Buried History: The Feminist Birth of the Home Pregnancy Test

Lost Women of Science

Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

Can we invest our way out of the climate crisis? Five years ago, it seemed like Wall Street was working on it until a backlash upended everything. So there's a lot of alignment between the dark money right and the oil industry on this effort. I'm Amy Scott, host of How We Survive, a podcast from Marketplace. In this season, we investigate the rise, fall, and reincarnation of climate-conscious investing.

Listen to How We Survive wherever you get your podcasts. This episode is brought to you by Progressive Insurance. Fiscally responsible, financial geniuses, monetary magicians. These are things people say about drivers who switch their car insurance to Progressive and save hundreds. Visit Progressive.com to see if you could save. Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. Potential savings will vary. Not available in all states or situations.

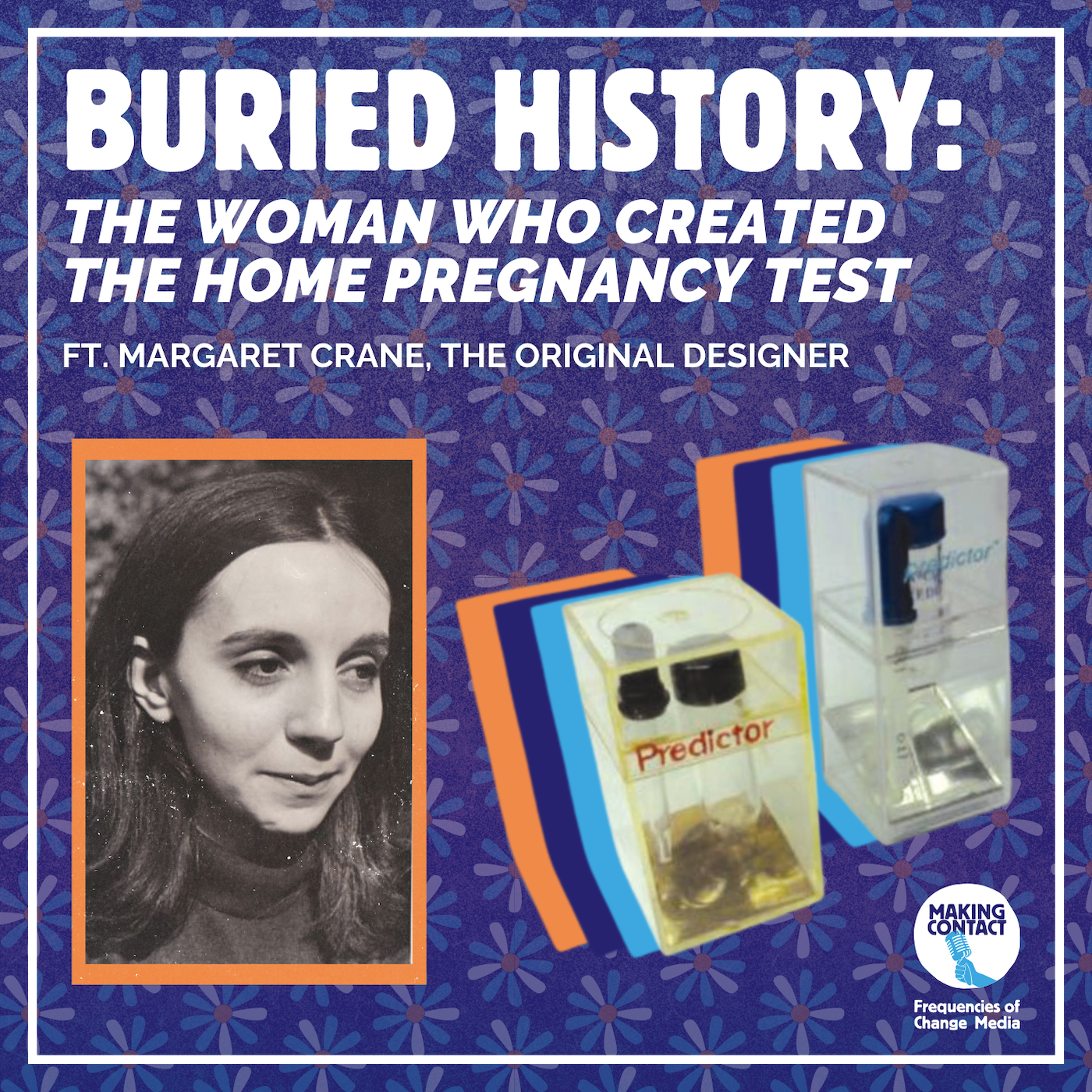

Hello, I'm Deborah Unger, Senior Managing Producer at Lost Women of Science. This week, we are bringing you a story from the radio show and podcast Making Contact. It's called Buried History, the woman who created the first home pregnancy test. Margaret Crane wasn't a trained scientist. She was a 26-year-old freelance graphic designer at a pharmaceutical company when she got her big idea.

At that time, pregnancy tests were only available at a doctor's office. Crane's contribution, like so many of the lost women of science we profile, was largely forgotten until about a decade ago. This piece was created by Making Contact in 2014 to celebrate Crane's ingenuity and to get her the recognition she deserves.

Crane is now in her 80s, and we're happy to remind everyone about the birth of her ingenious invention, for which she does indeed have a patent. Over to you at Making Contact. Making Contact. Making Contact.

I'm Amy Gastelum. Today on Making Contact, we're bringing you the birth story of America's first home pregnancy test. It was just amazing. I thought, well, how simple that would be. All you need is a test tube and a mirror, and a woman could do it herself.

That's Margaret Crane, she goes by Meg. In 1965, she was a graphic designer, only 25 years old. At that tender age, she got it in her mind that instead of asking a doctor for a lab test, people could do pregnancy tests at home. Just as a woman, I thought, why couldn't you know this yourself and not have some authority tell you this? That's coming up on Making Contact.

I'm Amy Gastelum. This is Making Contact. The story you're about to hear was produced back in 2014 with the help of our friend, reporter and producer Anne Noyes-Sanney. In this story, you will hear Anne and me repeatedly say women, referring to people who can become pregnant. Back then, we failed to include those who can become pregnant who don't identify as women. Since 2014, we've both adjusted our language, but we wanted to mark that former oversight up front here.

Okay, now to the show. This is where I work. It's my office. It's my... Oh my gosh. Best graphic designer, Margaret Crane. She goes by Meg. And we met in her apartment last year. It's sort of one of those cozy New York apartments where the living room and the dining room are the same room. And you go in the kitchen, you open the fridge, and it's the wall. So you go back into her bedroom, and there's this box taking up really precious space in the closet. And it's a really nice room.

And inside it, there are about 20 smaller boxes, like about the size of a smartphone. And those are the very first home pregnancy tests, the ones that came out in the 70s. And there's still some of the original ones here. So that's what they're like. And Crane has these because she designed them. Right. She's not just a collector of pregnancy tests.

And she has all these tests left over in that box, but really there isn't anything else in her apartment that identifies her as the inventor of this billion dollar industry. So no awards, no plaques, nothing. It kind of makes you wonder what happened. So Crane studied graphic design at the Parsons School of Design, New York City, famous school. But she left before graduating and started freelancing all over the place.

And in 1965, she went to work designing packaging for a pharmaceutical company in New Jersey. The company was called Organon, and Crane generally sat at a desk for her job there. But... Once in a while, I'd have to go over to the laboratory for some reason. So I was there, and there was an older gentleman there, Dr. Slade, who'd been there for many, many years. And he showed me these tests and how they were done.

This casual tour of the lab happened in 1965. Crane was 25 at the time, and she was the only woman in the lab that day. There were a couple of secretaries, you know, that the executives had. But it was, generally speaking, a very highly male-employed company. So she entered the lab that day, and she saw... A long line of test tubes and a, like, a metallic, um...

metal surface underneath them, angled underneath them. And someone explained that they were pregnancy tests. Okay, so at the time, a woman couldn't just go get a pregnancy test at a pharmacy or even at her doctor's office. In fact, a woman could only get a pregnancy test done in a lab like this if a doctor ordered it. And a doctor would only order it if there were something wrong with her pregnancy.

So back then, women basically just waited to see if they got big. And that's how they knew for sure that they were pregnant. Okay, back to the lab. And so all these rows of test tubes were different women and they're being tested for pregnancy or not. And looking at that, I thought...

It was just amazing. I thought, well, how simple that would be. All you need is a test tube and a mirror, and a woman could do it herself. Crane went home, and she started working on a model for a home pregnancy test. Her first attempt was based around this small plastic paperclip box that she just happened to have on her desk. Just as a woman, I thought, why couldn't you know this yourself? And...

You know, for all purposes, you know, if you were young married and wanted to find out, you know, what's going on here, are you pregnant or not? You know, why wouldn't you want to know that right away? And if you weren't married and were worried about what you'd have to do if you weren't, you'd still want to know soon. I mean, it's as simple as that. I'm just certain you'd want to know, period. You'd want to know yourself and not have some authority tell you this.

She worked on this project in her spare time. She was kind of obsessed. In fact, the night that she finished it was New Year's Eve. And that evening, Crane went to a party with friends. And I went like five minutes to the party and I just left the party and I spent the whole night trying to make this right. And that's when I finally finished the design on the test. And I brought it in and the man who designed

I brought it to him. He started asking me to call so-and-so. He thought I was his secretary, and so I was to, you know, do this or that for him. And he looked at it. He was sort of smiled at. I think he sort of, you know, sort of laughed and said, you know, that maybe somebody else could do this, but we can't.

So part of the problem was that these lab pregnancy tests were like half of Organon's business at the time. And the company, they weren't into taking crazy risks and compromising so many of their earnings by changing their whole business model. So marketing tests to women directly just seemed kind of crazy. That's right. That's true. But the other problem or problems were a little bit more tangled. The company wasn't sure how a test like this would be received socially because

or by the medical community? Yeah. So we have a friend, Jesse Oshinko-Grin. He's a researcher at the University of Cambridge, and he actually studies that. He studies the history of pregnancy testing.

And he actually, he pulled out this clip from a newspaper from England around 1969, which was right around the time that medical labs there started offering pregnancy tests that you could get without a doctor's prescription, which was crazy and revolutionary. And the doctors there, of course, were not happy. So here's Jesse reading that newspaper clip from 1969.

Women who apply for pregnancy tests to pharmacists instead of visiting their doctor may be risking their lives, the British Medical Association warned yesterday. So this is a radical statement. It's not coming from a kind of quack or a fringe doctor. It's coming from the British Medical Association.

I mean, this really does sound crazy today, but, you know, the article continues that women who are not happy about a positive result might do something drastic like commit suicide. And that pregnancy, moreover, was a too serious matter to be left to self-diagnosis and treatment. Okay, so we talked to Wendy Klein about this. She's a professor at Purdue University, and her work focuses on the history of women's health in the U.S.,

She did confirm that American doctors felt pretty much the same as their British colleagues. Part of the doctor's role is not only to provide medical care, but often with a moral tone that they're not simply dispensing advice or prescription, but they're going to let their patient know if they disapprove of the sexual behavior.

Did you have any personal experience with, but like before you were sort of working on creating your own design for the test, did you have any personal experience with any kind of pregnancy test? I'd never had to have my urine sent to a test, and I was lucky in that respect, I guess. But I certainly worried a few times whether I was pregnant or not, yeah. And if you had to go to a doctor as an unmarried woman and sort of go through the procedure for testing, like what...

How can you imagine what that would have been like for you at that time? A friend who had found a doctor who was very helpful to her sent me to a doctor who put me on birth control pills because he was very open to doing that. But not all doctors would have at that time.

They just came around in the early 60s and so not every woman was... You'd have to be married, let's say your doctor would consider they wouldn't give them to you unless you were married. This happened a lot. Why would you have to be married to have birth control? Well, guess. This is our society, right? So clearly you're not having sex if you're not married. Of course.

People really believed that. I guess they hoped that maybe if they came from a certain background. I think the state of Connecticut at that time still could not sell birth control in the entire state. This is in the 1960s. And this happened in other states. It wasn't readily available, period, period. Yeah.

Remember, women's reproductive stuff was really hot in the 1960s. In Great Britain and the U.S., the pill and elective abortion were fiercely debated. Jesse told us non-medical pregnancy testing was debated right next to these issues. Pregnancy testing was really bound up and caught up in much broader debates around women's rights, women's control over their own bodies, around reproduction, abortion, and contraception.

Wendy Klein, that professor you heard before, she said women were rallying around these reproductive issues because they were seen as the most basic rights, rights over their bodies. This idea that they could understand and have information about what their bodies were doing without somebody else telling them that their bodies were doing it was...

literally a revelatory moment because it meant individual women could have more control over their reproductive lives and thus their lives more generally. So for women at the time, there was so much at stake and also a lot of pushback from churches and doctors. And that is the climate in which Meg Crane tried to make a home pregnancy test.

And that's, you know, just what was going on outside the company. Inside Organon, it really wasn't much better. So we talked to this guy, Arthur Cover. He's one of Crane's old coworkers. And back in the day, he worked in advertising and Organon was one of his accounts. What was Meg like? She was very pretty. She's very self-effacing, very quiet. And she also is very talented, as we found out later.

Arthur admits women weren't treated all that well at Organon, but then again, they weren't really treated well anywhere at the time. Even I, a chauvinist male, cringed at some of the stuff that went on, especially in the ad business. So not just Organon, but just generally in the business world at that time, the way women were treated? Yes. Women were treated as either processors of data,

or potential sexual predatees. That's gross. So given that, it's not really all that surprising that the bigwigs at Organon didn't really take Crane or her idea very seriously. But she didn't give up. And after she was told no, Crane kept pushing. And finally, one executive actually listened a little bit.

And at one point, one of the executives went to the parent company in the Netherlands for a meeting, which they do pretty often. And he came back with some funds for it because he brought it up to the Dutch and they were so...

you know, advanced in that way. Crane says the Europeans were a little bit more progressive about reproductive stuff. In fact, they already had a similar home pregnancy test in the works over there. So they gave that executive some money to get it started here in the U.S. And that's when they hired other designers to create prototypes for a home pregnancy test. Yes, the test Crane had come up with and built and pushed so hard for.

And there was to be a meeting in the conference room where these people would be showing their work. And I was allowed to be in that meeting. So they put their work on the table and at the end of theirs, I put mine. Organon invited their new advertising team to this design meeting, including Arthur and another ad guy named Ira Sturdivant.

And he walked in, walked down the table and picked mine up and he said, "Well, this is what we're using, isn't it?" And an executive said, "Well, no, that's just something Meg did for talking purposes." At that point I thought, "Whoa." So, yeah, from then on I kind of realized I wasn't really going to be getting much credit whatsoever for it.

but did they end up using your design? Sure. Yeah, they did. They had, as a matter of fact, they said, uh, because the, the other designs are really not good at all. They weren't scientifically right. They weren't, you know, they were very feminine looking little things you would get bobby pins in or something. And, um,

I'd asked about producing mine, and they said, well, yours would be much too expensive. It's very elegant. That's for the wealthy woman. And so I took off from work, and I went around to plastic companies in the Bronx and Newark and all kinds of places. And I finally found a company that came in with a price that was so much less than any of the ones the other designers worked. So they had to do it. I think that's how it happened.

Eventually, the company also thought it was the right design, and they bought the patent from Crane for a dollar. They had a little signing ceremony in the outer lobby in the offices and had all the paperwork there for me to sign. And I signed my rights away. I was to get a dollar for that. But I was just very thrilled that they were going for the patents, which I couldn't do myself. I couldn't afford to do it. So, yeah.

I was compensated later because a company came to my husband and me to do the test market in Canada. So that was, we got paid for that. That's right, folks. It started in Canada, not the U.S. But first, remember that other ad guy, Ira Sturdivant, the one who walked in and grabbed Crane's design? Well, there's a little bit more to that part of the story. ♪

When he walked in that day, I just, I fell in love with him at that moment. And we hadn't met yet. And I came home and told my roommate in New York that I'd met the man I was going to spend the rest of my life with. That's what happened. The rest of his life, certainly. And then we started working together. That was January. And by July, we were living together. Yeah.

They rolled out a marketing campaign for the first home pregnancy test. That was in Canada in the early 70s, and they called it Predictor. But right away, they hit some bumps.

Some ministers across Canada got up in their pulpit and just said how terrible this was and another shade of evil coming into women's lives to be able to do this. I mean, we got really nasty letters from people too. But for the most part, we got some good press. Some of the letters that came back were women saying how thrilled they were to do this themselves.

Eventually, the test made its way to the U.S., and the rest is history. By the way, we did reach out to Organon's current parent company, which is Merck, to get their side of the story, but they declined to comment. You're listening to Making Contact. Just jumping in here to remind you to visit us online if you like today's show or want to leave us a comment. We have more information at radioproject.org. And now, back to the show. ♪

At this point, Meg Crane had come up with the idea for a controversial, revolutionary product. She designed a prototype for it. She sourced materials for it. And she rolled out a marketing campaign for it. And at this point, she's not even 40. What have you done with your life? Can you compare? Yeah. Anyway, so after the marketing campaign, the test caught on here in the United States. Big time, right? Yeah.

Yeah. Now they're everywhere. You can go in any pharmacy and get a pregnancy test that you can take by yourself in your bathroom or wherever you want. No big deal. Yep. It's very convenient.

And it made a lot of money, made a ton of money. It's like $1.68 billion of pregnancy tests are sold globally each year. Damn. Wow. Yeah. It's insane. It makes a ton of money. And it also changed the way that women learn about their pregnancies, obviously.

But, and here's the but, but Margaret Crane, she never really got any credit for her work. Which is crazy, right? And it's not like there weren't opportunities to give her credit. I mean, a few years back, the National Institutes of Health put together this really comprehensive history of the pregnancy test. It started in 1350 B.C.,

1350. That's right. 1350. 1350. Pregnancy test in 1350. What's that look like? You know, I don't remember. I think it was like peeing on like sand or something. I don't know. Peeing on sand. And it went from 1350 BC all the way up to 2003, which is when Clear Blue Easy's digital home pregnancy test came out. And in that whole timeline, not a single mention of Crane. That's terrible. Yeah.

Yeah, right. But then in 2015, that prototype she made with the paperclip box, it was put up for auction. Margaret Crane, first home pregnancy test there is. Before the bidding started, a rep from the auction house asked Crane what she wanted to earn from it.

I said, again, how do you put a value on something like that? And she said, well, $5,008. And I said, well, how's six to nine? Because Ira's birthday was November 6th and mine was the 9th. So that seemed like the only way to do it. Any more? $9,500. I can and will sell at $9,500. Tom, are we out at $9,500? Last call at $9,500.

It sells to you, Christina, 4660. The Bayer was the world's largest museum complex. That's right. Now Crane's invention lives at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. So we're going to walk down the hall to our storage room. Alexandra Lord is the chair and the curator of the museum's History of Medicine and Science Collection. She is now the keeper of Crane's prototype.

And Lorde wears these white rubber gloves while she carefully removes it from the humidity and light controlled cabinet where it's stored now.

And if you look at it, it's not very sexy to look at. In many ways, it's very simple and straightforward. It's basically just a plastic box with a mirror on the bottom, an angled mirror, and two test tubes. And it was very simple to use. It actually took just a few hours. And the predictor and the company which produced the predictor claimed that you could have this...

probably within about four or five days of being pregnant, you could actually make a determination. And since most doctors and most patients didn't go to the doctor to determine whether she was pregnant or not until she had been pregnant for several weeks, this was just a major breakthrough in how early a woman could learn about her pregnancy.

Second, it's a really interesting comment on how someone who's not a scientist, Margaret Crane was a graphic designer, can play a major role in getting a scientific product into the hands of the general public.

Remember Jesse O'Shinkle-Gren, the researcher at Cambridge? He says that without Crane, we may never have gotten a home pregnancy test in the U.S. Or, at the very least, we would have waited a lot longer. You know, the science was sitting around for a decade, you know, before Meg turned it into a home test. I mean, just because the science is there doesn't mean it's going to be used by the people that need to use it. I really think the...

I really want to emphasize that it's not like the design is an optional add-on to the science. I mean, I really think without the design, the science was nothing. It didn't make home pregnancy testing by itself. It really did need the design. Remember Arthur Cover, the ad guy who worked with Crane at Organon? The first time he saw her prototype, he says he knew it was special. It was dynamite.

Dynamite in a bad way. Well, you know, dynamite can be used to construct dams as well as blow down buildings. I could predict the fact that it would create a need that was always there but had never been crystallized. That's the thing. It's sort of like something like this crystallizes a need that people aren't really aware of.

Okay, well, let's be honest. Clearly, some people were aware of this need. I mean, it seemed really obvious to Crane, right? It did. It seemed really obvious to Crane. And maybe that's the point, right? Yeah. Like maybe any woman would have walked in there and been like, this is really obvious.

And women and people of color are still way underrepresented in science and engineering. Yeah. And maybe, maybe if more labs had more people with different perspectives, they'd be able to figure out how to create the next billion dollar industry. You know what I mean? Yeah. Amy, I got to say, does this sound familiar to you at all?

It sounds very familiar. You know, here we go again. A woman with a great idea works her ass off to make it happen. And then she gets no credit, no money, nothing. You know, everybody else benefits, including a bunch of people that don't really deserve to benefit. I mean, let's be honest. We benefit. We the women who use the pee sticks. I do. Thank you. Thank you, Margaret Crane.

Good for us. Thank you so much. But also all those pharma guys that made billions and billions of dollars, they benefit a lot, probably more than us in some ways. And Meg, she's the mother of this industry. She made this industry possible because all those guys didn't understand the importance of selling to women. And she did. Thank you.

Did you have a sense this changed things for women first in Canada, but then eventually in the 70s when it came here, how it changed women's lives? I remember being at parties or groups of people and a woman saying, for instance, oh, I just took the pregnancy test and, you know, John and I are so thrilled or whatever, you know, things like that. I heard a lot of people saying they'd taken them. They didn't know that I was involved with them. So that's just kind of fun to hear that and

And young women that I did know who knew that I was working on it told me what it meant to them to take the test. So, yeah, I think now I'm very proud of that. I'm very happy that that happened and I had part of it. And has the company ever sort of acknowledged or credited you in any way that isn't financial? No, no. People didn't know I've done this and...

You know, I don't want to go bragging about it. You know, I just, it was very, very hard to keep it back. Sometimes I do want to tell people, and I know this has been done and it's, you know, Smithsonian has it, but I have to be careful. When the auction was sort of announced and publicized and journalists started coming and asking for interviews, was that the first time that anybody had sort of come to you and acknowledged your work and your contribution? Yeah, yes, it was.

Nobody knew really, would have reason to know. You know, that's... Did it feel like almost anticlimactic after so long? Or did it feel like, yes, this is appropriate? It's both. That's crazy. It does seem anticlimactic in some ways. Because I wish Ira was here for this. I really do. That's part of it. And...

And I'm grateful for my family to pushing me to get something done on this. I really think it had to be, and I'm 75 now. I should do something now with it before it's, you know. And so I'm glad it's done. I'm glad it happened. And even for whatever credit is coming down this way, it's fine. I'm Amy Gastelum. You've been listening to Making Contact. For more information, visit our website, radioproject.org. Until next week.

Hi, I'm Katie Hafner, co-executive producer of Lost Women of Science. We need your help. Tracking down all the information that makes our stories so rich and engaging and original is no easy thing. Imagine being confronted with boxes full of hundreds of letters and handwriting that's hard to read or trying to piece together someone's life with just her name to go on. Your donations make this work possible.

Help us bring you more stories of remarkable women. There's a prominent donate button on our website. All you have to do is click. Please visit lostwomenofscience.org. That's lostwomenofscience.org. From PR.