Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

Hi, it's Phoebe. We're heading back out on tour this fall, bringing our 10th anniversary show to even more cities. Austin, Tucson, Boulder, Portland, Oregon, Detroit, Madison, Northampton, and Atlanta, we're coming your way. Come and hear seven brand new stories told live on stage by me and Criminal co-creator Lauren Spohr. We think it's the best live show we've ever done. Tickets are on sale now at thisiscriminal.com slash live. See you very soon.

Hey, I'm Sean Ely. For more than 70 years, people from all political backgrounds have been using the word Orwellian to mean whatever they want it to mean.

But what did George Orwell actually stand for? Orwell was not just an advocate for free speech, even though he was that. But he was an advocate for truth in speech. He's someone who argues that you should be able to say that two plus two equals four. We'll meet the real George Orwell, a man who was prescient and flawed, this week on The Gray Area.

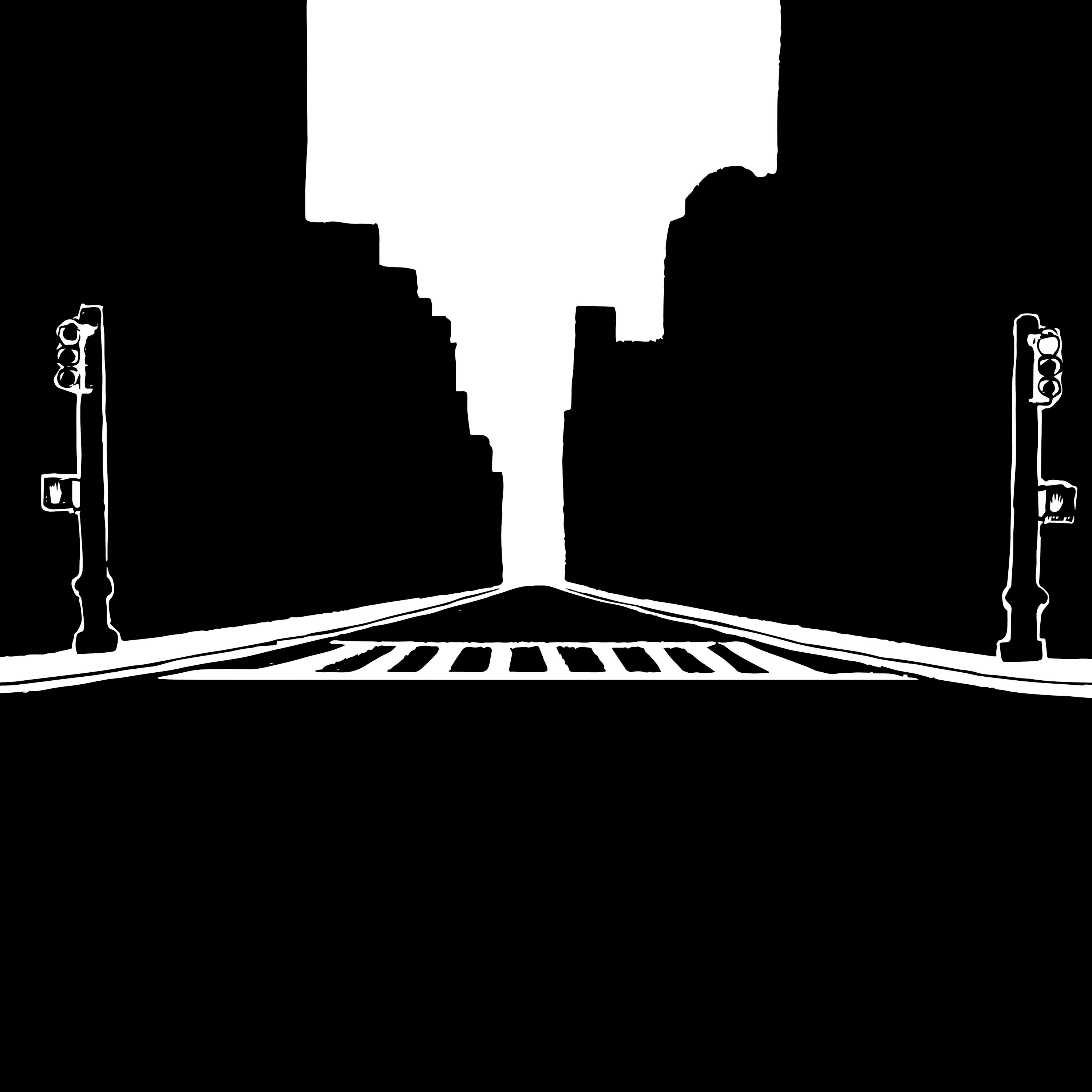

Tupac, at the time, was young. He was brash. And so he's walking with a couple guys on the streets in Oakland here, and he's crossing the street. And two cops stopped him. And he was jaywalking. He was crossing the street. And at an intersection, there was no cars coming. It was 17th and Broadway. This is lawyer John Burris. 17th is a one-way street going through the street.

going in another direction, and he's crossing there at the Broadway intersection. And he's walking. Police officers come up behind him and stop him as he's in the middle of the street and start asking him questions about who was he and his name. And he gave them his name, Tupac Shakur. And they laughed, you know, and said, what kind of mother would name a man Tupac?

And Tupac kind of responded in a negative, you know, snide remark, you know. Well, after they started making fun of his name, he just said, give me my ticket. And then he began to turn and walk away, and that's when they jumped him.

That's when they threw him down, put him in a chokehold, punched him up some, and then abused him in ways that was just unjustified. And then they arrested him, took him to jail for resisting arrest. This was October 17th, 1991. Tupac Shakur was 20 years old. He said he lost consciousness during the arrest and that he was held for seven hours in jail. They were charging me with jaywalking.

So I was riffing, arguing about why would they charge me with such a petty crime. Next thing I know, my face was being buried into the concrete and I was laying face down in the gutter, waking up from being unconscious and cuffs.

with blood on my face, and I'm going to jail for resisting arrest. That's harassment to me, that I have to be stopped in the middle of the street and checked, like we're in South Africa, and asked for my ID. Officer Boyovic repeatedly slammed my face into the floor while Rogers put the cuffs on me. That's not called for, for jaywalking. John Burris represented Tupac Shakur in a lawsuit against the city of Oakland. They sued the city for $10 million.

Eventually, the city settled out of court and reportedly paid Tupac $42,000. It was symbolic and representative of the type of brutality and the type of misconduct that was taking place among OPD officers, Oakland police officers, toward black citizens, and Tupac was one. John Burris later told a newspaper columnist that he was getting four or five new police brutality cases every day.

Many of them originating from jaywalking and traffic stops. Do you think jaywalking should be a crime? Hell no. Jaywalking should not be a crime. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal.

Jaywalking, unless you have really caused an accident or you're disrupting the traffic flow in some way, there really shouldn't be any basis for stopping you and arresting you. And when I've had these cases, I have been particularly offended that you would come out of nowhere, a cop would come out of nowhere, see you had jaywalked a block away or so, and then stop you for that jaywalking when cars had not been stopped.

and people had not been injured, that should not have been a basis to stop someone and to give them a ticket and to cause them to go into the criminal justice system. Because I know from my experience as a lawyer, there's real harm to a person. An ordinary person gets caught into the criminal justice system, there's collateral damage.

You wind up having to get a lawyer. You may have to pay that lawyer. You may plead guilty because you don't have a lawyer. You get on probation. Then, you know, then when you get into criminal justice system, then you could, that could affect the kind of job you can get. It could affect your student loans. It could affect any number of things, particularly if you're found guilty of it. But jaywalking was not always a crime. The Ford Model T came out in 1908. It was the first car that was affordable to most Americans.

It cost $850, but quickly became even cheaper. People called it the Tin Lizzy. Other cars were selling for $2,000 to $3,000. The Model T became so popular that Henry Ford said, there's no use trying to pass a Ford because there's always another one just ahead. There are a lot of new cars on the road, a lot of new drivers, not a lot of rules, and very few traffic lights at all.

And it was much more of a free-for-all, which might sound a little chaotic, but actually, as people know from navigating busy corridors in a hospital or an airport, people are actually typically pretty smart about how they move around when you let them make up their own minds about what to do.

Peter Norton is an associate professor of history at the University of Virginia. But automobiles were going faster, and there was no driver's ed then, and the mix was dangerous. In the spring of 1920, a nine-year-old in Philadelphia named Leon Mortel was playing on the sidewalk with his friends. A car jumped the curb and hit Leon, who died. Two years later, Leon's brother, Howard, was also hit by a car and killed.

He was 18. Leon and Howard's father, Barnett Wartell, wrote a letter to Herbert Hoover. At the time, he was the Secretary of Commerce. Barnett Wartell wrote to Herbert Hoover to say, we need to do something about this. And the actual way in which he writes this letter, I think, is incredibly significant. Because there's no question in Barnett Wartell's mind that his sons were innocent victims of

a dangerous new abuse of the streets. He calls the people who strike and kill pedestrians, he calls them murderers. In the 1920s, Karras killed over 200,000 people in the United States.

In 1925 alone, 7,000 children died. And so to me, that letter stood for a view of the street as a place for everyone, not just motorists, even children, and a place where if you wanted to operate a dangerous machine like a car, the responsibility was on you to operate it in a way that would not endanger other people. In 1923, a Philadelphia woman was hit by a car while waiting for a trolley,

and the driver tried to get away. Bystanders chased and caught him, and then more and more people gathered, surrounding him to make sure he couldn't escape. Newspapers reported that it was 2,000 people. Phrases like death drivers and vampire drivers appeared in newspaper headlines. Cartoonists drew drivers as the Grim Reaper. In one cartoon, a man is shown offering a plate of sacrifices to a car.

Cities built memorials to the victims of car accidents. Baltimore built a 25-foot obelisk for children killed in accidents in the city in 1921, especially the victims of traffic accidents. There were memorial parades all over the country. In New York, 10,000 children marched up Fifth Avenue. 1,054 of those children were meant to represent children who had died in accidents that year, many of them in car accidents.

They were led by Boy Scouts carrying a papier-mâché tombstone. As car accident deaths continued to rise higher and higher, one automobile executive named George Graham told his colleagues, "Pedestrians must be educated to know that automobiles have rights." We'll be right back.

The Walt Disney Company is a sprawling business. It's got movie studios, theme parks, cable networks, a streaming service. It's a lot. So it can be hard to find just the right person to lead it all. When you have a leader with the singularly creative mind and leadership that Walt Disney had, it like goes away and disappears. I mean, you can expect what will happen. The problem is Disney CEOs have trouble letting go.

After 15 years, Bob Iger finally handed off the reins in 2020. His retirement did not last long. He now has a big black mark on his legacy because after pushing back his retirement over and over again, when he finally did choose a successor, it didn't go well for anybody involved.

And of course, now there's a sort of a bake-off going on. Everybody watching, who could it be? I don't think there's anyone where it's like the obvious no-brainer. That's not the case. I'm Joe Adalian. Vulture and the Vox Media Podcast Network present Land of the Giants, The Disney Dilemma. Follow wherever you listen to hear new episodes every Wednesday.

In 1924, automobile executive George Graham established a news service run by the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce. It was free. Newspapers sent in accident reports, and George Graham's service would send back monthly statistics and safety suggestions. This meant that the carmakers were telling the press what happened and who was and who was not responsible.

Soon, a magistrate in New York City's traffic court wrote that he had noticed that newspapers now said 70 to 90 percent of all accidents were the fault of pedestrians. And it's astonishing how effective this was. You can see these news articles appearing and the headlines changing. All of a sudden, all of the newspapers were blaming pedestrians. The car industry also started printing posters,

One shows a line of kids standing in front of a chalkboard, signing their names under the words, "I resolve to cross streets carefully." Around this time, a new word was becoming popular: jaywalking. Back in 1920, the word "jay" was used to signify ignorant, especially rural. You were, a jay was a hick, a rube, uneducated, old-fashioned, out of date.

And it was also a useful word because it was treated as a prefix for almost anything you wanted. So a J-town was a town with no library, and you could use J as a prefix for other terms, including Walker. So J. Walker meant you're an ignorant person who's out of date and doesn't know what people in the Motor Age do when it's time to cross the street. It was a term with so much sting that the New York Times ran an editorial saying,

saying that officials should never use this word because it's a term of such offensive abuse that has no place in courtrooms or on law books. So it was a term with a lot of sting, and that sting was intended to deter people from walking the way they always had. Safety parades started to include the jaywalker. In one, actors were hired to play pedestrians, causing accidents.

In another, there was a clown who was hit by a Model T over and over. Packard Motor Car Company built a float in the shape of a tombstone with the words, "Erected to the memory of Mr. Jay Walker, he stepped from the curb without looking." The Detroit Automobile Club gave the company a trophy for having the best float in the parade. The Washington Post described the Jay Walker as, "A man who will take the last piece of bread on the table,

The man whose wife fixes the furnace and buys his clothes. Show me this man, and I will show you a jaywalker. One newspaper in San Francisco asked people if jaywalkers should be jailed. Cities around the country tried to pass laws to make it illegal for people to walk in the street. It often backfired. I know of at least one case where

Women in Kansas City used their parasols against police, striking them with them as a way of saying, you know, you have no right to limit my use of my own streets. So arresting people for jaywalking was a tough proposition. The resentment was such that you quickly found the population engaged in a kind of civil disobedience campaign where they simply would not go along with this.

Los Angeles adopted a jaywalking law in 1925. Pedestrians were required to stay on the sidewalks and only cross the street at crosswalks and only at right angles. It was championed by a man named E.B. Lefferts, the president of the Automobile Club of Southern California. The first week after the law went into effect, police made just a handful of arrests.

In that time, one woman slapped an officer and another man planted his fist on the jaw of the patrolman who tagged him. E.P. Lefferts asked the police to hold off on making arrests. He had an idea. There was a massive public relations campaign. It was even on the early radio. This is the very early years of radio. It was in the newspapers explaining to people...

That it's a new age, it's the 20th century, it's the 1920s, it's the automobile era, the motor age. The modern way to cross the street is to wait at the intersection, not to get in the way of motor vehicles. That's too dangerous. So if you're a jaywalker, basically you're kind of old-fashioned. You're in the past. You don't get it. Cars are here. This is going to make our country better, our cities better. It's a sign of the times, and you're...

You're old-fashioned. Exactly. So, I mean, a person who in 2023, you know, gets out their flip phone is going to attract some funny looks, right? And Jay Walker was intended to...

apply that same kind of social pressure, but in a deliberate way, where people feel awkward. The other part of E.B. Leffert's strategy was to tell police officers to draw as much attention to the jaywalkers as they could. He even advised police to deter pedestrians from crossing in ways that would look embarrassing or bring ridicule to them.

Police officers would blow their whistles at jaywalkers, quote, pointing the finger of scorn. One pedestrian said of the whistle that, At one point, officers went out in plain clothes to surprise jaywalkers. The L.A. Times called it guerrilla warfare.

The most astonishing of these recommendations was that if a woman was jaywalking, a police officer should pick her up by the arms and walk her back to the curb. And the intention was to humiliate her in front of crowds of people. And with the intended effect that the crowds would see this and perhaps laugh and derision, but even more importantly, recognize that they would never want to be in that situation themselves. It worked.

To this day, that Los Angeles traffic ordinance is the number one source of influence. It's like the ancestor, the first ancestor of practically all of the pedestrian restrictions that are on the books today. They were modeled directly on that Los Angeles ordinance. Jaywalking laws appeared more and more across the country, and arrests became more and more common too. Certainly, though, it took some time. They were typically always controversial incidents.

There was a really extraordinary case in Washington, D.C., where there was a real rift within the police department over whether to arrest people or not. One police chief favored it, went on vacation, and another police chief stepped in and sort of absolved all of these pedestrians of their legal responsibility because he thought streets are for everybody.

But, yeah, over the course of the next decade or two, it became routine. Like a parking ticket, you could get a ticket for walking where you wanted. And, yeah, we've inherited that. So it basically changed it from if you want to cross the street, you will do it in these certain areas. And if you don't do it in these certain areas and you get hit—

It's your fault. Exactly. Now, so one of the most stressful parts of being a driver in the early 1920s was that you were at constant risk of enormous liability for injuring somebody because the pedestrian had an absolute right to the street everywhere. And this was really what the jaywalking laws were intended to change. So yes, exactly right. If you hit somebody after these laws were introduced...

and that person was not in a crosswalk, you were likely to be held not liable for their injury or their death, especially if you were driving in a legal way, not speeding too much. A few months after the law went into effect, the LA Times reported that it had sped up traffic 25%. Peter Norton says that in the 1920s, traffic engineers began to organize city streets.

It became customary for cars to drive on the right side. They designated some streets as one-way only, and they instituted parking bans during rush hour. A public official in Cincinnati said, as traffic demands grow more acute, the use of streets for other purposes must be more and more restricted. In 1925, Ford Motor Company said it was making the most cars it ever had.

The Los Angeles Times reported in Southern California, every third person now owned a car. Today, over 90% of households in America have at least one car. Over 20% have three or more. It's funny, now you have these cities that are saying we're going to take the streets back, and so there's these new campaigns which block off the streets to pedestrians, you know, on Saturdays from 10 to 4 p.m.

It's gone full circle. Yes, that's right. And movements and trends we've been seeing, especially over the last 20 years, I think expose a historical lie that most of us grew up with. I know I did. The historical lie that I recall learning in museums, in history books, and in classrooms was that the status quo, namely sort of car priority everywhere, driving everywhere, people...

deferring to drivers if they're walking or if they're riding a bike, that that status quo was the democratic choice, the popular preference, or the consumer demand in the marketplace. Frame it how you like. And I think what we've really found instead is the fact that Americans did not ever choose car dependency.

That world was never the product of mass preference. And the industry groups that pushed for that world are the best proof that it wasn't the democratic choice. Their own conversations, which I've read in detail, their internal conversations, are full of statements like, well, how do we possibly overcome this mass preference for riding the streetcar and for walking?

I recall reading one conversation between industry insiders in the 1930s where they're wringing their hands over the fact that lots of people in big cities like Chicago and Boston who could easily afford a car were not buying one.

And so they sat around and thought about how do we convince people that they need a car? One of the answers they came up with was, well, if we build expressways through all of our big cities, then, you know, people will need a car to get around. And it was not subtle.

A few years ago, he noticed that there was one place in his neighborhood that seemed pretty dangerous.

The four-lane Glendale-Hyperion Bridge that went over the Los Angeles River. Anybody who doesn't have a car and needs to get from one neighborhood to the next has to try to get onto this bridge. And there's no crosswalk, there's no signalized light, and cars can be going up to 60 miles an hour. In 2015, the city decided to install new bike lanes on the bridge. But to do it, they said they needed to remove one of the sidewalks.

If they did that, people could only walk on one side of the bridge, and there would be no way to cross safely. It means that kids who lived on the south side of Atwater Village were going to have to walk almost a quarter of a mile into town, into Atwater, cross three traffic lights,

We'll be right back.

One night, Sean Meredith and a friend went out to the Glendale-Hyperion Bridge. They brought cans of spray paint. They waited for cars to pass. And when there was a break in the traffic, Sean went into the street.

I would just walk across the street doing a line. And then we added more lines, and then there were the cross lines. And we just went over and over again. I would be concentrating on the painting, and my friend would be concentrating on yelling out, if, you know, abort, you know, the car is coming really fast this time, so you don't have time to finish that line. So we just did it and did it and did it. And then after that, we actually also took...

an old wooden statue, a carved statue of a young man. And we put like a reflector vest on him and put a flag kind of stuck in his arm. And we chained him to the bridge right where the crosswalk was, kind of like a crossing guard, just to help with visibility because people are coming so fast.

And then, Sean says a California Highway Patrol car pulled up next to them. Highway Patrol comes up and, you know, starts asking us questions. And so we thought we were going to get busted for the crosswalk. But what they wanted to question us about is why did we have this statue on the bridge? And we said it was for an art project, I think. I think they thought we were shooting a film about...

Because, you know, it's L.A. They don't want you doing filming without a permit. Did they notice the crosswalk? I don't think so. I don't think so. They were parked over it. Like, they pulled right up to us and stopped right on the crosswalk. Sean says the next day he went to check on the crosswalk. He took some pictures. But then a few days later, it was gone. Someone from the city had painted over it.

I always found it really striking because when they did it, it's almost like they created like a negative crosswalk. The black paint was so much blacker than the street, it created almost kind of like an uncrosswalk. In 2022, a group called the Crosswalk Collective started anonymously painting crosswalks in Los Angeles. You can put in a request, just like you would ask the city to install a crosswalk. The collective put out a guide for how people can paint their own,

Members have sometimes been stopped by police. Once, several members were fined $250 for injury to public property. What do you think about the fact that jaywalking first became criminalized in L.A. by car lobbyists? Well, much of what happens in life...

in terms of new laws that's political in nature. John Burris, the attorney who represented Tupac in 1991. I don't think that that's inappropriate to be concerned about the safety of people walking across the street. I just don't think that we should have laws that interfere so aggressively around jaywalking when, you know, people can take care of themselves.

It doesn't make sense to me that you have people being charged with crime for jaywalking in some cities and not in others. John has been practicing law in California for over 30 years. For much of that time, jaywalking was considered a misdemeanor. In 2017, John Burris took a case in Sacramento. A man named Nandy Cain Jr. was on his way home from work.

He was walking. Crossed one, two streets. No cars coming. There were no crosswalks either. So about a block and a half down after crossing the streets, a police officer comes up behind him on a motorbike and jumps off and tells him to stop. Nanny King first didn't stop. Then he kind of looked around and said, what did I do?

And the police officer told him to get on the ground, and Nandy was kind of reluctant to do so, but he was trying to get down. The officer then comes up behind him, grabs him, throws him down, and literally beats him, punches him, punches him, and punches him while he's on the ground. And Nandy is like, what have I done? What do I do? Nandy Cain ended up with a broken nose and concussion.

Just like Tupac, he was charged with resisting arrest. He was beaten up pretty badly, and so I represented him in connection with that case. And ultimately in that case, we were able to resolve that case in a settlement, but we also got the department to have to accumulate some data

The city of Sacramento agreed to track how often people were stopped for jaywalking, and who was stopped for jaywalking, and make the information public for three years. And what we saw, and we always saw, at least in terms of my history, was African Americans who were being stopped by white police officers. So, you know, there was always this implicit racial bias that existed within these types of offenses. Now look, racial bias and racial profiling in policing is a common phenomenon.

African Americans have subject to traffic stops, bogus traffic stops, or stops for very minor, minor offenses, historically. A year after Nandy Cain's assault in Millbrae, California, just south of San Francisco, police stopped 36-year-old Chinadu Okobi for jaywalking. The officers used a taser on him. Chinadu lost consciousness and died from cardiac arrest.

Two years later in San Clemente, police stopped 42-year-old Kurt Reinhold on suspicion of jaywalking. In footage from the police car's dash cam, one officer says, watch this, he's going to jaywalk. The officers approach Kurt Reinhold, and then they tackled him. In the struggle, one of the police officers shot Kurt. He was killed.

In 2021, Phil Ting, an assembly member in San Francisco, cited all three cases as reasons to decriminalize jaywalking in California. He proposed a bill called the Freedom to Walk Act, making it so you can't be stopped for jaywalking, as long as you're crossing the street safely. The bill passed and took effect in 2023. ♪

I think the law itself, although it's relatively new, should decrease the encounters. But as we know, you know, and you probably know as well, because they're arbitrary in the sense that any police officer can decide arbitrarily whether that offense itself is worthy of being stopped. California is just one of three states in the country that have changed their jaywalking laws.

Criminal is created by Lauren Spohr and me. Nadia Wilson is our senior producer. Katie Bishop is our supervising producer. Our producers are Susanna Robertson, Jackie Sajico, Lily Clark, Lena Sillison, and Megan Kinane. Our show is mixed and engineered by Veronica Simonetti. Julian Alexander makes original illustrations for each episode of Criminal. You can see them at thisiscriminal.com. And you can sign up for our newsletter at thisiscriminal.com slash newsletter.

We hope you'll join our new membership program, Criminal Plus. Once you sign up, you can listen to criminal episodes without any ads, and you'll get bonus episodes with me and criminal co-creator Lauren Spohr, too. To learn more, go to thisiscriminal.com slash plus. We're on Facebook and Twitter at Criminal Show and Instagram at criminal underscore podcast. We're also on YouTube at youtube.com slash criminal podcast.

Criminal is part of the Vox Media Podcast Network. Discover more great shows at podcast.voxmedia.com. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal. ♪