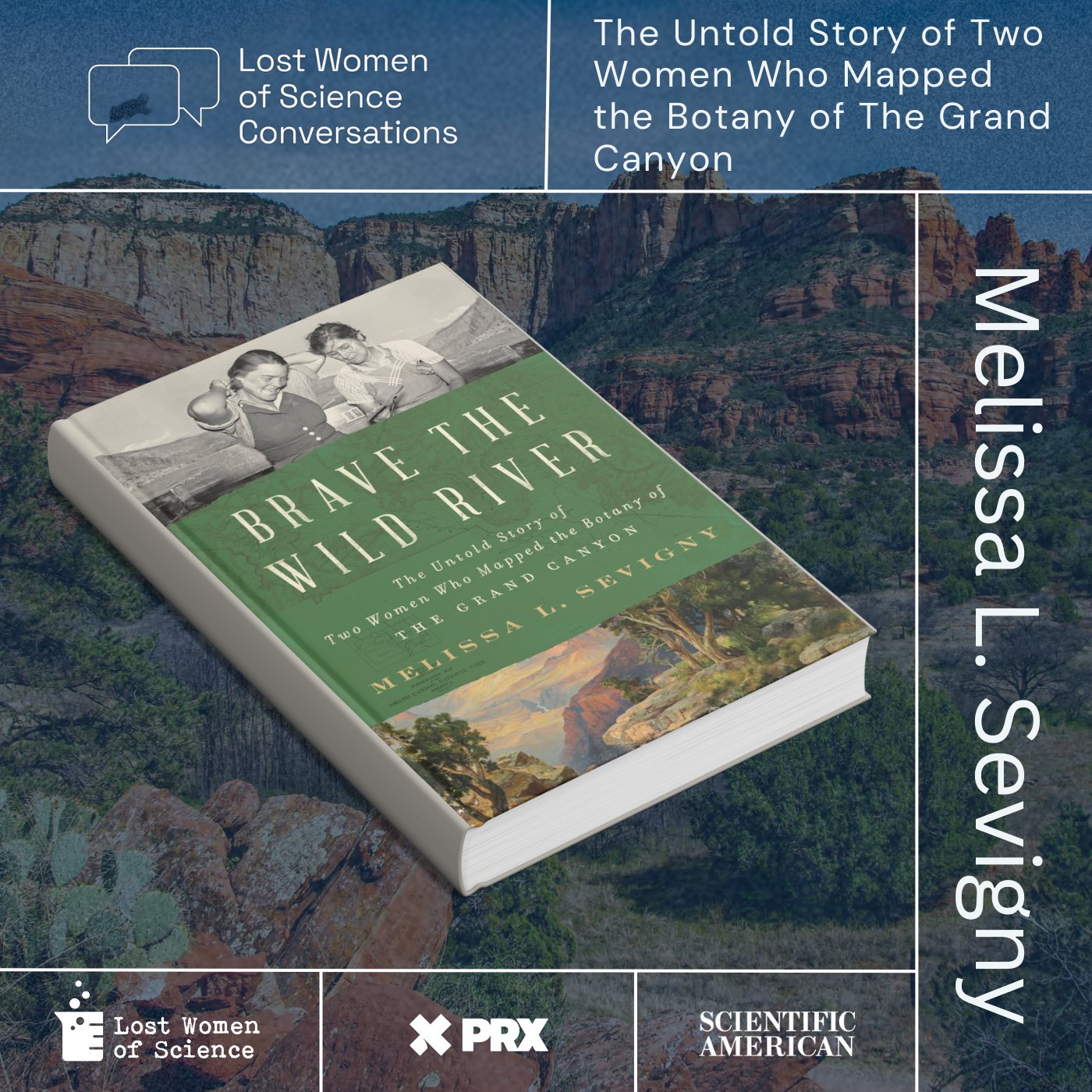

Lost Women of Science Conversations - Brave the Wild River

Lost Women of Science

Deep Dive

- Melissa Sevigny discovered Lois Jotter's papers at an Arizona university archive.

- Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter were botanists who made a significant expedition down the Colorado River in 1938.

- Clover was older, ambitious, and obsessed with plants; Jotter was younger, bookish, and more laboratory-focused.

Shownotes Transcript

This episode is brought to you by Progressive Insurance. You chose to hit play on this podcast today. Smart choice. Make another smart choice with AutoQuote Explorer to compare rates from multiple car insurance companies all at once. Try it at Progressive.com. Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. Not available in all states or situations. Prices vary based on how you buy.

None of them have ever done a trip like this. And they leave in the summer of 1938 at very high water. It's monsoon season in the desert. There's these enormous waves in the rapids, these big whirlpools, these rocks they have to dodge. The water's moving very quickly. And they're completely unprepared for that. You know, their first sight of the Colorado River. And their journals, they all talk about how they're just standing there staring at it thinking, like, what have we gotten ourselves into?

Hi, I'm Carol Sutton Lewis. Welcome to the latest episode in our series, Lost Women of Science Conversations, where we talk with authors and artists who've discovered and celebrated female scientists in books, poetry, film, and the visual arts.

Today, I'm joined by Melissa Sivanyi. She's an award-winning science writer and reporter based in Flagstaff, Arizona, and her latest book, Brave the Wild River, the untold story of two women who mapped the botany of the Grand Canyon, won the National Outdoor Book Award and the Reading the West Award, among other honors. The book combines a biography with a gripping river adventure and a close look at the science of botany.

In the summer of 1938, two botanists, Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter, made headlines for being among the first women to ride the Colorado River. But as Melissa writes, they accomplished much more than that. They documented important plant life in the Grand Canyon, which contributed to a major shift in the practice of botany. Melissa's book gives them the credit they deserve, and with vivid writing, she tells how they risked their lives in the expedition.

Melissa, thank you so much for joining us. I'm so happy to be here. We are so happy to have you. So, Melissa, let's start by finding out how you discovered these remarkable women, Elzada Clover and Lois Jodder.

How did you find them? It was really quite by chance. I live in Flagstaff, Arizona, not far from the Grand Canyon. And there's an archive at the university here that has all of Lois Jotter's papers. And I just stumbled across it one day. I was looking for something entirely unrelated. And I ran across this hyperlink online where I was searching that said women botanists.

And I was curious, so I clicked on it, and there was just one name in the record, and that name was Lois Jotter. And I read the description, and I learned that she had gone on this grand adventure in 1938 with her mentor, Elzada Clover, and that all of her letters and her diary and a bunch of other information was filed at the university. So I started kind of popping over there like on my lunch break and just poking around and looking through this record, and

And the more I read, the more I just thought, wow, this is a really extraordinary story. And I was really surprised I had never heard of it before. You know, I grew up in Arizona. I thought I knew a lot about Colorado River history. And yet I had never run across their names. And so the story just kind of drew me in. And so tell us a little bit about both of them, a little bit about their early lives. They were good friends, and yet they were very, very different people.

That's right. Yeah, they were both quite different. They were separated by about a generation in age. So Alzada Clover was the older of the two. She was 41 years old at the time she went on this river trip. She had been born kind of right at the turn of the century on a farm in Nebraska.

and really born into a world where she was supposed to get married and have kids, and that was going to be her life. And it's pretty clear that's not what she was interested in doing. She wanted to have a career of some kind. And so she ended up in Texas. She was working as a schoolteacher there.

And sometime while she was in Texas, she really fell in love with desert landscapes. She fell in love with cactus in particular. She decided she wanted to make a complete collection of all of the cactus in the Southwest. So she was an ambitious woman. She made her way to the University of Michigan. She got her PhD in botany. She was kind of like a big character, a big personality. People who knew her described her as sort of larger than life. She would sail into a room and just kind of fill up the space.

and just obsessed with plants. That was her entire life, was...

going out into wild places and picking up plants. I tracked down some of her students and they said they just absorbed that passion from her by like osmosis, you know. And I think one of those students was Lois Jotter, who picked up on her obsession with plants. But Lois was quite different. She was a generation younger. She was 24 years old. She had been born in California among the redwood trees. She had decided at a very young age that she wanted to be a botanist. And

And so at the time of this river trip, she was working on her PhD at the University of Michigan. But she was doing kind of different work than Elzada Clover was. She was doing more laboratory-based work, genetics-based work. She did have quite a bit of like outdoor camping experience, but she didn't describe herself as an adventurous person, not like Clover was at least.

She described herself actually as bookish and a bit of a klutz. So for her, I think it was a little outside of her comfort zone to go on a big grand adventure. But like Clover, she was obsessed with botany and she really wanted to make her mark on the field. Now, Clover is the person that first had the idea of this expedition as a scientific expedition.

And you've said that she was really enthusiastic about botany, but why did you think that she wanted to take on this particular expedition? Yeah, she kind of cooked up this plan. It felt to me like a little bit of a last minute way. You know, she's collecting plants out in Utah in 1937, and she meets up with a guy who has an idea of starting river running trips through the Grand Canyon, which

which nobody is doing. You can't just sign up and go on a river trip through the Grand Canyon. Like it's this really wild, inaccessible place and kind of scary for boating. And the two of them just get to talking and she thinks, this is it. This is what I can do. Because I think I imagine her kind of looking around the country and thinking like, where can I make a mark on botany? And the Grand Canyon is this sort of

blank space on the botanical map. Like nobody's gone down the river in the Grand Canyon and collected plants. Nobody's surveyed the plants because it's really hard to reach. And so she's looking around thinking about like, where can I do something that will make a difference? And she sees this blank space on the map. And she decides like, that's what I'm going to do. I want to go down into this very deep, inaccessible canyon and make the first ever formal plant survey there.

Now, that sounds ambitious, but not particularly spectacular to us now. But back in her day, that was pretty much unheard of in terms of women making that trip. And her interest in doing this was also at a time when the field of botany was really changing. Can you tell us a little bit about that, about the shift in botany that we were seeing?

That's right. Yeah, the field of botany was changing fast in the 1930s. So Elzada kind of came from the old school of botany, where the work was taxonomy, right, which is the science of going out and collecting things and naming them. So that's really what people were busy doing in the 1900s and kind of 1910s is just collecting.

collecting plants and naming them. And this was very welcoming to women, actually, which surprised me when I learned about it. But the idea is basically you're collecting flowers, right? And that seemed like a very acceptable activity for young women to do, as long as they didn't go anywhere too far away or too dangerous, and they didn't come back with their clothing torn up or anything like that, as long as they kind of kept it safe.

it was very acceptable for women to do this work. And the idea is they would collect the plants and they would send them to a botanist at universities to do the formal classification work. And so this was kind of the field that

Jose de Clover was doing. But in the 1930s, things had started to change and botany was becoming a much more laboratory-based science. It was kind of moving into a professional realm. It was moving into the universities. That was the kind of work that Lois Jotter was doing, right? She was doing like early genetics research and

And as that shift happened, the field became much more inaccessible to women, right? As it became a more professional science, it became a more masculine science. And so these two women were working at a really interesting time. It was unusual for women in the 1930s to get PhDs in anything, let alone in a science field. And they were really kind of swimming upstream in order to achieve what they had achieved. So in your research,

Did you find that Clover had a particular hypothesis about the unexplored area? Or I know that she had a fascination with cacti. Did she expect that there would be species that she hadn't found yet? Or was she really just anxious and eager to explore what could be there?

I think it was the latter. I think they kind of went into this with the idea that she wrote this actually in an application for a grant. She said, anything we find will be interesting because nobody has ever botanized this area before. So they went into it with this really open mind of like, whatever we pick up is going to be interesting. And I think they weren't so fixated on the idea of finding or identifying species that were new to Western science so much as kind of

essentially making a metaphorical map of where plants were growing in this area. They knew it was the meeting of three different types of desert, all with their unique kinds of plants. And so they wanted to see how those deserts met and mingled. They knew that as they went down the river, it was more than a 600 mile trip they were taking through Utah and Arizona to

As they went down those 600 miles, they would be going down in elevation and they wanted to track how plants shifted as the elevation became lower and the climate became drier and hotter.

Even today on a river trip, you can see this if you're paying attention. All of a sudden you're going along and there's barrel cactus where there weren't barrel cactus before. You can see these shifts happening. But of course, in their era, they didn't know that yet. Nobody had seen this in action or documented it in action. So they really went into it with this very open mind of whatever we find is going to be important for science. And as you discovered this story and decided to write about it,

Was your perspective that this was more of a story about science or more of an adventure story or really a combination of the two? I went into it as a science writer, really wanting to write about the science, particularly

I felt that way because not very many things had been written about these women before my book came along. And those things that I did read about them were very focused on kind of the adventure aspect. You know, they talked about it as being these were the first non-Native women to make this journey. And that was really kind of the focus on their gender and on the unusualness of them doing this trip in the 1930s and the kind of high drama of the Rapids.

And all of that was interesting to me, but I felt like the science story had gotten left out. You know, their work as botanists had gotten left out. And that's really what I wanted to write about going into this story. Of course, the adventure is there and it gets mixed in as you go. I wanted it to be a page turner. So I'm hoping people who aren't necessarily interested in science will pick it up for the adventure and they'll get a little bit of botanical science along the way. Yeah.

It truly is a page turner. It definitely is, and I thoroughly enjoyed it as such. But it was also fascinating to...

Sure.

Sure. Yeah, it was an uphill battle for me. I'm not a botanist myself. My undergraduate degree is in environmental science. So, you know, I had kind of a foundation there. But I didn't actually know a whole lot about botany going into the project. And mostly I relied on botanists around me. I emailed people a lot of questions and there were a lot of very kind botanists who answered very specific questions about cactus plants.

And I had a lot of fun writing about the plants and choosing which plants to write about. You know, they cataloged hundreds of plants on this trip, and I could only highlight a few. And so I tended to sort of gravitate towards the plants that I knew well. You know, I grew up in Arizona running around wild in the desert. And so many of these plants I didn't know as a botanist, but I knew as just, you know, I knew their personalities, you might say, as someone who grew up in the desert. And so I had a lot of fun writing.

Choosing which plants to write about. And yes, I had to give the Latin names because there's so many common names of plants that it gets confusing if you don't get really specific.

Now, I want to ask you, I know that it is a science story, but it definitely is also an adventure story. And I want to ask you about the actual trek. So when these two women set out to run the Colorado River, which for those of you who are not familiar with the jargon, that means to take a boat and float down the Colorado River in the summer of 1938, it was considered one of the most dangerous rivers in the world. And

The only other non-Native American woman who had attempted the trip disappeared and her body was never found. Can you tell us a little bit about...

what made the trip so hazardous? What were the conditions that made it so difficult? That's right. Yeah, they're going on this journey starting at Green River, Utah and going through a series of very deep canyons, Cataract Canyon, Glen Canyon, and then the Grand Canyon. And one of the things that made it so hazardous was just how inaccessible it was. Like even today, once you're down in those canyons, there's no easy way to get out again if you get into trouble.

And another thing that was quite difficult was, you know, in the 1930s, they didn't have all of the kind of equipment we had today. They didn't have the big rubber rafts that you normally take down the Colorado River today. Instead, they were in these handcrafted wooden boats that were sort of a newfangled design. They didn't have really good maps about what was coming up around the corner. No emergency equipment, no radio to call for help. Really no one who would come help them, even if they did have a radio. They're really on their own once they get on the river.

There's a couple of spots where they can stop and contact the outside world, but for the most part, they kind of disappear into these canyons and everybody outside is holding their breath, waiting to see if they're going to come out again with really the expectation that they wouldn't. The newspapers at the time are very fixated on the idea that they were going to smash up and this trip was going to be a disaster.

Another thing that made it really hard was that none of them had any experience with whitewater river rafting. There's six people on this expedition in all. Three of the men are supposed to be the boatmen who are rowing the three boats. None of them have ever done a trip like this. They have no idea what they're getting into. And they leave in the summer of 1938 at very high water. It's monsoon season in the desert. There's these enormous waves in the rapids, these big whirlpools, these rocks they have to dodge. The water's moving very quickly.

quickly. And they're completely unprepared for that. You know, their first sight of the Colorado River when they come down the green for a couple of days and then they hit the confluence with the Colorado River and their journals, they all talk about how they're just standing there staring at it thinking like, what have we gotten ourselves into? Oh my goodness, I can only imagine. And we'll find out what happens next after the break.

Marguerite Hilferding basically created the field of psychoanalysis that Freud and Jung credited in their papers, yet no one's heard of her. Dr. Charlotte Friend discovered the Friend's leukemia virus, proving that viruses could be the cause of some types of cancers. Yvette Cochoir discovered the element astatine and should have won the Nobel Prize for that.

Is there a lost woman of science you think we should know about? You can tell us at our website, lostwomenofscience.org, and click on Contact, where you'll find our tip line. That's lostwomenofscience.org, because it takes a village to tell the stories of forgotten women in science.

The leader of the expedition was a river runner who wanted to become the Grand Canyon's first commercial river guide. And there was a zoologist and a photographer and an engineer. And everyone else in the boat had different goals for the trip, from the entrepreneurial to our protagonist had scientific goals, of course.

How did these different objectives come into play while they were on the river? Yeah, it turned out it didn't all play very well together. You know, the leader of the trip, Norm Nevels, has this very business-minded idea, and he's interested in drumming up a whole lot of publicity and getting a lot of attention.

And also in making Colorado river rafting seem safe, right? If he wants to start a commercial river trip and get people to sign up and pay him money to go down the river, he needs to convince people that it's safe, which was not what people thought about it at the time. And I think this is why he was willing to bring women along on the trip. It was very unusual for any kind of adventurer in the 1930s to welcome women on an expedition. And I think in Norm Neville's mind, he's thinking,

If I bring women, what better way to make it seem safe, right? Even women can do it, right? So this is his motivation. And this does not play so well with Clover and Jotter's motivation of doing scientific research. And when they get on the river, they discover that

They're going to spend a lot of time just trying to get the boats downriver and stay alive, and there's very little time to do the scientific work that they wanted to do. And on top of all of that, they're also in charge of all the cooking for the expedition. There was no discussion about this in advance, right? There was no agreement that they would do the cooking. It just, that's how it turned out because it's the 1930s. The women have to do the cooking. And so they're very busy and they're very tired and they're getting up quite early and they're staying up quite late trying to do their plant collecting. Yeah.

And, you know, at their stops, when they see what the newspapers are writing about the trip, they start really getting upset with the publicity, which is very focused on the fact that they are women and says almost nothing about the fact that they are botanists.

And so it becomes a frustration and there's a lot of tension between the crew members as they go down the river on, you know, just having really different ideas about what this expedition is about. And you detail that all so well in this book. Now, let's talk a little bit about the women's contributions, their scientific contributions. And first, the logistics of it all. How did they manage to collect and document hundreds of plants?

during this journey, how they keep them dry and safe while they're on whitewater rapids. I mean, it sounds so difficult. Really, really difficult. So they were creating plant presses as they moved down the river. So they were cutting plants and they were pressing them between newspaper, putting blotting paper around that to try to keep it dry, and then putting the whole thing between two pieces of wood and cinching it tight. And they were keeping these plant presses in the supposedly waterproof hatches of the boats

The first time they upset a boat, they discovered the hatches are not so waterproof. And so I think the answer to how they kept them dry is probably they didn't keep them very dry. I think that was a frustration for both of them as they moved down the river, that it was hard to get really good quality specimens.

And yet, despite those challenges, they did manage to collect and catalog hundreds of species on the 600 mile journey. And I think they did that with a lot of very hard work. You know, one of them would cook dinner and the other one would go off and collect plants and then the next night they would switch places.

They stayed really focused on getting those plants and making notes. They made incredible notes about what they were seeing, what they were observing as they moved down the river. And I was really fascinated by those notes because 1930s, there's no conception of an ecosystem yet, right? Like the word ecosystem had been invented in 1935, but nobody was using it yet.

And so our modern ideas of like how plants and animals and soil and topography and climate and all that stuff works together, there wasn't really a conception of that in the 1930s. And yet they're making notes about all of those things as they move down the river. They're making notes about how plants adapt to survive in a place where there's severe droughts and big floods and landslides.

Today, we would call that ecosystem science. But at the time, they didn't really have that conception. You could see them sort of moving towards it in the observations they were making. Melissa, this book is so immersive, and it's packed with so much vivid detail, both, as I said before, of the plant specimens they were finding, but really of the adventure of it all. And it's almost as if

We are in the boat. You have put us in the boat with the women. What inspired you to approach it this way? And how did you manage to do that, to help us experience this so vividly? I didn't know I was going to write it that way at the beginning. Again, coming at it with the idea of being a science reporter and having a lot of kind of information I wanted to convey.

My first draft was a real mess because I was trying to cram so much in there about, you know, how the Colorado River has changed since the 1930s and the dams that have gone up and the non-native species that have come in. And I ground to a halt trying to write it. It was terrible. You know, it didn't work at all. And I had kind of an aha moment where I was looking at this timeline I had put together of all these major events on the Colorado River. And I realized that I needed to keep myself and the reader focused

in Clover and Jotter's heads, right? I couldn't talk about anything that happened after 1938. I had to stay in the moment. And I went back to the beginning and I started rewriting all over again, making sure that everything in the book was 1938 or earlier. Even the metaphors I used. At one point, I used a metaphor about a reservoir sucking up a waterfall like a vacuum. And I went and I Googled and made sure that vacuums were around in the 1930s because I didn't want to take the reader out of the moment.

And another thing I did to really help myself write vivid scenes was I ran the Grand Canyon myself. I had never done anything like that before. Like Lois, I'm not that adventurous. I'm sort of bookish and I like being home. And so this was a little scary for me, but I signed up to go on a botanical expedition there.

down the Grand Canyon. We were weeding plants out of the Grand Canyon that don't belong. And I kept a detailed diary on that trip. And when I got back, I pulled descriptions of the geology and the experience of being down at that canyon. And I...

I typed them all up and printed them out and taped them into my draft, and I sort of wove them into the story so that the reader could feel like they were there. Wow. No, you really do feel that. And I have to just add, because I was delighted to see in your epilogue that not only did

did you run the river as Clover and Jotter did, but you actually had a little piece of their trip with you. I did. Yeah. It's sitting on my windowsill right now, the little match case that Lois Jotter took down the river, which was gifted to me by her son, which was a really wonderful moment. And I took that with me. I kept it in my pocket, zipped up the whole way because I was so afraid of falling out of the boat and losing it. That's great. I want to hear a

I want to hear a little bit more about your actual research for this, though. I mean, because you convey what was happening, again, with such specificity and such realism. What did you rely on in terms of being able to know what they were thinking? There were journals. What other kind of reference...

materials did you use? Yeah, the diaries that both women kept were really, really invaluable. I'm lucky that they kept detailed diaries amid everything else they had to do and that they had the foresight to donate those diaries to archives before they passed away. I was really careful not to make assumptions about what they were thinking or feeling on the trip because sometimes it overturned my own assumptions. There's moments where I thought in that situation I would be terrified and

And Clover and Jotter would write in their diary, oh, it was such an adventure. We were having such a great time. So I really relied on their diaries for kind of that internal thought processes that they were going through. They also wrote a lot of letters, and I tracked those down in various archives. Every time they had a chance to post a letter, they would write back to their friends and family back home.

That was kind of the heart of the story, but then outside of that, I pulled in a wider range of references, letters from other river runners who were writing about this trip, oral histories that were done later on, photographs. There's even some film footage. Elzada Clover brought a camera with her and took some film footage, and so I tracked that down and watched that, which really gives you a sense of how big and how terrifying those rapids were and these tiny little boats are bobbing along there.

And then probably one of the most important references was actually finding people who knew them. Of course, both of these women have passed away and I never had a chance to meet either one.

But I tracked down some relatives and some former students of both of them. And that was really important for really understanding who they were as people, kind of figuring out their personalities and their motivations. So I'm really lucky I was able to find some folks who knew them who were willing to describe to me their experiences with these two women. So early on in the book, Jotter's father, who supported the expedition emotionally and financially, although he worried about her incessantly while she was on it,

He warned her that the river will change you. That's what he told her. And to assure him that she'd be fine, she wrote him back and said, when we come out, I'll still be me.

But it seems in your book, the river did change these women. How do you think that they were changed? That's such a great question. And I thought a lot about it when I was writing the book, because when I ran across that moment, you know, I knew right away that she was going to come out changed. I don't think you can do an expedition like that, even in the modern day, without coming out changed. I think in a couple of ways, I think both women felt that they had made a mark on the field of botany.

And they had to hold tight to that because when they came back, a lot of their colleagues did not feel that way. They were getting a lot of kind of a hard time from their colleagues, from the newspapers that covered the expedition, saying that they had just been daredevils and they had just wanted to go on this big adventure and not really getting the respect for the work that they did. And yet I could tell they were both really for the rest of their lives holding tight to this idea that they had done something significant, right? They had filled in the botanical map.

in a way that mattered to science. I also think there's something that's a little harder to describe that happens when you come out of a place like the Grand Canyon. You do come out changed, and I think it's because you spend, in their case, more than a month

in a place where you're living very much in the present moment. You're thinking about, in their case, how to survive and the next meal and laying at your bedroll and getting up with the sun and going to bed with the sun. And you're very attuned to what's going on in the natural world around you. I think for these women even more so because they came into it already attuned to the natural world.

And that changes you in a way that's hard to describe. You come kind of back up to the world above with a different perception of what the world really is. It's addictive and you want to go back right away. I think both of these women felt that, that they wanted to get back on the river as soon as they could. And,

And for Elzada Clover, that never happened. She never ran the Grand Canyon a second time. But Lois Jotter did. She came back when she was 80 years old and ran the Grand Canyon one more time with a scientific trip. So it's hard to put a finger on exactly what that is, but...

You should go on a river trip and experience it for yourself because I think it still happens today. Well, for those of us who won't get that opportunity, certainly we will come as close to it as we could by reading your wonderful, detailed description of it all. So...

Melissa, tell me, what do you think their legacy was, the legacy of these women in terms of our understanding of the botany of the West? I think their work has actually become more important as time goes on because they came back from this trip. They published two papers, including a complete plant list of all of the plants they cataloged before.

before Glen Canyon Dam went up in the 1960s. So this big dam, the second largest dam in the country, goes up right at the head of the Grand Canyon in the 1960s. And it changes everything about the river, about both upstream and downstream, the way the river works.

And so today, when scientists are trying to think about how do we restore this incredibly iconic, incredibly important place to some semblance of its former self, they're looking for historic records to understand what it used to look like. And for botany, this is it.

If Elzada Clover and Lois Dotter hadn't gone on this trip, we wouldn't really have an idea of what the botany of the river used to look like. So I think for science, that is their legacy. As their story becomes more widely known, I'm hoping they leave another legacy as well, which is just the idea that

anyone can do science. Anyone who is passionate about the outdoor world, who's curious about how it all works, can do science. And that's kind of the spark that drew me into wanting to write this book.

Because I think a lot of times when we tell stories about scientists, you get this impression of like the genius in the lab coat, right? We tell stories about Albert Einstein and Marie Curie. But really, science mostly gets done by ordinary people kind of incrementally moving their field forward, right? And we don't tell as many stories about the ordinary work of science, right?

And yet that's really how it works. And it's something that anyone can do. Anyone with a passion and a curiosity can do. And so what really pulled me into wanting to tell this story was that despite being told over and over again that they didn't belong in the field of botany, that they didn't belong running rivers,

These two women ignored all of that and they went anyway. And I'm hoping it will inspire people of all ages and all genders and all backgrounds to understand that if you're curious about something, you can chase it, right? Anybody can do that work.

Wow. That's a wonderful legacy from your book and also for all fans of women in science because we continue to need all the inspiration we can get. And your book is great inspiration. Melissa, thank you so much for this time. And thank you for your book. It's called Brave the Wild River. And it's a great science adventure. Thank you so much. It was lovely talking with you.

This has been Lost Women of Science Conversations. This episode was hosted by me, Carol Sutton-Lewis. Our producer was Laura Eisensee, and Hans Del Schee was our sound engineer. Special thanks to our senior managing producer, Deborah Unger, our program manager, Eowyn Bertner, and our co-executive producers, Katie Hafner and Amy Scharf. Thanks also to Jeff Del Vecchio and our publishing partner, Scientific American.

The episode art was created by Lily Weir and Lizzy Union composes our music. Lexi Attia fact-checked this episode. Lost Women of Science is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Ann Wojcicki Foundation. We're distributed by PRX. If you've enjoyed this conversation, please go to our website, lostwomenofscience.org and subscribe so you'll never miss an episode.

That's lostwomenofscience.org. And please share it and give us a rating wherever you listen to podcasts. Oh, and don't forget to click on the donate button. That helps us bring you even more stories of important female scientists. I'm Carol Sutton Lewis. See you next time. Hi, I'm Katie Hafner, co-executive producer of Lost Women of Science. We need your help.

Tracking down all the information that makes our stories so rich and engaging and original is no easy thing. Imagine being confronted with boxes full of hundreds of letters and handwriting that's hard to read or trying to piece together someone's life with just her name to go on. Your donations make this work possible.

Help us bring you more stories of remarkable women. There's a prominent donate button on our website. All you have to do is click. Please visit lostwomenofscience.org. That's lostwomenofscience.org. From PR.