guys to work together. And they tried all kinds of configurations and cabinets and combinations, but the one thing that most sources seem to agree on is that the sticking point in forming any new government was always Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. He

He was absolutely intractable. Not only did he need to be the focal point of any government that emerged, but he absolutely refused to be a part of any government that Massoud was a part of. Massoud was willing to clench his teeth and work alongside Hekmajar in a hypothetical government.

But Hekmatyar was unwilling to return the favor. There's actually an anecdote from Night Letters, the book by Chris Sands and Faisal Minnala Kazizai, where an Islamic scholar is trying to convince Hekmatyar to work with Massoud. And he tries using a very pointed metaphor to coax Hekmatyar into a compromise. Quote,

End quote. But no amount of folksy analogies could throw cold water on Hekmatyar's enduring hatred of the

of the Lion of Panjshir. So, in the context of this political stalemate, escalating civil war, and white-hot personal vendetta, Najibullah's government finally collapses in April 1992, as the Mujahideen forces close in on Kabul. Hekmatyar is approaching the city from the south, and Massoud's forces are approaching it from the north.

On April 23, 1992, Hekmatyar's command center just south of Kabul was a bustling hive of activity. Pakistani helicopters whirled overhead, ferrying ISI operatives from Peshawar to advise Hekmatyar on strategy. His Mujahideen guerrillas strapped on ballistic vests, polished their machine guns, and tied green flags to tanks, jeeps, and APCs. The green, of course, meant to symbolize the imminent and triumphant return of Islamic rule to Kabul. Big things were about to happen.

Hekmatyar's final push into Kabul was about to begin. Well, that evening, an advisor came to Hekmatyar. He told him that there was someone calling on the radio, someone who wanted to talk to Hekmatyar directly. It was Ahmed Shah Massoud. Hekmatyar grabbed the receiver and began speaking with one of the people who he hated most in the world. And the main thrust of the conversation was, as Steve Cole writes, "...whether the two commanders would control Kabul peacefully as allies or fight it out."

End quote. There is, allegedly, a tape of this conversation. I have scoured the internet for it, but unfortunately I've come up empty-handed. But thankfully, many journalists and historians have heard it, and they have related almost word for word what was said between these two men on the eve of their climactic showdown in the capital. According to Mir Tamim Ansari, Massoud said to Hekmatyar, quote,

We should talk. I'm concerned about this Sunday. Sunday was the day that the Mujahideen were set to enter Kabul and the communist government would officially surrender. And this is Massoud speaking again. There might be trouble, because when one side enters, all the other armies and forces will enter too. The chaos that will result, the wreckage that will result, hits and blows among the Mujahideen. I want to lift these concerns by sitting down with you and your followers and

Let's work out something, establish an acceptable government, and then we'll proceed toward elections. It would be better to take these steps now, instead of getting to the stage where we're settling things by force. It would be better if you would promise me that on this coming Sunday, and at this point Hekmatyar interrupts him.

Quote, There won't be any trouble, so long as the situation that develops does not require our men, our followers, our mujahideen, to take action. We probably won't resort to aggression at this time. End quote. And that evasiveness from Hekmatyar really seems to chap Masud's ass, and he responds, Quote, You say no trouble will erupt, but I assure you, severe trouble will erupt if we don't take some steps. We are not afraid. End quote.

Everything depends on you and your followers." Then, Hekmatyar gets angry and he snaps at Massoud, "I have heard your words and I have told you my intentions." Massoud responds, "Are you telling me that you will certainly attack on Sunday? Should I prepare?" "Prepare for what?" Hekmatyar asks, already knowing the answer.

And at this point, Masood appears to lose his cool a little bit and his voice gets louder and angrier. Quote, Prepare, prepare to defend the people of Kabul, the women of Kabul, the men of Kabul, the young and old of Kabul. Prepare to defend this cruelly wounded nation. These people who by God every day call for refuge and plead to know what their future holds. I tell you, I take it as my duty to defend these people against every form of attack to the limits of my ability. End quote.

Hekmatyar had already made up his mind about what he was going to do. And as he told Massoud, quote, I must enter Kabul and let the green flags fly over the capital. We will march into Kabul with our naked swords. No one can stop us. Kabul is under threat. It must surrender and we will enter as victors. End quote. And the conversation ended shortly after that. At a

At around this same time, in Peshawar, Pakistan, six out of seven of the Mujahideen factions agreed to an interim government that would include Ahmed Shah Massoud as defense minister, Gulbadin Hekmatyar as prime minister, and a series of presidents that would transfer power in short succession to one another until elections could be held. Everybody accepted this arrangement, except for the lone dissenting party, Hekmatyar's faction. As his rep in Peshawar made clear, quote,

Hekmatyar can't agree to anything that includes Ahmed Shah Massoud. Civil war between Massoud and Hekmatyar seemed like a foregone conclusion. Hekmatyar was intent on entering Kabul as a conquering hero, and if any of his fellow Mujahideen tried to stop him or got in his way, well, that was their misfortune. Steve Cole describes the mood in Hekmatyar's camp on the eve of the assault. Quote,

Hekmatyar went to bed believing that he would roll into the capital and triumph in the morning. He led prayers with the Arabs who had come to Charasayab, that's the name of the little village his command center was located at. He recited verses from the Quran that had been recited by the prophet after the conquering of Mecca. "So we went to sleep that night, victorious," recalled one Arab journalist.

It was great. Hekmatyar was happy, everybody at the camp was happy, and I was dreaming that the next morning, after prayer, my camera at the ready, I will march with the victorious team into Kabul. But Afghans are weird. They turn off the wireless when they go to sleep, as if war will stop. So they switched the wireless off, we all went to sleep, and we woke up early in the morning. We prayed the dawn prayer and spirits were high.

Hekmatyar also made a very long prayer. The sun comes up again, they turn on the wireless, and the bad news starts pouring in.

convinced that Hekmatyar had no intention of compromising, Massoud had preempted him. End quote. On April 26th, the vanguard of Hekmatyar's army that had filtered into Kabul was steamrolled by the full force of Massoud's northern alliance. Massoud had assembled a fearsome coalition that spanned the ethnic and ideological spectrum. Atheist Uzbeks, Shia Pashtuns, former communists from Najibullah's regime, they all fought under Massoud.

It was a force that Hekmatyar's army, well-armed and well-funded as it was, could not withstand.

As Sands and Kazizai write, quote, And they go on to say that Massoud's forces, quote,

End quote. At the end of the day, Hekmatyar was a masterful politician and a brilliant sermonizer, but he was not much of a field commander. And in Kabul, he was up against the field commander of all field commanders. His blind hatred of Ahmed Shah Massoud had convinced him that he could defeat the man people called the Afghan Napoleon.

the lion of the Panjshir, the student of Che Guevara's theories, and the humbler of the Soviet 40th Army. In matters of war and tactics, Ahmed Shah Massoud was like a bird in the sky, and Hekmatyar was just a man without a parachute. In a handful of days, the battle for Kabul was over. Hekmatyar's men were running for their lives, trying to disguise themselves as Massoud's men just to slip out of the city with their lives intact. Hekmatyar listened to the reports that came over the radio with a mix of rage, shock,

shock, and disbelief. He would never set foot back inside Kabul, he realized. He would never fly the green flag of Islam over the capital and take his rightful place as leader of Afghanistan. His army was, as Sands and Kazizai write, quote, not simply defeated, it was utterly humiliated. And,

End quote. On April 28, 1992, Ahmed Shah Massoud entered Kabul riding on top of a tank strewn with flowers. The spitting image of the conquering hero Gulbadin Hekmatyar had envisioned himself as. The dark prince's humiliation was matched only by the jubilant mood of Massoud's arrival in the city. As Steve Cole writes, quote,

End quote. Journalist Sandy Gall describes the city's mood when Massoud's Mujahideen took control of Kabul. Quote,

Within a day or two, Kabul was in fit. In Chicken Street, the famous shopping district, the markets were crammed with food. Flower stalls were ablaze with roses. People thronged the streets and restaurants and tea houses were full. Thousands of refugees were pouring back into Afghanistan from Pakistan and Iran, where they had been surviving in camps for over a decade. It was the biggest population movement in the world at that time.

A United Nations official told me when I visited Kabul in July 1992, quote, 10,000 a day, 300,000 a month, which is the size of the entire Cambodian refugee problem. By the end of the year, 1.5 million Afghans had returned home. End quote. It was an outcome few could have predicted when Massoud set up shop in the Panjshir Valley some 14 years earlier with 30%.

30 men, a handful of rifles, and 130 bucks. Gall goes on, quote, Massoud's capture of the capital was the final victory of the Afghan resistance and of the decade-long campaign backed by the United States against its rival superpower. It was an irony that Massoud, who had long been marginalized by the ISI, the CIA, and the U.S. State Department, was the one who delivered the

End quote. But not everybody was super psyched about the Mujahideen arrival in Kabul. As one historian explains, quote,

Some of those in Kabul who had lived under communism for 14 years with everything that it had brought, Soviet-style education and culture, women in the workplace, vodka in the shops, were horrified at the arrival of the Mujahideen. Many who had been tied to the Russian and communist governments left the country. Indeed, some of the Mujahideen were rough and illiterate, and some were hardline fundamentalist Muslims who viewed the communists as treacherous and city ways as debauched.

Masood, however, was a moderating influence among them, preventing an attempt by Rabbani, that's the interim president, to ban women from reading the news on television and from the workplace in general. End quote. But Ahmed Shah Masood knew the fragile, hopeful peace would not last.

The interim Mujahideen government was built on the thinnest foundation of cooperation. Already, elbows were starting to bump as the various guerrilla groups arrived at the capital. And while Hekmatyar's fighters had been driven from the city, they were hardly a spent force. Hekmatyar was down, but most definitely not out.

As Sands and Kazizai write, "Masud knew Hekmatyar better than anyone and understood that he could never accept defeat. Embarrassed in front of the entire Muslim world, Hekmatyar would find a way to hit back." Masud was right. A handful of miles outside Kabul, Hekmatyar stewed and boiled and seethed. His great prize had been taken from him, not by the Soviets, not by the Americans, but

but by Ahmed Shah Massoud, the bookish Kabul University wallflower who had somehow convinced the world that he was a decent Muslim. A man who cut deals with the Soviets, who hid in his little valley and shunned help from their Islamist brothers in Pakistan. A coward and a traitor to Islam. Golbat and Hekmajar could not live in a world where Ahmed Shah Massoud had power in Kabul. So he decided that if he couldn't have Kabul, no one could. On

On the outskirts of the city, Hekmatyar gave the order to his artillery engineers to bring up their rocket batteries. He told them to rain destruction on the capital, day after day, night after night, month after month. As long as Massoud was in Kabul, Hekmatyar would make the city suffer.

On May 3, 1992, just five days after Ahmed Shah Massoud triumphantly entered Kabul on a tank strewn with flowers, the following passage was printed in that day's edition of the Washington Post. Quote,

Rockets and shells continue to crash into residential neighborhoods fired by the forces of fundamentalist guerrilla leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Hundreds of civilians lie in hospitals lacking electricity, water, and basic sterilization equipment. More arrive each day. Heavily armed, ethnically divided guerrillas and militiamen prowl the city streets, defending patchwork blocks from their rivals, speaking in heated tones about their various enemies, and sometimes looting homes and shops.

End quote. Throughout the course of the Soviet-Afghan War, from 1979 to 1989, Afghanistan's capital of Kabul had remained mostly untouched by the war. The vast majority of the fighting between the Soviet 40th Army and the Mujahideen took place out in the wilderness, the mountains, the valleys, the rural areas.

If you were to walk down the streets of Kabul during the Soviet occupation, you would have seen a fairly intact and prosperous city. There was food in the shops, robust electrical grids, apartment complexes, and bustling markets. It was a city under Soviet occupation, of course, but it was a city more or less at peace.

Well, in 1992, the war finally came home to Kabul. When Ahmed Shah Massoud's forces swept into the capital and sent Hekmatyar's green flag-waving mujahideen scurrying back toward the outskirts of the city, there was the briefest flicker of optimism. A thin sliver of hope that the six other mujahideen factions could get their shit together, stop bickering amongst themselves, and form a cohesive, moderate, democratic Afghan government guided by Islamic principles.

As Ahmed Shah Massoud described it, quote, "'Our main aim is to establish a framework based on principles which give every nationality, every tribe in Afghanistan its own rights, so there would be no further tribal conflicts, a framework which could be made to lead to democracy, a parliamentary system. Since we had our role in defeating the old regime, we want to play a major role in establishing such a system. We feel it as a moral and Islamic responsibility, like a burden on our shoulders.'"

The question of whether the people will elect us will not worry us. What is more important for us is to establish such a principle or such a base for the future.

End quote. The basic idea at the time was that Massoud would be defense minister. The role of prime minister was still open to Hekmatyar, if you wanted it. But Hekmatyar, always the uncompromising radical, refused to play ball. Any government that included Massoud was a non-starter. It didn't matter that Massoud was one of the best military leaders and most effective coalition builders the nation had to offer. Hekmatyar refused to take any part in a government where he would be forced to share power with his old enemy.

Instead, he opted to shell and bombard the city with indiscriminate rocket fire day after day, night after night, week after week, month after month. Kabul, which had remained largely unscathed by the Soviet presence and the Afghan communist government, was slowly, painfully, systematically demolished by some of the very people who had come to liberate it. For residents of Kabul, it was a rude awakening and a painful initiation.

into the realities of civil war. Hekmajar's rocket attacks became a fact of daily life. They screeched and roared off their platforms like oversized bottle rockets outside of the city, landing in residential areas, government buildings, marketplaces. One observer remembered that the rockets, quote, fell like rain, end quote.

Hundreds, even thousands of people were often killed in the space of a single day. One woman described what she had seen during one of these attacks to a journalist in the immediate aftermath. Quote, It was about 4 p.m. and I was baking some bread outside over a fire and suddenly there was a big explosion. I took cover on the ground. I got up and I could see this woman here and she was just running about. Her son had been sitting near this wall outside where the artillery landed.

and he was completely blown up. The woman here was running about, collecting pieces of his flesh in her apron, and crying. Her son's name was Saki. He was completely blown up, disappeared. Her grandson, Mukhtar, was also killed in the same explosion. End quote. A medical official at the local hospital told Human Rights Watch, quote, At any moment, a missile could fall. When you were outside, you never knew if a missile would fall on your head.

End quote. Kabul's hospitals were soon overflowing, as one journalist working in the city recalled, quote,

I remember pretty terrible scenes from those days from the hospital. I saw children, kids, women wounded, kids with their legs blown off. I once saw some kids arriving at the hospital in a car and their legs had been blown off by a bomb and they were just lying there in the backseat of the car. Yeah,

End quote. That summer, half a million people fled into the countryside to escape the rocket attacks in Kabul. The capital was supposed to be a beacon of new possibilities and renewed promise for a nation finally free of foreign influence. Instead, it had succumbed to a self-eating disease. As Mir Tamim Ansari put it, quote, the Soviets had destroyed the Afghan countryside. Now Afghans themselves destroyed the cities. End quote.

When journalists and diplomats demanded an explanation from Golbatin Hekmatyar on why he was indiscriminately murdering people he had professed to want to govern, he simply demurred and deflected. As Sandy Gall remembers, quote, Hekmatyar was more than economical with the truth. It hardly seemed to enter into his calculations at all. I asked him how he justified his repeated rocket attacks on Kabul and the deaths of so many civilians. He

He dismissed this as "baseless propaganda" and said "we were attacked first. He spoke softly, but he reminded me of a spider waiting at the center of a web." As Hekmatyar shelled Kabul, the six other Mujahideen factions began to carve and divvy up parts of the city like slices of a pie. Any grand ideas of cooperation and compromise withered on the vine.

Each Mujahideen party had vastly different ideas about what Afghanistan should look like. There were Sunnis, Shias, Sufis and Wahhabis, Tajiks, Uzbeks and Pashtuns. Hekmatyar's brazen disregard for law and order just gave the individual warlords the excuse they needed to create their own mini fiefdoms within Kabul. They were like warring mafia families, each defending their turf. The city soon became fractured. Chris Sands called it, quote, a

a grotesque tapestry of warring ethnic enclaves. Steve Cole called it, quote, a dense barricaded checkerboard of ethnic and ideological factions. And Sandy Gall just said the city was on, quote, the edge of anarchy. But whatever words you chose to describe it, the effect was essentially the same. Life became unlivable in Kabul. There were reports of mass rape, torture, and looting. Sunnis beheaded Shias.

Packs of rabid dogs roamed the streets. Even the city's infrastructure collapsed. As Steve Cole writes, "The electricity in Kabul failed. The few remaining diplomats husbanded petrol for generators and held conferences by candlelight. Roads closed. Food supplies shrank, and disease spread. About 10,000 Afghan civilians died violently by the year's end." The violence and chaos never seemed to stop.

It was occasionally punctuated by brief moments of brittle reconciliation among the Mujahideen factions, which quickly collapsed back into fighting, all against the backdrop of Hekmanjar's incessant and vindictive rocket attacks. Historians Sands and Kazizai sum the whole situation in Kabul up in this heartbreaking passage from their book Night Letters. Quote,

After 20 years of oppression, insurrection, invasion and occupation, Afghanistan seemed locked in a downward spiral of collective madness, with Kabul as the epicenter of this psychosis. The city's avenues had become borders between feuding communities. The river, a slurry of excrement and trash. The mountains that had once held the capital in a warm embrace now squeezed it of life. Children spoke of gin.

evil Islamic spirits haunting certain streets, while snakes and scorpions crawled through the ruined cityscape. No longer able to afford traditional building materials, people used ammunition crates to reinforce the walls of their homes." And it's hard to even describe how this "failure" of governance affected Ahmed Shah Massoud. Ten long years they had struggled against the Soviets, then another three years to bring down the Afghan Communists.

And now, when they had finally won, when they'd finally had the ability to make life better for the Afghan people and show the world that they were more than bickering tribes, they'd blown it. He'd blown it. As Chris Sands writes in Knight Letters, quote, "...the nation's capital was falling apart upon his watch. For a man proud of his own military discipline and prowess, there was no greater shame."

End quote. But for Massoud, the worst part wasn't Hekmajar's rocket attacks or the fracturing of the coalition. It was the conduct of the Mujahideen. What had begun as a noble, honest, well-meaning jihad against the Soviets had mutated into something deeply ugly and very far from the Prophet's teachings. As Sands and Kazizai write, quote,

Ever since Massoud's forces first established control over Kabul in 1992, they had torn around the city in old Russian jeeps, music blaring from boomboxes, gesturing obscenely at passers-by.

From the vantage points of their mountain outposts, gunmen shot civilians for sport in the streets below, betting cigarettes on who could score the most kills. Uzbek troops were notorious for the practice of baka-bazi, a form of pederasty in which effeminate young boys are made to dress like women and sexually abused.

The fighters of Wadat hammered nails into the skulls of their prisoners and stole ancient artifacts from Kabul's museum. None of the factions were winning. All they had succeeded in doing was tarnishing the legacy of the Mujahideen's historic victory over the Soviets. End quote. It was nauseating, but Massoud could not deny, as the most powerful military leader in the country, he had blood on his hands. As a close friend of Massoud's remembered, quote,

Those were the worst years for all of us, and I think certainly the worst years for Commander Massoud.

End quote. Ahmed Shah Massoud strikes me as a particularly tragic figure. He wanted, more than anything, to do right by his country, to kick out the communists, kick out the Soviets, marginalize extremists like Hekmatyar, and just make it work. But the reach of his ideals exceeded the grasp of his political abilities. He was a brilliant strategist, a military genius, a kind and decent man, and he still failed miserably.

Masud had prevailed against one of the most powerful empires in world history, but now he couldn't even keep the lights on in his nation's capital. But what did the rest of the world think? Was the international community really going to just sit back and watch Afghanistan burn itself to the ground?

Basically, yeah. A prominent Mujahideen commander named Abdul Haqq warned U.S. Ambassador Peter Thompson in the winter of 1992, quote, "...Afghanistan runs the risk of becoming 50 or more separate kingdoms. Foreign extremists may want to move in, buying houses and weapons. Afghanistan may become unique in becoming both a training ground and munitions dump for foreign terrorists and at the same time, the world's largest poppy field."

This, understandably, deeply alarmed Thompson and others in the State Department. After the Soviet Union had fallen, the United States had cut its funding for the Mujahideen. In their eyes, the enemy had been defeated. Jihadist pawns like Hekmatyar had played their role well enough, and Washington quickly adapted a hands-off approach. But many people in the U.S. State Department could see the writing on the wall, and they worried about the consequences of abandoning Afghanistan to its fate. As Ambassador Thompson wrote, quote,

Why was America walking away from Afghanistan so quickly, with so little consideration given to the consequences? U.S. perseverance in maintaining our already established position in Afghanistan, at little cost, could significantly contribute to the favorable moderate outcome, which would sideline the extremists,

Maintain a friendship with a strategically located friendly country. Help us to accomplish our other objectives in Afghanistan and the broader Central Asian region e.g. narcotics, stinger recovery, anti-terrorism. We are in danger of throwing away the assets we have built up in Afghanistan over the last 10 years at great expense. Our stakes there are important, if limited in today's geostrategic context.

"The danger is that we will lose interest and abandon our investment assets in Afghanistan, which straddles a region where we have precious few levers." End quote. In his book, Ghost Wars, Steve Cole describes another guy from the US State Department named Edmund McWilliams, who also expressed his concern about Afghanistan in a confidential cable in 1993. Quote, "The hands-off policy of the United States serves neither Afghan interests nor our own.

The absence of an effective Kabul government has also allowed Afghanistan to become a spawning ground for insurgency against legally constituted governments. Afghan-trained Islamic fundamentalist guerrillas directly threaten Tajikistan and are being dispatched to stir trouble in the Middle East, Southwest Asian, and African states. And this is Steve Cole commenting, The McWilliams cable landed in a void. End quote.

By this point, the Clinton administration was in power and it was distancing itself from the Cold War struggles of yesteryear. In their eyes, they were just bigger fish to fry at home and in other parts of the world. Afghanistan was someone else's problem. As a member of President Clinton's team put it, "...nobody wanted to return to the hotspots of the Reagan-Bush years. They just wanted them to go away. Afghanistan was just one of those black holes out there." End quote.

Meanwhile, for everyday people in Afghanistan, it seemed like there was no one to turn to for help. The Mujahideen were tearing the country apart, unable to put their personal drama and ideological dogma aside to actually build a new nation out of the rubble the Soviets had left behind. The international community was powerless to help at best and smugly indifferent at worst. The people of Afghanistan were desperately looking for a savior, a miracle, an end to the violence and chaos and lawlessness.

Well, in 1994, a new faction emerged that intended to give the people of Afghanistan exactly that. To give them the law and order they so desperately craved. Ladies and gentlemen, let's meet the Taliban.

Back in part two of this series, we met a woman named Jan Goodwin. If you'll recall, Jan was an executive editor at Ladies Home Journal in New York, and in 1985, she snuck into Afghanistan to travel for three months with a small band of Mujahideen to cover their guerrilla war against the Soviets.

But Jan had not just decided to take that very risky assignment out of the blue. There was an experience she had a year before that convinced her she needed to see the war zone for herself. Do you remember what it was? Bonus points if you do, but if you don't, that's okay. She visited an Afghan refugee camp inside Pakistan.

And she was horrified by what she saw there. Around 84-85, the Soviet 40th Army was at the height of what was called their depopulation campaign, literally emptying the Afghan countryside of its people so they could not provide aid and shelter to the Mojahedin. The Soviets carpet-bombed villages, destroyed farms...

pulverized infrastructure, you name it. Well, all those people had to go somewhere, and many of them surged over the borders in every conceivable direction. But the largest proportion of refugees, around 4 million people all told,

fled to the southeast and settled in Pakistan. As Jan walked through the camps, she would have noticed all kinds of upsetting details. The poverty, the disease, the missing limbs and the choking stench. But the most unsettling thing she would have noticed was that the vast majority of these refugees were kids. One Pakistani camp official claimed that, quote, "...three-quarters of the population was under 15 years of age."

The refugee camps were full of more than a million adolescents and teenagers who had lost everything. Their homes, their friends, their siblings, their parents. The very building blocks of a normal, healthy childhood were suddenly and irreversibly gone. Imagine, just for a second, that you are an orphan in a Pakistani refugee camp in 1985. You're, say, 11 or 12 years old.

Your parents are gone, either dead, missing or off fighting somewhere with the Mujahideen. You have four or five siblings to look after, no source of food or income, except sporadic handouts of oil, flour, tea and salt from the United Nations. If you're lucky, you have a drafty tent that you can cram everybody into at night, and everyone around you, millions of people for a dozen miles in any direction,

are in the exact same situation. Your suffering is not unique or special. You just have to survive any way you can. You're angry and scared and alone, and here's the kicker, bored out of your mind. There's pretty much nothing to do in these camps, except scrape by day to day and reflect on the terrible hand life has dealt you. But there was one constructive way for these Afghan orphans to channel all that sorrow, restlessness, and rage. Asmir Tamim Ansari writes, quote,

Hundreds of thousands of teenage boys were cooped up in these camps with no outlet for their restless teenage energy and nothing but horror to build memories around.

The boys did, however, have one escape hatch from their boredom. They could go to a madrasa. End quote. A madrasa is a fundamentalist Islamic religious school, and there were well over 2,000 of them clustered along the Pakistani-Afghan border in the mid-1980s. About a quarter of a million young Afghan boys ended up cycling through these schools.

The madrasas provided room and board completely free of charge, they offered safety, mentorship, basic education, and most important of all, structure, an antidote for the hopeless chaos of the camps. For a penniless and parentless teenage refugee, that sounded like a pretty sweet deal. But the madrasas had another motive. The teachers in these schools looked at these scared and homeless Afghan orphans and saw balls of fresh clay to mold into whatever they saw fit.

Asmir Tamim Ansari writes, quote, What the religious teachers gave their captive audiences was a narrative. They told the wide-eyed refugee boys about a perfection that had existed just once in history, during the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad, at

at Medina. For one generation, they explained, a whole community had lived in absolute obedience to the laws of God Almighty, and that obedience had made them mighty, because God accompanied the original Muslims into every battle, and against God, no force could stand. This was not wild-eyed raving, it's pretty much the standard core of the Muslim narrative, the context.

was what made it volatile. In recent years, the Muslim world had been awash with expectations of an apocalyptic battle coming up between God's people and the devil's. And this narrative came to permeate the camps in Madrasas. Religious teachers preached that the rebirth of the perfect community would mark the beginning of the battle. Yes, if only some group of Muslims could live as the people of Prophet-guided Medina had lived, by those exact rules, by that code,

the world would be saved. Boys who were suffering through the worst childhood on Earth were allowed to imagine that it might be their destiny to establish the community that would save the world.

As a journalist named Ahmed Rashid wrote, "These boys were what the war had thrown up, like the sea's surrender on the beach of history. They had no memories of the past, no plans for the future, while the present was everything. They were literally the orphans of the war, the rootless and the restless, the jobless and the economically deprived, with little self-knowledge."

End quote. To these boys, the idea of reclaiming a war-torn Afghanistan and shaping it into the perfect Islamic community gave them purpose and direction. It let them feel in control of their own lives at a time when they couldn't even control where their next meal would come from.

As the scholar Thomas Barfield writes, quote,

and the future is so uncertain. End quote. These students and the madrasas, spoon-fed a one-dimensional and regressive interpretation of Islam, cut off from any other intellectual influences and riled up to believe it was their God-given mission to implement a mystical utopia, grew up to become the movement we now call the Taliban. Now, initially, Taliban was not the name of an organization or a political movement. Talib is just the Pashto word for student. Talib.

Taliban is the plural form of that word. So all Taliban means is students. Sometimes it's translated as seekers of knowledge. Well, long story short, against the backdrop of the Soviet-Afghan war, the madrasas on the Pakistani frontier became a hatchery for a splinter religious ideology that was poised to dominate the country.

By now, it's 1994. Two years have passed since Ahmed Shah Massoud captured Kabul and dashed Golbat and Hekmatyar's dreams of ruling Afghanistan. But Massoud and the new government he was a part of had failed to create order out of chaos.

24 months of vicious civil war among the seven Mujahideen factions had reduced the capital to a glorified pile of rocks. No electricity, no running water, no economy, nothing. Just bullets, bombs, and unmitigated misery, as Thomas Barfield writes, quote, Historically, Afghanistan got rid of foreign occupiers by making the country so ungovernable that they wanted to leave. This strategy, perfected during the decade-long struggle to expel the Soviets, now

now came to haunt the Afghans themselves. Having achieved the sobriquet "graveyard of empires" for their 19th and 20th century successes against the superpowers of the age,

the Afghans now began digging a grave for themselves. No faction was able to establish either political legitimacy or military hegemony, but none was willing to compromise with its rivals either. It was as if the country had developed an autoimmune disorder. Powerful antibodies fatal to foreigners were now directed at the Afghan body politic itself.

End quote. At this point, the everyday people of Afghanistan felt profoundly betrayed by the Mujahideen. During the war against the Soviets, they had idolized the guerrillas as heroes and holy warriors. But now, the holy warriors didn't seem so holy. They weren't making life better for the people of Afghanistan. In fact, they were making it actively worse. The country had degraded into one giant battlefield, dominated by a feuding patchwork of robbers, smugglers, warlords, and heroin cartels.

Even well-intentioned leaders like Ahmed Shah Massoud seemed powerless to break the cycle of violence. And then, like a bolt of lightning, the Taliban appeared. The foundational and possibly mythical origin story of the Taliban begins in 1994 with a humble, one-eyed mullah, or religious teacher, named Muhammad Omar. And I'll let Mir Tamim Ansari tell the story as only he can. Quote,

Legend has it that sometime in the spring of 1994, the Prophet Muhammad appeared to Mullah Omar in a dream, offered him his cloak, and asked him to save the Muslim people. A few days later, the story goes, Omar heard about a particularly horrible crime in his neighborhood. Some brutal Mujahideen gangster had kidnapped two girls for himself and his men to rape. Mullah Omar told his followers to do something about it.

And they did. Not only did they rescue the girls, they hanged the rapist from a gun barrel of his own tank as a warning to evil doers. There was a new sheriff in town. I say "legend has it" because this story might be apocryphal, I know of no evidence that it was told at the time. This and many similar stories were told later and often when the Taliban were developing an image of themselves as incorruptible knights of Islamic piety and disseminating this image to the public. An image that, it must be said,

they undoubtedly believed to be true. The Taliban started out as a tiny band of vigilantes, lynching Mujahideen warlords who preyed on young girls. But within a matter of months, they had snowballed into a national movement that could stand toe-to-toe with the most well-armed Mujahideen factions. The orphans of the Soviet-Afghan war were all grown up, and they flocked to Mullah Omar's new army of God by

by the tens of thousands, unified by a grand purpose. With Qurans in one hand and Kalashnikovs in the other, they wiped out local bandit gangs, made the roads safe for trade and travelers, and imposed the kind of stability that the people of Afghanistan had been so desperately craving. But the Taliban were much more intense from an ideological standpoint than the Mujahideen. According to Stephen Tanner, quote,

The Taliban espoused the same doctrine as the Mujahideen, only more so. On every point, they were more literal, more simplistic, more extreme. In their own view, what they were was more pure. They had no interest in discussing what was best for Afghanistan because they already knew what was best: the Sharia. They were here to enforce the law, as they understood it, without compromise or deviation. This is what the bulk of the cadre undoubtedly believed.

And Tanner goes on later in his book, quote, "...they admired war because it was the only occupation they could possibly adapt to. Their simple belief in a messianic, Puritan Islam which had been drummed into them by simple village mullahs was the only prop they could hold on to and which gave their lives some meaning." End quote. But the Taliban movement would likely have never been more than a footnote in history had it not been for the assistance of one very powerful benefactor, Pakistan.

By 1994, Pakistan's ISI was looking at the situation in Afghanistan the way you might look at a burning building across the street. This had gotten way out of control, way out of hand. The Soviets were gone, sure, but the victorious Mujahideen had somehow managed to break what was already broken, plunging the country into more violence, more chaos, and more despair.

At the center of the problem, in Pakistan's view, was their once-promising protege, Gulbadin Hekmatyar. For going on 15 years, the ISI had gone out of its way to funnel disproportionate amounts of weapons and money to Hekmatyar. They'd given him every tool and resource he could possibly need to take over Afghanistan. Sophisticated weaponry, monetary support, and invaluable political patronage. Not to mention a safe harbor in Peshawar to rest his weary little head.

And what had he achieved? Nothing, except the undying hatred of every man, woman, and child in Kabul, the enmity of the other six Mujahideen parties, and the agitation of the international community. Like a gambler at the end of a bad night, Pakistan realized Hekmatyar was a losing horse, a money pit that needed to be put out to pasture. So rather than continue putting their chips on a volatile personality like Hekmatyar, the ISI opted to engineer a fundamentalist insurgency

from scratch. One that they could control. One that did not have international aspirations or decades of baggage. A fresh slate. And the one-eyed Mullah Omar and his puritanical vigilantes fit that bill perfectly. For their part, Omar and the boys were all too happy to accept death-dealing toys from Pakistan to achieve their Islamic utopia. Asmir Tamim Ansari writes, quote, Within two months, the Taliban had airplanes, automobiles, artillery, tanks, helicopters,

helicopters, sophisticated radio communications, guns, bullets, and

and money. Pakistan professed amazement at how quickly these plucky youngsters were progressing, and on their own too, for Pakistan denied having anything to do with creating or arming the Taliban. According to Pakistani spokesmen, the Taliban captured all their materiel from the Mujahideen or acquired it from commanders who joined them. At the same time, Pakistani officials flung open the gates of those Afghan refugee camps and let thousands of recruits pour across the border to join the new force.