Kill Yamamoto: The Mission to Avenge Pearl Harbor - Part 2

Conflicted: A History Podcast

Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

Shopify is the global commerce platform that helps you sell at every stage of your business. Whether you're selling your fans' next favorite shirt or an exclusive piece of podcast merch, Shopify helps you sell everywhere.

Shopify powers 10% of all e-commerce in the U.S. Allbirds, Rothy's, Brooklinen, and millions of other entrepreneurs of every size across 175 countries. Plus, Shopify's award-winning help is there to support your success every step of the way.

Because businesses that grow, grow with Shopify. Sign up for a $1 per month trial period at shopify.com slash income, all lowercase. Go to shopify.com slash income now to grow your business, no matter what stage you're in.

Hello and welcome to Conflicted, a history podcast where we talk about the struggles that shaped us, the tough questions that they pose, and why we should care about any of it. Conflicted is a member of the Evergreen Podcast Network, and as always, I'm your host, Zach Cornwell. You are listening to the conclusion of a two-part series on Operation Vengeance, the U.S. military's plan to ambush and assassinate

Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese admiral who planned the infamous surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. In part one, we spent a lot of time getting to know Yamamoto, who he was as a person. We learned about his talents, his character flaws, what he cared about, and who he cared about. We followed his career through the Japanese Navy as well as his close, even close,

even intimate, relationship with the United States and its people. We also talked about the stark contrast between Yamamoto "the man" and Yamamoto "the propaganda" caricature. After Pearl Harbor, Americans were as fixated on Yamamoto as they would be on Osama bin Laden in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks. But unlike Osama bin Laden, Yamamoto was not an ideologue or a fanatic.

He had warned Japan over and over again not to go to war with America. It was suicide, he said. But despite Yamamoto's best efforts, Japan's war in China and an alliance with the Nazis made a clash with the United States a foregone conclusion. And Yamamoto was forced to put together the only war plan that offered even the slimmest chance of success.

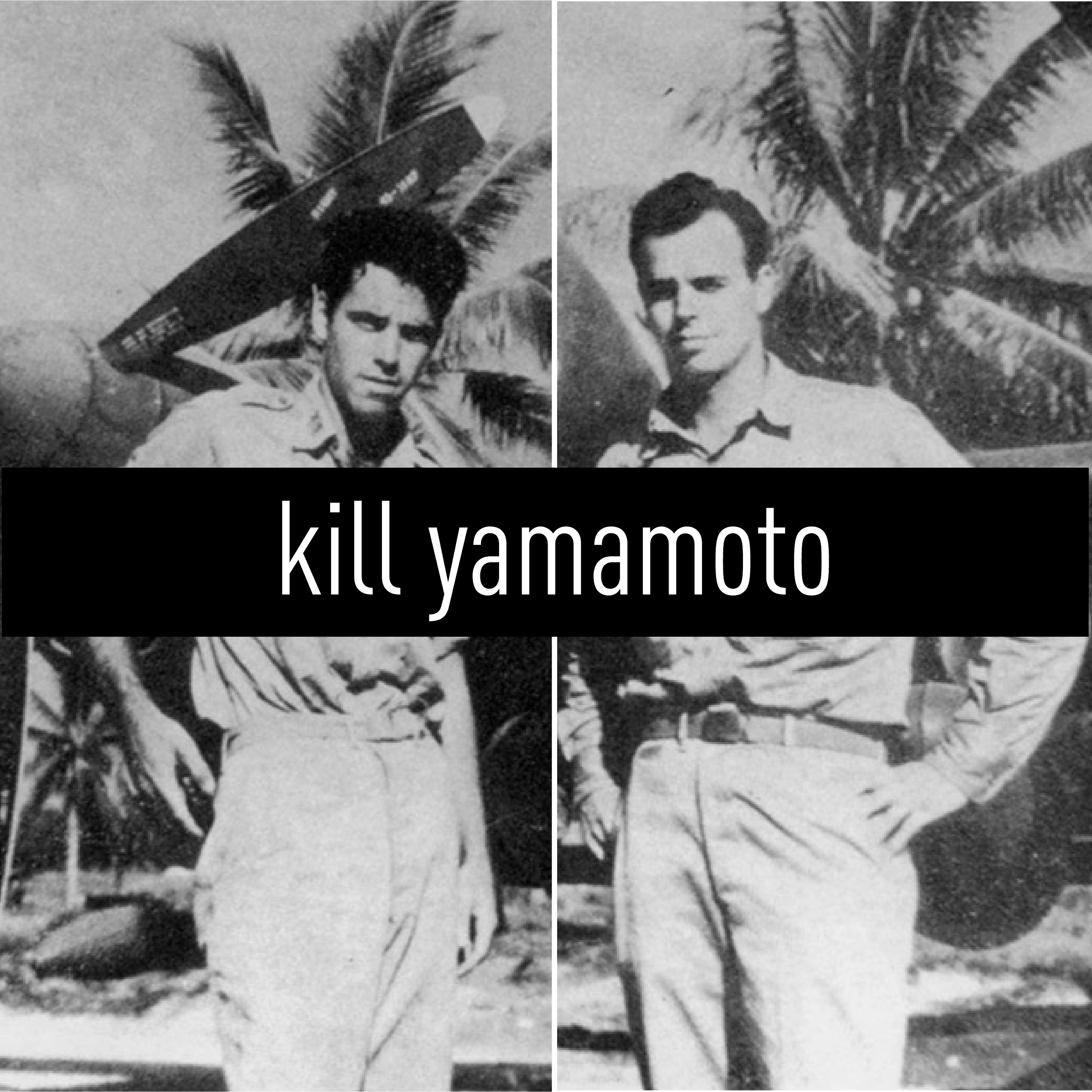

We also met two young American pilots, Tom Lanphier and Rex Barber, who in the months following the Pearl Harbor attack found themselves shipped out to Fiji to complete their flight training. Almost immediately, the two became close friends. But Rex Barber was already beginning to see the shades of ambition in his friend Tom,

that would end up fracturing their relationship just a few years later. All of these different threads were about to intersect in a fateful battle over the jungles of the South Pacific in a hastily but meticulously planned mission to kill America's public enemy, number one. So now that we've had a quick refresher on part one, let's dive in and conclude our story. Welcome to episode 22, Kill Yamamoto, the Mission to Avenge Pearl Harbor, part two.

June 7th, 1942 was probably one of the worst days of Isoroku Yamamoto's life. It was the day that he learned the full scope of what had happened at the Battle of Midway. It had been six months since the stunning attack on Pearl Harbor, and in that time, the Japanese had been running wild all over the Pacific. Victory followed victory followed victory. It felt like they could not lose, like they were invincible.

At home in Japan, the flags fluttered and the propaganda swooned over the indomitable Admiral Yamamoto, the man who had brought the United States Navy to its knees in the blue bays of Oahu. But Yamamoto knew better. Even as stacks and stacks of fan mail arrived at his flagship, he could not take much comfort in what he called, quote, the small success at Pearl Harbor. As he bitterly confided to a friend, quote, the...

Mindless rejoicing at home really is deplorable. We are far from being able to relax at this stage. The sinking of four or five warships is no cause for wild celebration. It is not so hard to open a war as it is to conclude it.

End quote. Because there was a piece of unfinished business from the Pearl Harbor attack, and it stuck in Yamamoto's brain like a splinter, a nagging, irritating X-factor that he could not let go of. Even though dozens and dozens of ships had been sunk and destroyed at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had not managed to destroy America's aircraft carriers. Now, if you'll recall, Yamamoto was obsessed with aircraft carriers. He saw them as

as the ships of the future and a must-have for the navies of the present. A perfect weapons system blending the mobility of a seafaring vessel with the range and firepower of aircraft. And he knew that unless he destroyed America's carrier fleet, Japan would never be truly safe. His fears were confirmed in mid-April of 1942.

The very same people who'd been waving flags and singing the praises of Yamamoto in Tokyo were shocked to hear the roar of American planes over their capital. Bombs fell, homes were burned, people were killed, even the emperor's palace had almost been hit.

The Doolittle Raid, as it came to be known, only did miniscule damage, but the psychological shock and whiplash it incurred on the Japanese people was incalculable. Japan's leaders had always promised their people that Americans would never ever be able to attack the home islands. Like, ever. And yet, they had done it. Well, it soon came to light that the raid had been launched from, what else, an American aircraft carrier in the Northern Pacific.

And, just like that, everybody was on Yamamoto's wavelength. "You see," he said, "aircraft carriers are the most dangerous weapon in a modern navy's arsenal. The United States will never be completely out of the fight unless we get the carriers. We have to get the carriers."

Well, that sounds easy enough, but the problem was finding them. And during this period in the mid-20th century, radar and reconnaissance technology were still extremely primitive. There are no satellites, there's no drones or Google Earth imaging. Yamamoto needed to find these US carriers, but it was like trying to find a needle in a needle stack. Like the two missing phantom fingers on his left hand, they were there, but not there. So, he decides to set a trap.

at a lonely little sand spit called Midway Island which lies roughly midway between Japan and the continental US. The idea essentially was to attack the US installation at Midway, draw the American carrier fleet into a decisive engagement, and destroy it. As historian Dan Hampton helpfully summarizes, quote, "By invading Midway Island, the Admiral sought to lure the remaining US aircraft carriers into a strategically tactical counter-strike."

End quote.

Now, before we get into this, I just want to set some expectations. Midway is one of those battles that is a bit of an obsession for World War II buffs all over the world.

The armchair generals have been dissecting this thing for the better part of a century, so I'm not super interested in examining it from a tactical, play-by-play perspective. There are tons of great documentaries and podcasts that go really deep into the details of Midway. But for our purposes, the Battle of Midway is important because of what it did emotionally to the people in our story. Particularly, what it did to Yamamoto. Leading up to the battle, Yamamoto was very, very nervous.

It was probably the most anxious that he'd felt since his first naval engagement against the Russians back in 1905. The same battle where he'd lost the two fingers on his left hand.

And while he wasn't in any "mortal" danger this time, he was putting everything on the line. In his eyes, Japan's very future would be decided at this little sandbar in the middle of watery blue nowhere. Yamamoto's anxiety was also compounded by other factors, unrelated to the coming showdown with the Americans. As we've mentioned before, Yamamoto had a wife and four children at home in Japan, but his thoughts were rarely with them.

Instead, he was thinking about his lover in Tokyo, the gorgeous geisha Chiyoko Kowai. Yamamoto and Chiyoko wrote to each other constantly. Sometimes they talked on the phone, and to be apart for so long, with their future together clouded by the uncertainty of war, well that was agonizing for both of them. They were 19 years apart in age, but their bond went far beyond the typical geisha-patron relationship.

There was real love and affection here. But in March of 1942, Yamamoto received some alarming news. Chiyoko had fallen very ill. She had come down with pleurisy, which is a severe inflammation of the lungs. Yamamoto could hear it in her ragged little breaths over the phone. I mean, she could barely talk. In her own words, she, quote, "...hardly spoke by telephone due to so much coughing. I lost patience with tears."

End quote. But even severe illness could not come between the two star-crossed lovers. On May 13th, Chiyoko hopped on a train from Tokyo bound for the coastal city of Kure for a secret rendezvous. When she got off the train, she saw Yamamoto, disguised in civilian clothes, spectacles, and a gauze mask. He traveled all the way from the front just to see her. As Chiyoko wrote later, when she stepped onto the platform, quote,

"My darling awaited me, and I was wild with joy." Yamamoto scooped her up and literally carried her to the car. Yamamoto and Shioko spent the next four days and four nights holed up in a hotel room. At this time, they'd known each other for about ten years, and their affair was almost as old. Each of them had taken other lovers in that time, as a geisha, Shioko had plenty of clients, but she was an expert, according to another geisha at quote,

keeping her heart and her body separate. End quote. The true north of her internal compass always pointed towards Yamamoto, and his to her.

In the old days, they would have spent those four days and nights in a tangle of sheets and sweat and passion, but this time they just talked and spent time in each other's arms. Chiyoko was extremely ill. A doctor even had to come and give her injections periodically as part of her recovery regimen. But she was tough. Yamamoto had seen men go through hell in war, but even a battle-hardened commander like him was impressed by her resiliency. As he told her, quote,

Your spiritual strength in overcoming illness day by day is amazing indeed." After their four days were up, Yamamoto took Chiyoko back to the train station, and they said a short, tortured goodbye. As the geisha wrote later, "Though I was so weak that I could not hold your hand strongly, you were very, very strong in holding my hands. I wished I could get off the train and remain beside you. When the train started to move,

I hated to loosen our firmly held hands." Yamamoto and Shioko's last glimpse of each other was on that train platform in the city of Kure. They didn't know it at the time, but they would never see each other again.

Chiyoko was on Yamamoto's mind as he prepared to set the trap at Midway on June 3, 1942. Not only was he heart-sick, but an intestinal infection had turned his stomach into a pressure cooker of cramps and pangs of discomfort, and he was soaked in sweat as he looked at his watch, waiting for news from the fleet at Midway. And then, the reports start coming in.

In the space of six minutes, Yamamoto watched his entire war plan dissolving like cotton candy. The aircraft carrier Kaga? On fire. The carrier Soryu? On fire. The carrier Akagi? On fire. And the carrier Hiryu? Disabled and out of action.

Somehow, the Americans had known that they were coming, and they had set a trap of their own. Towards the end of part one, we talked about the American codebreakers at Station Hypo, the workaholic analysts who were systematically unraveling Japan's secret naval code in a basement office known affectionately as "The Dungeon." Well, by the summer of 1942, they had it fully deciphered. They could read Yamamoto's communications like a children's book. And through some very clever counterintelligence,

They knew exactly where the Japanese were going in advance. The accuracy of the codebreakers in Hawaii was almost supernatural. As Donald A. Davis writes, quote, "...when contact actually was made and the battle commenced, that analysis was off by five degrees, five miles, and five minutes."

End quote. The codebreakers at Station Hypo had pinpointed almost the exact latitude and longitude of the Japanese carriers, and the American fleet had hunted them down with ruthless efficiency. In the end, Yamamoto lost four of his precious aircraft carriers, a battlecruiser, and hundreds of planes.

The famous gambler had rolled the dice and come up with snake eyes. As I said at the top, June 7th of 1942 was probably one of the worst days of Yamamoto's life. A Japanese Navy clerk described the mood on the bridge of Yamamoto's flagship, quote, The admiral and his staff looked at one another, their mouths tight shut. There was an indescribable emptiness, cheerlessness, and chagrin. End quote.

It is difficult to even comprehend how Yamamoto would have felt at this point. He had been a gambler all his life. He'd watched roulette wheels land on black when he'd picked red. He'd watched stacks of money disappear. He'd seen lucky streaks evaporate and fortunes won and lost.

But this was like a gut punch. He must have felt like the wind had been knocked out of him, and the gravity of the loss at Midway would have sent visceral panic racing across his synapses. From Yamamoto's perspective, he had held Japan's fate in his hands, and he totally blew it.

Of course, on a tactical level, it wasn't really Yamamoto's fault. There were myriad mistakes and miscalculations that could be blamed on his subordinate commanders, but Yamamoto was never, ever the kind of guy to blame the people under him. He did not throw people under the bus. The buck stopped with him, and he knew it. As he said in the aftermath of the battle, quote, I am the only one who must apologize to the emperor. End quote.

Back in the States, the media framed the Battle of Midway as long overdue payback for Pearl Harbor. But in Japan, the people were told absolutely nothing about the catastrophic loss. Yamamoto had always pushed for transparency with the Japanese people. He believed that they needed to be just as clear-eyed about what they were facing as

as he was. Well, the government censors didn't have much faith in the average Japanese citizen. In their eyes, it was best that they believed that Japan was winning naval battles hand over fist, guided by their very own god of war, Isoroku Yamamoto.

But in reality, Midway kinda broke Yamamoto. He became reclusive, quiet, even joyless. The same man who could charm a roomful of American cowboys or do a handstand on the deck of a ship could barely get out of bed. And it's easy to see why. When the news of their losses at Midway crackled over the radio on June 7, 1942, Yamamoto knew in his gut that the war was lost.

His government would labor under the delusion of a possible victory for the next three years, but he understood that it was just a matter of time. America's war machine, the thing that he had long feared, had been activated. As Winston Churchill had once said, "It was a boiler that, once heated, could not be put out." But Yamamoto was a slave to appearances. He was expected to play it all out, the best he could. He'd already lost the high-stakes game of chess

but he had to see it out to the conclusion, and hopefully save as many Japanese lives as he could. Just as he dutifully married a woman he did not love, and fathered kids he did not want, Yamamoto would do what was expected of him, even to the bitter end. And while many Americans saw Midway as successful revenge for Pearl Harbor, others found it unsatisfying. They wanted a body. They wanted Yamamoto dead on a slab.

And circumstances were moving into place that would soon bring the Admiral into American crosshairs.

Tom Lanphier could smell the island of Guadalcanal before his plane's wheels even touched the ground in December of 1942. Six months had passed since the Battle of Midway. The war in the Pacific had been raging, and yet Tom, along with his good friend Rex Barber and the other pilots of the 70th Squadron, had been stranded on the Fiji Islands in an endless purgatory of training exercises and empty routine.

Tom was getting anxious and frustrated. It had been an entire year since Pearl Harbor and yet still, he had not flown a single mission against a Japanese target or a Japanese pilot. Now, it certainly wasn't for a lack of skill. Tom was one of the best pilots in the 70th. His buddy Rex was just as good, if not better. And they were chomping at the bit to get a taste of the action. Admittedly, life had been pretty good on Fiji.

The pilots spent their time on the ground playing cards, sipping grain alcohol and chasing nurses. But that got really old really fast, especially when all they had to do was switch on a radio to hear that an entire war was raging on. Without them.

Tom Lanphier didn't want a glorified vacation on Fiji in relative comfort and safety. He wanted to carve out a name for himself in this war. He wanted to be a legendary pilot, a hero, just like his dad, Tom Lanphier Sr., had been in World War I. Tom had even confided to his friend Rex that he had aspirations to the U.S. presidency, as he tried to explain to his pal, quote, Rex, you're over here because you're patriotic. Well, I'm here because I'm patriotic.

But I have another reason." But for a career in politics to flourish, Tom needed a sparkling war record. Hell, any war record. And right now, all he had to his name was a few hundred hours of flight time and a pretty good tan. Well, after months upon months of doing nothing, Tom and the other pilots got some very good news. They were being called up. They were going to be sent into the action, to some patch of godforsaken jungle east of Papua New Guinea.

None of them had ever heard the name Guadalcanal before, but in the months to come, they would experience things there that would burn those four syllables into their brains forever. Guadalcanal. It's a name we all know pretty well in modern history circles. It was part of the Solomon Islands chain. As celebrated author Jack London had once written, quote, If I were a king, the worst punishment I could inflict on my enemies would be to banish them to the Solomons.

End quote. If Fiji was a paradise, Guadalcanal was hell on earth. The island was quote, slug-shaped, as one historian puts it. But there were more than just slugs crawling through the dense jungle mountains. On an evening stroll through Guadalcanal, you might encounter crocodiles, venomous snakes, centipedes, three-inch wasps, poisonous spiders, swarms of mosquitoes, or a giant colony of white ants all in the same 20-foot radius. It rained constantly.

constantly almost every single day everything was wet or damp or soaked all the time which results in smells that the human nose does not often encounter I mean it's a jungle so everything is constantly decaying and rotting and fertilizing and growing on top of itself and then there's the heat triple digits choking humidity

This was a far cry from the cool coconut groves of Fiji. I mean, to put it simply, this is not a place where people are supposed to live. These kinds of conditions destroy the human body. I mean, think of it kind of like a slow cooker or braising meat. Constant heat and moisture and pressure over a very long period of time, and you just start to slowly fall apart. As Donald A. Davis writes, quote, The human organism...

simply broke down under the extreme tropical conditions. Even the strongest men suffered substantial weight loss and aching joints, and their thinking could become so clouded that they might even lose the will to live." One pilot from the 70th summed it up pretty well, saying, quote, God, it's spooky. End quote. Since the summer of 1942, fierce fighting had been raging on the Canal, as some Americans called it, or by the island's codename, Cactus. But

But most guys just called it the shithole. The Japanese hated Guadalcanal too. Many of their soldiers called it Starvation Island. Now, without getting too deep into the strategic weeds, Guadalcanal became a key piece of real estate in the war plans of both Japan and the United States. And in the back half of 1942, it was the axle around which the entire Pacific War revolved. Tom, Rex, and the rest of the pilots of the 70th Squadron had wanted a challenge, and

And they were about to get it. As Tom climbed out of the cockpit of his fighter and his boots hit the crunchy, crushed coral of Guadalcanal's airstrip, he knew that this would not be anything like Fiji. And he was happy. He couldn't wait to blast his first zero out of the sky. Rex and Tom's immediate commander, the man who they would be answering to day to day, was a guy named Major John Mitchell. But everyone just called him

Mitch. Now, in the pantheon of boring white guy names, John Mitchell is pretty up there. But for the purposes of this episode, it is very important to commit the name John Mitchell to memory. Now, I always try and resist the urge to flood these episodes with names that don't really mean anything to the story that we're telling. It ends up being just a distraction from the people that we're actually here to learn about.

And thankfully, this cast is pretty small in comparison to some other episodes. We've got Yamamoto, his geisha lover Chiyoko, and the two flyboy buddies Tom and Rex. Well now, it is time to round out the cast with our last figure. Major John Mitch Mitchell was a small, sprightly little good old boy from Mississippi. He was only 27 years old, that cursed age of all prodigies.

But Mitch was a natural-born leader of men. In the corporate world, you'll often hear people talk about the coaches versus players theory. And the general idea is that people tend to fall into two categories, right? You're either good at execution, scoring points, or a player, or you're good at leadership, coaching, a player, or a coach. Well, John Mitch Mitchell was a player and a coach.

By the time Tom Lanphier and Rex Barber hopped out of their cockpits onto Guadalcanal, Mitch had been fighting and flying on the island for three months. He was a certified ace. He had eight or more confirmed kills in the air. He was an absolute pro. He was the LeBron James of that squadron and everybody knew it. Like Isoroku Yamamoto, Mitch was a good boss, although his leadership style was entirely different. Yamamoto could be warm, but also very strict and unbending.

While Mitch relied on a softer touch, draconian discipline would not work in a punishing environment like Guadalcanal. He needed to be a respite from their suffering, not an extra layer of it. As Mitch said in his own words, quote, "...I tried to lead my guys on a loose rope. I knew you had to lead by example more than anything else. And I watched what I did, and I tried my best in every way. So I couldn't just hand out orders. They were learning art as well as skill."

I tried to make them aggressive too. Good fighter pilots can't think defensively. I wanted to make them killers so that they could survive. I didn't mind if they got into fist fights or chased women. I just kept telling them that they were the best. I approved of a certain amount of wildness in them.

End quote. When the first batch of pilots had arrived on Guadalcanal in the fall of 1942, some of the pilots were scared to death of encountering a Japanese Zero, the hummingbirds with machine guns, remember? Veteran pilots from the Navy had told some terrifying stories about the Japanese airmen. Well, Mitch tried to squash that fear right out of the gate in his unmistakable southern drawl. Quote, Alright, any of you guys who believe that crap from the new squadron, let me know it. I mean it.

The road fork's right here. Don't you believe one goddamn word they say. It's pure, unadulterated horse shit. They haven't really fought zeros, but you sure as God will. If any of you think that we can't lick chaps, say it now, and you can stay right here. Nobody's going with me who can't cut the mustard. Y'all are getting hotter and hotter. He meant better at flying. You can handle anything that flies if you stick to our teamwork. You're great pilots, and don't you forget it.

End quote. That, ladies and gentlemen, is the kind of boss you want to have in a war zone. Now, it's tempting to read that speech and picture some grizzled, gray-haired general, but again, Mitch was only 27 years old at the time. He was younger than me. And that's the amazing thing about some of these pilots. You look at pictures of these guys, and they look so, so young, like high school kids. Well, luckily, an airplane doesn't really care what age you are, just that your reflexes are fast enough.

Needless to say, the men of the 70th Squadron thrived under Mississippi Mitch's energetic leadership. For the ambitious Tom Lanphier Jr., it was like a release valve had been hit. Tom was a really smart guy. He was a Shakespeare buff. He had quite the pedigree. But he also had a compulsive need to prove himself, not only to his famous father back home, but to himself. And a few weeks after he arrived at Guadalcanal, he bagged his first zero.

It was Christmas Eve 1942. Tom had gone up in his fighter plane to guard an attack run of American bombers when a Japanese Zero shrieked into his field of vision. As Tom would tell it later in a very self-congratulatory tone, quote, "...I found myself close enough behind the Zero, who was ignorant of my lethal presence, to have him filling my whole gun sight."

End quote. Tom squeezed the trigger and the Zero exploded as it was ripped apart by .50 caliber rounds. As Tom remembered, it, quote, instantaneously converted into a firecracker. End quote. It was the best Christmas present Tom could have ever hoped for. He'd only been on Guadalcanal three days.

To the amusement of the other pilots, Tom also claimed that he'd brought down a second Zero, which no one could confirm. He said he'd done it, but no one had seen it, so he got credit for just the one. Tom's buddy Rex Barber got his first kill around the same time too. The two friends had been itching to get into the fight, and to experience such instant validation was an amazing feeling. It was a joy even their commander Mitch had to acknowledge. Quote,

I won't say you remember it like it's your first girlfriend, but it's something like that, the first time you shoot down an airplane." The pilots spent Christmas Eve of 1942 drinking, celebrating, decorating little shrubs as impromptu Christmas trees, and singing joke carols like "I'm Dreaming of a White Mistress." They drank grain alcohol out of Clorox bottles and listened silently to the chaplain give mass. As a soldier named Bob Miller remembered, quote,

the moon shining through the palms on a clear blue background the roar of the flying fortresses pulling their loads of death and destruction into the air the candle-lit expressions on the faces of men the chant of the mass all very story-bookish

In the weeks and months that followed, Mitch's pilots, Tom and Rex among them, just started racking up kills. I mean, you read about this period in the Guadalcanal campaign, and it seems like the Americans are just shooting fish in a barrel. Two days after his first kill, Tom got two more zeroes.

Rex Barber scored a miraculous kill on a Japanese bomber shortly after, earning him the Silver Star. A few months later, they both won Silver Stars for destroying seven Japanese float planes and strafing a nearby destroyer. There's a really funny anecdote about an American admiral who was touring the island at this time and he was pleasantly surprised at all the success in the air. And he said to his guide, quote, "'This place is a goddamn tiger pit.'"

It's like this every day? End quote. And the guide answered, quote, It's a little light for a Thursday, but it'll pick up. End quote. Tom and Rex were both clearly extremely talented pilots in a squadron full of extremely talented pilots. But with accolades and success came comparison and envy. As a lieutenant named Jay Buck remembered, quote, Selfish motives did begin to appear. Petty jealousies. End quote.

Tom Lanphier's demeanor, once loquacious and fun, began to rub people the wrong way. He seemed more arrogant, more aloof. His colorful stories started to grate. His bookishness, love of Shakespeare and the ability to quote philosophers at will, once considered lovable eccentricities, now just reminded the other guys of the very different walk of life Tom had come from. Tom was the son of a famous colonel.

aviation royalty with political connections, a big shot who talked about chatting with Charles Lindbergh and seeing Scarlett O'Hara naked. In the war, they were all equals. But when it ended, if it ever ended, Tom would toss them all aside like yesterday's beer cans. As one commander noted with a touch of resentment, quote, he was a handsome guy, Mr. Personality, end quote.

Tom also started exhibiting a troubling pattern of exaggeration. No one could spin a tall tale like Tom Lanphier. He had a storyteller's eye and a former newspaperman's instinct for embellishment.

But, some of his claims outright stretched credulity. For example, back when they had been stationed at Fiji, Tom had asked to be taken along on a bomber run as a liaison from their squadron. When he returned, he told a story that the bomber had been attacked by Japanese Zeros and that he'd personally taken command of one of the bomber's .50 caliber guns in

and fired back. But none of the airmen on the bomber would confirm the story. The inconsistencies were weird, but people just chalked it up to Tom being Tom. Then there was the tale of the Jap in the jungle. Apparently, you can actually find this story in Tom's autobiography. Now, to be fair, there are no copies of that autobiography in print, at least that I could find, so I'm working off a historian's secondary account, just to be transparent. Anyway...

According to his autobiography, Tom was tagging along with a marine patrol through the jungle on Guadalcanal. Someone apparently had wanted an airman's opinion on this or that part of the terrain. Well, somehow, Tom became separated from the group and found himself alone in a deep, dark jungle. Through the din of chattering birds and buzzing insects, Tom heard a rustle in the bushes.

Suddenly, a lone Japanese soldier burst out of the foliage and sliced Tom's left hand with his bayonet. According to Tom, this is what happened next. "I squeezed his slender neck as we both fell to our knees, and he died struggling." But yet again, no one saw it happen, no one could confirm it, and there is no record of Tom Lanphier ever receiving medical treatment for a wounded hand.

Then there was the claim of getting the second zero on his fourth day on Guadalcanal. He definitely got the one, but he'd adamantly insisted he'd gotten two. But, as Donald A. Davis writes, quote, "...the accounting rules for aerial combat victories were simple. A pilot got credit for downing an enemy plane only if there was a witness to the crash."

because a wounded pilot might be able to nurse his plane back to safety. A probable meant no one could say for certain exactly what had happened to an enemy plane that had been damaged in a fight,

although it most likely crashed. Things happen so fast in a dogfight that the eye plays tricks. Reports are easily confused and, as Admiral Yamamoto himself once noted, fighter pilots tend to exaggerate. Therefore, no proof, no victory was a hard and fast rule of the pilot fraternity and it would play a huge role in the events to come. End quote. Now I just want to take a second to stop and lower the temperature a little bit.

It's not that Tom Lanphier was necessarily lying about this stuff. That is not the implication that I'm trying to make. We don't know the full truth of these stories, we'll probably never know. What we do know is that Tom was a brave, brilliant pilot, a credit to the US Army.

But he was also a human being, with flaws, like any of us. And the truth was he had a tendency to embellish. When faced with uncertainty or ambiguity, Tom Lanphier always, always erred on the side of his own reputation. He was, as one historian wrote, a quote, super salesman. And the product that he was selling was the legend of Tom Lanphier. Maybe it was stress, maybe it was the heat, but Tom's bonds with the other men, even his good friend Rex,

began to fray. They were still incredibly close and trusted each other implicitly, I mean they had to, to not do so was an occupational hazard, but the low-key days and the white beaches of Fiji were long gone. The rot of Guadalcanal, what one historian called quote, "an evil nature," was beginning to take hold. But on the other side of the Pacific, near the sapphire shores of Hawaii, magic was happening.

On April 13th, 1943, a message was intercepted by the American analysts at Station Hypo, the code-breaking cabal in Pearl Harbor responsible for the intelligence that had led to the victory at the Battle of Midway. In the aftermath of the gut-punch loss at Midway, the Japanese deduced that the reason their fleet had been intercepted and crushed was that the Americans had broken the code.

There was no other reasonable explanation, so they immediately scrambled the code and went with the new cipher. For the Americans, the Champagne High of Midway was quickly followed by the hangover realization that their code-breaking efforts were back to square one. They were more or less starting from scratch.

And this time, the Japanese had learned their lesson. In the months to come, they periodically changed the code to stay one step ahead of Station Hypo. In less than a year, the Japanese had changed it three or four times. It was a constantly moving target. But Station Hypo's massive IBM tabulating machines could still work out about 15% of the messages. And that remaining 85% was where the codebreakers of Station Hypo thrived.

15% wasn't ideal, obviously, but it was a running start. It was enough to contextualize the intercepted messages, and under the hum and glow of fluorescent lights in a windowless basement, the analysts worked on cracking the code.

Each message was a partially solved puzzle, a high-stakes game of Mad Libs that could cost actual lives if you got it wrong. Hundreds of intercepted messages flooded into Station Hypo every single day. But on Tuesday, April 13th, one message in particular practically jumped out of the stack. It mentioned the Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet. And there was only one Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese fleet.

Isoroku Yamamoto. After a long night filled with cups of black coffee and frenzied Japanese to English translation, the codebreakers realized that it was a travel itinerary. And it was shockingly precise. It's said that in exactly five days' time, Admiral Yamamoto would be visiting troops on the front lines near Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

And to get to those forward bases, he would be flying in a modified passenger bomber escorted by six Japanese Zeros. The codebreakers even knew the exact times of takeoff and touchdown. This was huge. Easily the biggest piece of information they'd come across since Midway. As Lieutenant Colonel Red Laswell, the man who deciphered the message, told one of his linguists, quote, "...we've hit the jackpot."

A few hours later, a memo was soaring up the chain of command to the commander-in-chief of the American fleet, Admiral Chester Nimitz. When Nimitz opened up the file folder and read the report the station hypo guys had put together, his face barely twitched. But there was obviously a current of excitement under the Admiral's famously stony exterior. "'Our old friend Yamamoto,' he said. He looked up at the codebreakers in his office and asked, quote, "'Well, what do you say?'

Do we try and get him?

For Nimitz, it wasn't as simple as signing a kill order. Taking out Yamamoto could have serious implications for the American war plan in the Pacific. For one thing, it would signal to the Japanese that yet again their code had been broken, which would result in an immediate scramble and the Americans would be starting from scratch all over again. Being in the dark like that could cost lives, or worse, ships. They had to ask themselves one very hard question.

was one man, even the man who had planned Pearl Harbor, the man Americans loathed second only to Adolf Hitler himself, really worth the risk.

The debate was certainly had at the highest levels of the US military and government. The intelligence guys argued that killing Yamamoto would be an invaluable blow to Japanese morale. One officer named Edwin P. Layton, a man who had known Yamamoto from his days as a naval attache in DC, argued that Yamamoto was quote "unique" among their people. He's the one Jap who thinks in bold, strategic terms. He is head and shoulders above them all.

He represents the very heart of the Japanese Navy." But others made the point that Yamamoto's special and unique disposition cut the other way too. The Japanese would eventually lose this war. That was never in any real doubt, it was only a matter of time. But there would be no negotiating with the Bushido fanatics in the Japanese army.

But maybe Yamamoto might be more reasonable. Maybe he could convince the Emperor that it was a lost cause. Maybe keeping Yamamoto alive would bring a swifter peace and save more lives in the long run. But they all knew the clock was ticking. Yamamoto was going to be stepping on that plane in less than four days, no matter what. After some brief deliberation, Nimitz decided it was worth the risk.

The morale boost at home would be huge, and killing the architect of Pearl Harbor would be a body blow to the Japanese Navy. So, he closed the folder and said, quote, Let's try it. The order flowed like mercury back down through the chain of command, and on Friday, April 16th, just 48 hours before Yamamoto was due to depart,

a message arrived on the desk of the commander of the Combined Air Forces on Guadalcanal. It commanded him to pick out some of his very best pilots for a top-secret mission to intercept and kill Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Three names came to mind immediately. The very best pilots on Guadalcanal. Tom Lanphier, Rex Barber, and their CO John Mitchell.

The message ended with a postscript, quote, it appears the peacock will be on time. Fan his tail. Whoa, landing an account this big will totally change my landscaping business. It's going to mean hiring more guys and more equipment and new trucks for the new guys to drive the new equipment in. I don't know if I'm ready.

You can do this. And Ford Pro Fin Simple can help. Our experts are ready to make growing pains less painful for your business with flexible financing solutions that meet the needs of your business today when you need them. Get started at FordPro.com slash financing.

On the afternoon of Saturday, April 17th, 1943, Tom Lanphier was packing his bags. He, Rex, and the other pilots were scheduled to go on leave the next day, a long overdue and well-deserved vacation from jungle rot, flak, and .50 caliber bullets on Guadalcanal. Well, amid the hustle and bustle of the airfield, Tom spotted a Jeep coming down the road, and in the passenger seat was his CEO, Major John Mitchell, or Mitch, as we've come to know him.

Mitch waved Tom over and told him to hop in the Jeep. He was on his way to a mission briefing, and he'd been told to bring Tom along as well. If Tom had any disappointment about the sudden revocation of his scheduled leave, he didn't show it. He hopped in the Jeep next to Mitch, and the two drove over to the big Navy headquarters tent. Tom and Mitch walked into the tent to find it filled with senior officers, like 30 people, all important Navy guys. As Tom remembered, quote,

We found every brass hat on the island. It almost felt like they'd walked into a room they weren't supposed to be in. Cigarette smoke filled the tent, such a common feature of the space that it was known jokingly as the opium den. And then all of these men turned to Mitch and Tom, and the two 20-something pilots suddenly realized that they were the center of attention. Then the Navy officers told them why they were there.

Tomorrow morning, on April 18th, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto would be on a plane just a few hundred miles away. Mitch and his boys were going to intercept him and kill him. What the brass didn't tell them was how they'd gotten the information. The secret of the broken Japanese code was so vital, so sensitive, that even the pilots going on the mission were told an outright lie. They were told that Australian coast watchers had come by the information somehow.

And initially, for whatever reason, the name Yamamoto didn't ring a bell for Mitch. But Tom quickly whispered in his ear, Pearl Harbor. Then the weight of what they were being asked to do fully sunk in, and Mitch listened quietly as the details of the proposed mission were explained. The Navy guys seemed to have it all figured out.

During his itinerary, Yamamoto was scheduled to board a ship after his plane touched down. Mitch, Tom, Rex, and the rest of a hand-picked killer squadron would sink the ship. Yamamoto would drown or burn to death, and that would be that. Mitch listened to the plan with growing irritation.

The briefing was chock full of esoteric nautical terms that he did not understand. No army pilot knew this stuff. It was like they were planning this thing in a completely different language. And the breaking point for Mitch came when the briefer mentioned that they should expect strong winds off their quote, port quarter. Mitch interrupted the briefing and blurted out in his trademark southern drawl quote, what the hell does that mean? And

End quote. All eyes turned to the 27-year-old Major. Even Tom took a second to steal an "oh shit" glance at his CO. Omich explained that the idea of getting Yamamoto while he was on board a ship was a terrible idea. Quote, "I don't know one boat from another, and even if we sink the boat, he could just jump in the water in a life vest and survive. What if there are several boats? Which one would he be on? Look, we're fighter pilots. We should take him in the air.

Tom agreed, saying, "Uh, yeah, all boats look alike to us." Mitch went back and forth with the planners for a couple minutes. He felt like they were setting him up for failure. They felt like he was being nitpicky and uncooperative. Well, finally, the highest-ranking man in the room, an admiral, shut down the argument. "Well, since Mitchell has to make the interception, I think it should be done his way." So, he asks Mitch,

Where do you want to do it? Without missing a beat, Mitch nodded. In the air, sir.

You got it, said the Admiral. And that was that. Mitch had gotten his way. Now all he had to do was make a flight plan, calculate the route, pick the pilots, brief the squadron, and have it all ready in less than 24 hours. Tom Lanphier was practically hopping with excitement as they drove back to the pilot barracks. But Mitch must have had a sobering suspicion that maybe he'd bitten off a little more than he could chew. At 435 miles round trip, he knew that this would be, quote,

the longest planned intercept ever." Nothing like it had ever been attempted, and there were so many unknowns, so many variables that they could not possibly know. As Dick Lair writes, "They had Yamamoto's basic itinerary but not his route or altitude,

Nor did they know whether he'd be on time. Furthermore, there was no way for them to know his speed or whether they'd get there at the right time. End quote. Just as the codebreakers at Station Hypo had been forced to fill in the blanks of so many messages and coded intercepts, Mitch would have to make a lot of assumptions of his own. And even the slightest error could mean failure. But he'd been chosen to make it happen, not to fret over what might go wrong. So Mitch grabbed a flashlight, a ruler, and a map,

and spent the next several hours doing math. Lots and lots of math. To ground all of his calculations, he had to assume that Yamamoto would reach his destination on time. That nothing could go wrong on the Japanese side of things. Not a forgotten pair of gloves, or an overlong conversation, or so much as a flat tire on the way to the airport.

Based on the timing of the intercepted itinerary, from wheels up to touchdown, the Admiral's passenger plane would have to fly at an airspeed of 180 miles per hour. So, Mitch based his calculations on that. They needed to catch him about 30 miles away from his destination, a massive, regional Japanese airbase brimming with anti-aircraft cannons and Zeros that could tear them to shreds if they were alerted to an attack on Yamamoto's plane.

When you read about all the details that Mitch had to work out, it almost starts to remind you of a dark, macabre version of an old-school math problem. If a plane carrying America's public enemy number one leaves an airfield 435 miles away, flying due southwest at 180 miles an hour, at what speed would an American killer squadron need to fly to catch and kill him? Well, as Mitch scribbled and scratched out calculations by lantern light, some of the Navy guys came over to help.

and they were very, very impressed with his work. As one remembered, quote, Mitchell laid out the course, speeds, gas mixture settings, and finger-to-the-wind estimates of what the weather elements would be the next day. All the credit for the planning should stop with Mitchell. End quote.

In his tent just a few hundred yards away, Tom Lanphier could barely sit still. He knew that Mitch was working up a plan of attack and he didn't know his role in it yet, but this was big. He was going to be in the killer group, he just knew it. Why else would the Brask ask for him by name? This was the opportunity, the career-making opportunity that he'd been waiting for since the news of the Pearl Harbor attack came over the radio in his San Francisco hotel room.

At midnight, Mitch called his squadron over to a big chalkboard behind the pilots' tents. Everybody was there. 40 pilots, mechanics, ground crews, everybody who would be involved in the operation the next day. On the blackboard, Mitch had written 16 names, and the pilots anxiously scanned it like students looking at the cast list of a high school musical. At the top of the list, Tom saw his name.

And he saw his friend Rex Barber's name. The two of them would be the lead fighters in the killer flight, four hunter planes who would actually do the shooting and actually bring down Yamamoto's bomber.

Mitch and the other 11 pilots would provide cover from above. As mosquitoes swarmed around the lanterns and monkeys shrieked in the distant jungle, Mitch took his guys through the plan, point by point. First of all, he explained their route, a zigzaggy nightmare over enemy territory and wide open ocean. He told them that Yamamoto would likely be accompanied by at least six and up to 50 Japanese Zeros. They would be heading into a very nasty fight.

And finally, he closed the briefing with a sobering note. The Navy brass had made it very clear that Mitch and his pilots were expected to get Yamamoto at any cost, even if that meant ramming his plane and sacrificing themselves along with it. With that, Mitch dismissed the men and told them to get a good night's rest. Takeoff would be just after 7 o'clock AM the next morning. Tom exchanged an excited glance with his wingman Rex Barber and retired to his tent to get a little sleep.

Well, the gravity of what they were about to do started to dawn on Tom. Tomorrow, they would kill the man who planned Pearl Harbor, the smug bastard who said that he intended on marching into the White House and dictating peace terms. Tom could not have asked for a more perfect assignment. He would have Mitch watching his back, his trusted wingman Rex at his side, and a very valuable trophy in his crosshairs. Tomorrow morning could be, potentially,

the most important day of his life. Maybe the future presidency of Tom Lanphier Jr. would be born right here, on a lonely airfield on Guadalcanal. The adrenaline must have been pumping, but Tom had to fall asleep somehow. A few tents over, another pilot named Doug Canning was playing an easy listening tune called Blue Serenade on his phonograph. The fighter pilots on Guadalcanal drifted off the night before the most important day of their lives to the lyrics, quote,

When I hear a serenade in blue, I'm somewhere in another world, alone with you. End quote. A love song was darkly fitting for the occasion, because the next day, they all had a date with Admiral Yamamoto.

Two weeks earlier, on Friday, April 2nd, 1943, Isoroku Yamamoto sat down in his personal quarters aboard his flagship and wrote a letter to a certain geisha back in Tokyo. It had been months since he'd seen Chiyoko. The last time he'd held her in his arms, she'd been a sickly, shivering wreck.

her lungs barely able to support an extended conversation. But somehow, she'd made a full recovery. He'd recently gotten two letters from her and he wanted to promptly respond so she wouldn't worry about him. He wrote that he was relocating much closer to the front. Quote,

"Tomorrow I'm going to the front for a short while. I will go in high spirits, since I have heard from you." He also told her that because of his grueling travel schedule he would not be able to write her for a couple weeks. But to soften that disappointment he included a lock of his hair in the envelope, as well as a haiku poem, "If I think of you as ordinary passion dictates, could I have had a dream of you, only every night."

Of course, an English translation doesn't really do justice to what was likely very beautiful phrasing in the original Japanese, but the gist was, I love you so much that even dreaming about you every single night is not enough. At least that's my interpretation, but haiku enthusiasts of the world, please feel free to enlighten me on social media. Anyway, two weeks later, on April 18th, 1943, Isoroku Yamamoto got up around dawn and got dressed.

He put on a pair of white gloves, with the two fingers on the left one tied up where his missing digits would have been. It was an old wound, a reminder of a career that had spanned four decades. The aches in his joints and the cramps in his stomach were also stark reminders that he was an old man now. He'd turned 59 just a few days after he'd sent Shioko his most recent letter with a lock of hair. He was not the spry, energetic gambler that had charmed people from New Mexico to Monaco. Honestly, he was just tired.

and he couldn't help wondering what would happen to him after Japan eventually lost this cursed, pointless war. Nothing good, probably. The Americans would insist on labeling him a war criminal for his attack on Pearl Harbor. His royal flush in Hawaii had disintegrated into a disastrous hand at Midway, and now Japan was just bleeding chips.

At one point, Yamamoto took a drag on a cigarette and turned to a subordinate and said, quote, I imagine I'll be packed off either to the guillotine or to St. Helena, end quote. It was a dark, pithy reference to the sad fate of Napoleon in the aftermath of Waterloo. But just as he'd put on a brave face for his loveless marriage, Yamamoto had a job to do. He was scheduled to visit the troops at the front, and they could not see the weak, disillusioned man that was lurking beneath the surface of the water.

of the legendary exterior. They could only see the war god. He didn't have much hope left, but he could not condemn them to desperation and despair. They were all expected to fight to the death, and he had to bolster that resolve. But Yamamoto's underlings were a little nervous about this trip. The itinerary had been transmitted by radio, and there was a danger that it had been intercepted.

As a rear admiral named Joshima complained, quote, What a damn fool thing to do to send such a long and detailed message about the activities of the commander-in-chief so near the front. This kind of thing must stop. Yamamoto wasn't that worried, though. They would be flying through their own territory, protected by six Zeros flown by some of the best pilots in the Navy. Plus, there would be not one, but two passenger bombers in the flight group.

Anyone hunting for Yamamoto would have no idea which bomber he was in. Just after 8 a.m. Guadalcanal time, Yamamoto's plane roared off the runway at the Japanese airbase at Rabaul. It was going to be a long day, full of speeches, photo ops, and strategic discussions. A long day, but hopefully uneventful. Little did Yamamoto know, his assassins were already in the air and skimming over the waves toward him at 200 miles an hour.

So, we have talked about the men who were chosen to kill Yamamoto. But before we get into what actually happened in the skies of the South Pacific that fateful morning, we need to talk about the machine that was chosen to kill Yamamoto.

On April 18th, 1943, Mitch, Tom, Rex, and the rest of the pilots were flying a fighter plane called the P-38 Lightning. Now, I've mentioned before that I'm not a huge hardware guy, I don't get super excited about the specific kinds of bullets, bombs, or weaponry that were used in these conflicts. Unless, of course, they have an important role in the story, an important effect on the human beings that we're talking about. And this is one of those cases. If the

If the Mitsubishi Zero was a hummingbird, the P-38 Lightning was a pterodactyl, a twin-engine killer Cadillac with wings that could zip through the skies at a top speed of 395 mph. This was American aerial engineering at its finest.

It was easily the fastest fighter aircraft in the Pacific theater. Enemy pilots often called it, quote, "the fork-tailed devil." And pilots like Mitch, Tom, and Rex loved this airplane. It could dive, it could zip, it could climb, quote, "like a homesick angel." And best of all, it was very easy to kill enemy pilots with this aircraft. Because the guns, the .50 caliber machine guns, were located in the nose of the plane, rather than the wings.

But when they're in the wings, you have to account more for distance and the specific angle of attack? Well, the P-38 was essentially point and shoot. These forward guns create something that's called a "cone of fire" that could turn a Japanese Zero into a "firecracker," as Tom Lanphier once put it, in a matter of seconds. But on April 18th, 1943, the P-38 Lightning's most attractive quality was its range.

Mitch and his pilots would have to fly a very long way to intercept Yamamoto, over 400 miles, and not as the crow flies. They would be changing direction multiple times over open, endless ocean with no identifiable landmarks. A normal fighter would not be able to make that flight purely because there just wasn't enough gas in the tank.

Thankfully, in addition to the internal fuel tanks, the P-38 had an external fuel tank that could be jettisoned after it was used up. Basically, the P-38 Lightning could fly farther than Zero's, faster than Zero's, and deliver more firepower than Zero's. It was the perfect weapon to put Yamamoto in the ground.

As Yamamoto's plane was taking off, Tom Lanphier had already been in the cockpit of his P-38 for 55 minutes. They'd taken off from Henderson Field about 10 minutes after 7 a.m. that morning, and almost immediately, things had started to go wrong. One plane blew a tire on the runway, another had a fuel problem in the air, and right out of the gate, they were down two valuable pilots. But they had to press forward.

Strict radio silence had to be maintained to avoid alerting Japanese radar stations in the region, and Mitch could only communicate with his 16-man squadron through little wiggles of the plane's tail or a slight dip with his wings. Mitch had planned this mission literally down to the minute. All the other pilots had to do was follow him, turn when he turned, climb when he climbed, and in truth, all the pressure was on Mitch. The entire mission was riding on his judgment.

his compass, his watch, and the hasty calculations he'd made just a few hours earlier. But, if those calculations were right, if Yamamoto was on time, and if the intelligence was accurate, and those were all big ifs, they would intercept Yamamoto at about 9.35 in the morning, about 30 miles outside of the largest Japanese airbase in the region.

When that happened, Mitch's hand-picked hunters, Tom Lanphier and Rex Barber, would do their deadly work, while everyone else engaged Yamamoto's escort of Zeros. But Mitch and his guys were fighting more than just the Japanese out there over the Pacific. They were fighting a different, more subtle kind of enemy. Prolonged disorientation, mind-numbing discomfort, and good old-fashioned boredom.

From runway to rendezvous, this would be about a two-hour flight. Now, think about what you do on a two-hour flight, from say like Dallas to Denver. Maybe you read a book, you take a nap, get a little tipsy on a few Bloody Marys, and even in the most comfortable circumstances, that two hours tends to crawl. I don't know about y'all, but I'm usually ready to leap out of my seat after a two-hour commercial flight.

Well, the route Mitch's squadron was taking had no landmarks, no mountains, no islands, no trees, nothing Mitch could rely on to let him know that he was going the right way. It was just empty, endless ocean. As Mitch remembered, quote, "...not a rock in sight, nothing except waves, and one wave looks like another."

And to make it even more disorienting, they were flying just 50 feet above the water, a necessary measure to stay below the Japanese radar scanners. Now, flying that low, that fast, and with so little visual variety, it starts to do things to the human eye and the brain.

When you're that low, an optical illusion starts to happen. You begin to feel as if you're in a bowl, and the horizon is the lip of that bowl, looming above you. And the reason this is so dangerous is because if you blink or get disoriented or dip too low, you'll smash into the waves. And if the impact doesn't kill you, no one can radio for help.

Radio silence, remember? You're done. But that's not all. The P-38, as magnificent a machine as it was, had a slight design flaw that only made itself known in these very specific mission circumstances. As Dick Lair writes in Dead Reckoning, quote: "The plexiglass bubble over the cockpit was locked tight. Ordinarily, that was a non-issue. The P-38 was a high-altitude, twin-engine fighter usually flown at 20,000 feet and above.

But now, hugging the ocean, the bubble was like a magnifying glass for the sun's unfiltered rays, and there was no way to open it. The temperature inside soared. Mitch read the gauge, 95 degrees in the cockpit. Everyone was soon soaked in sweat.

End quote. So all of these different factors start to compound. The heat, the boredom, the waves. And even though all these guys were heading towards one of the most important encounters of their lives, some of them start feeling like they're about to doze off. There weren't any white caps in the ocean to visually mark the passage of distance, and it was almost hypnotizing. Mitch and Tom and Rex and the other guys felt like they were flying in the bottom of a bowl made out of mirrors.

And again, they had to do this for two hours. One of the guys, Doug Canning, the same man who had soothed everyone to sleep the night before with his record player, started counting sharks to pass the time. And he saw all kinds of wildlife. He saw a pod of whales, Man O' War jellyfish, one colossal manta ray. Doug apparently ended up counting something like 48 sharks.

And there were moments of danger during this two-hour flight as well. At one point, a pilot clipped the waves with one of his propellers, and Mitch was terrified he'd lose a pilot. But the guy adjusted, and everything was fine. Well, at about 9.30 a.m., land, sweet, green, blessed land, came into view. After 400 miles of endless blue, Mitch heaved a sigh of relief. They had made it to their destination, the intercept point.

The island mountains held a touch of foreboding, though. As Dan Hampton writes in his book on Operation Vengeance, the craggy jungle peaks looked like, quote, a rotten tooth embedded in green gums, end quote. But as Mitch began to scan the skies, there was nothing. No planes, no zeros, no Yamamoto.

And Mitch started to think, oh my god, what if I made a mistake? What if my math was wrong? Maybe we're too early, maybe we're too late. At those speeds, even a slight deviation could have potentially sent them hundreds of miles off course. Or maybe they'd been picked up by a Japanese radar and Yamamoto had already turned back.

But then a voice came over the radio. It was old Doug Canning, the record player enthusiast and counter of sharks. "Bogeys ten o'clock high," he said. Canning's sharp eyes had found a handful of barely perceptible pinpricks leaping out of the endless blue sky like eyeball floaties. Two bombers and six fighters. Mitch's calculations had been correct. They'd found him. A lot can happen in two minutes.

On the morning of April 18th, 1943, it only took two minutes for Mitch and his squadron to kill Isoroku Yamamoto. But it was one of the most blinding, chaotic, and confusing time crunches that most of them would ever live through. When you are flying an airplane at 200 miles an hour, it is very difficult to have a clear understanding of the bigger picture. That is to say, how you fit into the larger choreography of a dogfight.

For one, the noise is deafening, there are huge tracer rounds that could cut you in half zipping through the air. The horizon is less of a constant line and more of a seesaw that dips and bobs and sways in the most disorienting way. It is very easy to see things from the cockpit of a fighter that did not happen the way that you remember them happening. Time seems to contract and compress and bend in ways that only life or death circumstances can really provoke in the human mind.

When you read accounts of what happened in the space of that handful of minutes, it is shocking how inconsistent and frankly confusing the stories are. The facts, as individual pilots tell them, especially Tom Lanphier, often do not add up. In fact, sometimes they're downright contradictory. And I gotta tell you, I've been reading about this handful of minutes for like two months straight now, and I still struggle to keep it totally coherent in my head. And the truth is, the men who lived through it didn't.

did too. Suffice to say, Tom Lanphier, Rex Barber, Mitch Mitchell, the other dozen or so American pilots and the Japanese Zero pilots all emerged from the engagement that was about to happen with very different perceptions of what had occurred. So what I'm going to try and do is tell you what did happen. Then we will look at what the men involved thought happened, and how those differing versions of reality infected their relationships with one another afterwards.

And again, this is just one of the weaknesses of the podcast medium. I can't really show you what happened with diagrams and charts, but my narration will just have to do.

When Tom Lanphier caught sight of the two Japanese planes, he counted eight little specks. As he got closer, he realized there were two bombers and six Zero fighters. Yamamoto would be in one of those bombers, although which one was anyone's guess. Rex Barber, who was flying just behind Tom to the left, noticed that the Japanese planes looked, quote, bright and new-looking, end quote.

As writer Burke Davis phrases it, quote, they sparkled in the light, streaking against the background of the mountains, end quote. For the last two hours, there had been complete radio silence. But once the Japanese were sighted, the American pilots were free to communicate. Tom's adrenaline was hammering as he heard his name squawk over the radio. It was his commander, Mitch. And Mitch said, quote, Tom is your meat, end quote.

As leader of the killer group, Tom had just gotten the green light to turn those shiny new bombers into scrap metal. Mitch and the rest of the squadron would watch their backs from 15,000 feet. Having been let off his leash by Mitch, Tom pulls back the stick of his P-38 Lightning and rockets upwards towards the two bombers. His wingman, Rex Barber, is following him on his left. And at this point, it is only Tom and Rex pursuing the two bombers. And they are closing fast. Remember, these P-38 Lightnings are like Cadillacs with teeth.

The distance between them is rapidly shrinking. But then Tom sees a problem. The Japanese escort of six Zeros is heading directly towards them. And Tom realizes that they will not reach the bombers before the Zeros reach them. So he turns hard and up at a 45 degree angle directly towards the Zeros. And Mitch is watching all of this like a choreographer of a ballet, and he starts freaking out.

Tom was not supposed to break formation and go after the Zeros. The Zeros did not matter. They were there for Yamamoto, and Yamamoto was in one of the bombers. So Mitch yells over the radio, quote, End quote.

No answer. Tom was already twisting his twin-engine P-38 upwards into a hail of gunfire. That left only one pilot pursuing the bombers: Rex Barber. Now, when I first introduced Rex in part one, I told a story about how he jumped off the roof of his family barn at the age of 11, trying to use his mother's bedsheets as a parachute.

And honestly, I really wish we'd been able to spend a little more time with Rex as a person, but your time is precious and unfortunately that necessitates some hard decisions when I'm writing these scripts. So, while with Tom off engaging the Zeros, Rex was alone pursuing the bombers. And he is approaching the two bombers so fast that he almost collides with the closest of them. But even if he had to ram them, he had to take them down. As Rex said, quote,

My primary job, as I saw it, was to get that bomber. End quote. The lead bomber finally comes into Rex's crosshairs, and he pulls the trigger. As Dan Hampton writes, quote, As he raked the fuselage from tail to nose, some 23 pounds of lead smashed into the thin-skinned bomber for each burst. Metal was cut apart, seat cushions disintegrated, and people were shredded.

End quote. The bomber's left engine erupts into flame and smoke and it starts plummeting toward the jungle canopy. But before Rex can watch it crash and confirm his kill, he is fired upon by a Japanese Zero. So he twists away and evades the fighter. As he does this, he catches sight of the second bomber, which he then pursues along with another pilot, a man named Besby Holmes.

and then together they pepper that second bomber with bullets until it crash lands in the water. While all of this was happening, Tom Lanphier had evaded the other Japanese Zeros and had turned back in the direction of the bomber Rex had just fired upon. In his autobiography, Tom describes rocketing towards the bomber at a perfect right angle and firing upon it. He said he saw the right engine burst into flame and then the wing ripped off and the bomber plunged into the jungle and crashed.

The entire engagement, from the sighting of the Japanese planes to the crash landing of the second bomber, had only taken a handful of minutes. One of the pilots said that it only took 60 seconds, which is not likely, but it felt fast is the point. Circling at 15,000 feet, Mitch decides he's gotta call this thing. It seemed like the two bombers were down, and if Yamamoto was in either of them, he was most likely dead.

Their fuel tanks were running dangerously low. It was time to go home. So he radios Tom, Rex, and the rest of the squadron, quote, let's get the hell out of here.

End quote. Back on Guadalcanal, the American Navy and Army personnel were anxiously awaiting some sign, any sign, of how the mission had gone. They knew the gravity and the significance of this operation. I mean, killing Yamamoto had been on almost every American serviceman's mind since Hawaii's pristine waters had been clouded with blood and oil less than two years earlier. The powdered eggs and spam that made up their breakfast that morning went down a little harder, not knowing if their friends were safe.

It's also worth noting that many airmen experience the death of their friends a little bit differently than sailors or the infantry. They just never came back. There's a beautiful sentence in Donald A. Davis' book, Lightning Strike, that captures that feeling of losing friends on missions like this. Quote, End quote.

Well, just after 10 a.m. on April 18th, a voice came over the radio. It was Tom Lanphier, the leader of the killer group in Mitch's squadron. Quote, I got that son of a bitch. He won't be dictating any peace terms in the White House now.

End quote. Men all over Guadalcanal erupted in cheers like their favorite team had just scored a last-second touchdown at the Super Bowl. The whole thing was classic Tom. The former newspaper writer always knew how to craft a headline. During the chaos of the mission, Mitch's squadron became scattered, so all the pilots from the Yamamoto mission kind of straggled in one at a time. And the very first one back was Tom Lanphier.

Tom ripped his headgear off and leapt out of the cockpit, brown curls tumbling in the Pacific heat, white smile flashing for the ground crews to see. He looked and felt like a consummate star quarterback. From the second his boots hit the ground, Tom started saying over and over again, to anyone who would listen, quote, I got him. I got that son of a bitch. I got Yamamoto. End quote.

When the other pilots heard him take credit for the Yamamoto kill over an unsecured channel, they were horrified. First of all, there was no way of knowing for sure if Yamamoto was dead. There was no way of knowing if he'd been on board either of those bombers at all. The Admiral could be safely dozing in his quarters back on his flagship for all they knew. Not to mention, kills had to be confirmed. It was way too soon for Tom to take credit.

Mitch's entire squadron needed to be debriefed to compare accounts and testimony from each individual pilot. Half the squadron wasn't even back yet. But Tom was writing history in real time, taking credit for killing America's greatest enemy even when he knew he could not confirm it.

One pilot named Larry Grabener said that he thought to himself at the time, quote, Oh my God, what are you doing? End quote. And the truth was Tom's premature celebrations left a bad taste in many people's mouths. As a pilot named Joe Young said, quote, He claimed victory over Admiral Yamamoto in no uncertain terms. His reaction was astounding to me and appeared to be irrational. He was visibly shaken but very adamant about his victory. End quote.

A pilot named Roger Ames put it more simply, quote, End quote.

But most alarming of all was that Tom's specific reference to Yamamoto's White House quote over a hot mic was a dead giveaway that the U.S. codebreakers had cracked the naval code again. Tom's self-congratulation, if picked up by the Japanese, could put the entire Pacific strategy at risk. The pilots from Mitch's squadron returned to Guadalcanal one by one, and the very last man to touch down was Rex Barber.

His plane was full of holes, his fuel tank was running on fumes, and there were even scraps of the Japanese bombers embedded in his P-38's fuselage. Rex walked into the headquarters tent to find a huge party atmosphere. The whiskey was flowing, the songs were being sung, backs were being slapped, and at the shining center of it all was his friend Tom Lanphier Jr., repeating over and over again how he had shot down Yamamoto single-handedly.

Rex was normally a very calm guy. He didn't really ever get mad, as one colleague remembered. But something about Chatterbox Tom Lanphier basking in the glory of a momentous kill he could not confirm set Rex's blood on fire. Rex had shot down two bombers. The first one for sure, and the second with the help of another pilot, Besby Holmes.

Tom had been hundreds of feet above them, tangling with the zeros. How could he possibly have gotten either of them? As he seethed in the corner, Rex no doubt remembered he and Tom's chat back in Fiji, when Tom had told him about his goal of becoming President of the United States someday and how he needed to do something big during the war to make that ambition a reality. Eventually, Rex couldn't take it anymore, and he walked right up to his friend Tom in front of everybody and asked, quote,

How in the hell do you know that you got Yamamoto? Tom's big white grin faded. He was taken aback. Rex never talked like this, especially not to him. They were friends. But here he was, challenging Tom's victory in front of everybody, ruining his big moment. I mean, what was his problem? They were friends, sure, but who did he think he was talking to here? Tom answered Rex's question with pure venom. Quote, You're a damn liar.

Rex fired back, quote, but I haven't made a statement, I just asked you a question, end quote. Still, Tom kept being hostile, but eventually he took shelter in the reeds of ambiguity, saying, quote, as long as we live, Rex, we'll never know which one of us got Yamamoto, and that's the way it ought to be, end quote. Rex, disgusted with the whole thing, walked out of the tent to be alone.

The party was over. Later that night, Tom sat down at his typewriter. He flexed the old fingers that had hammered out articles and film reviews for the San Francisco newspaper, and he put his poet's mind to task. He decided to write an official, quote-unquote, report of the mission, something that would put his achievements in stone so that the likes of jealous Rex could never question them again.

He certainly didn't consult Rex, but he also didn't consult his commander, John Mitchell. Mitch had seen Rex and Tom's altercation, but said nothing. He remembered later thinking at the time, quote, End quote.

Well now, in the modern day, thanks to tireless research by journalists and historians and forensic analysts, we do know the answer to that question. Rex Barber is the man who killed Yamamoto. But his friend Tom Landfear is the man who took credit for it.

While the myth of Tom Landfear was being composed on a typewriter by Lamplight, a Japanese search party was hacking through the jungles east of Papua New Guinea in search of Yamamoto's plane. Japanese flight control had lost contact with Yamamoto's plane that morning and they feared the worst.

Survivors from the second bomber, the one that Rex and Besby Holmes had shot down over the water, had confirmed that Yamamoto had been in the plane that crashed into the jungle. Pilots from Yamamoto's Zero escort gave their superiors the approximate location of where they had been attacked, and a search party was immediately dispatched to find the commander-in-chief of the Japanese Navy. Or what was left of him.

On April 19th, a day after the aerial ambush, a member of the Japanese patrol started to smell the distinct chemical tang of gasoline wafting above the rot and the stench of the jungle. They followed their noses and eventually came upon the fresh wreckage of a Japanese bomber. Both wings had been torn off and the fuselage was shredded by fire from an American P-38, a quote, burned out Hulk, as one Japanese soldier described it.

There were bodies scattered all around the wreckage, men who had been lurched and heaved and tossed out in the process of a violent crash landing. But several hundred feet away from the crash, the search party found something very eerie. It was a single man, still strapped into his seat but very clearly dead. Somehow, he and his seat had been thrown out of the plane, landing perfectly upright amidst the foliage. To the casual observer, it looked like this guy was just quietly napping in a chair.

and members of the search party noted that the man had two wounds where molten bits of shrapnel had sliced clean through his body. The fatal wound had been delivered by a shard of metal entering under the jaw and exiting the top of the skull, a skull that was covered with close-cropped gray hair.

Then they noticed something else odd. The man was missing two fingers on his left hand. But it was an old wound, it wasn't caused by the crash. He was wearing gloves and the two fingers of the left glove had been tied up with a little string. It was clear that he'd been missing these fingers before he boarded the plane. And that little detail was a dead giveaway. They had found Yamamoto's body. The man who had planned Pearl Harbor was really dead.

Once Yamamoto's death was confirmed, the Japanese government sat on the information for an entire month. The public was not told. They were not ready for the psychological blow, it was believed. But eventually they couldn't keep a lid on it any longer. The Japanese people had to be told. On May 21, 1943, the news of Yamamoto's death was broadcast nationwide across Japan. The announcer had tears in his eyes as he read the following, quote,

In April of this year, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, met a gallant death on board his plane in an encounter with the enemy in the course of directing overall operations at the front line. End quote. Two days earlier, Yamamoto's lover, the geisha Chiyoko Kawai, had received a phone call. And the voice on the other line said, quote, "...I am very sorry to tell you this sad and unexpected news."

"Yamamoto was gone," they told her, and Shioko almost dropped the phone and fainted when she heard the news. She hadn't received a letter from Yamamoto in weeks. The last one she'd gotten had come with a small lock of his hair and a heartfelt haiku. And now, just like that, he was gone. To echo an earlier passage from Donald A. Davis, it felt like he had left a bar without saying goodbye. Like he had just vanished.

She could still remember him scooping her up in his arms and carrying her to the car on that long weekend they'd spent together just months before. In the immediate aftermath of Yamamoto's death, Chiyoko felt "bottomless sorrow." She felt as if "everything was finished."