Check 6 Revisits: A Grand Canyon Crash And Its Impact On Aviation Safety

Aviation Week's Check 6 Podcast

Deep Dive

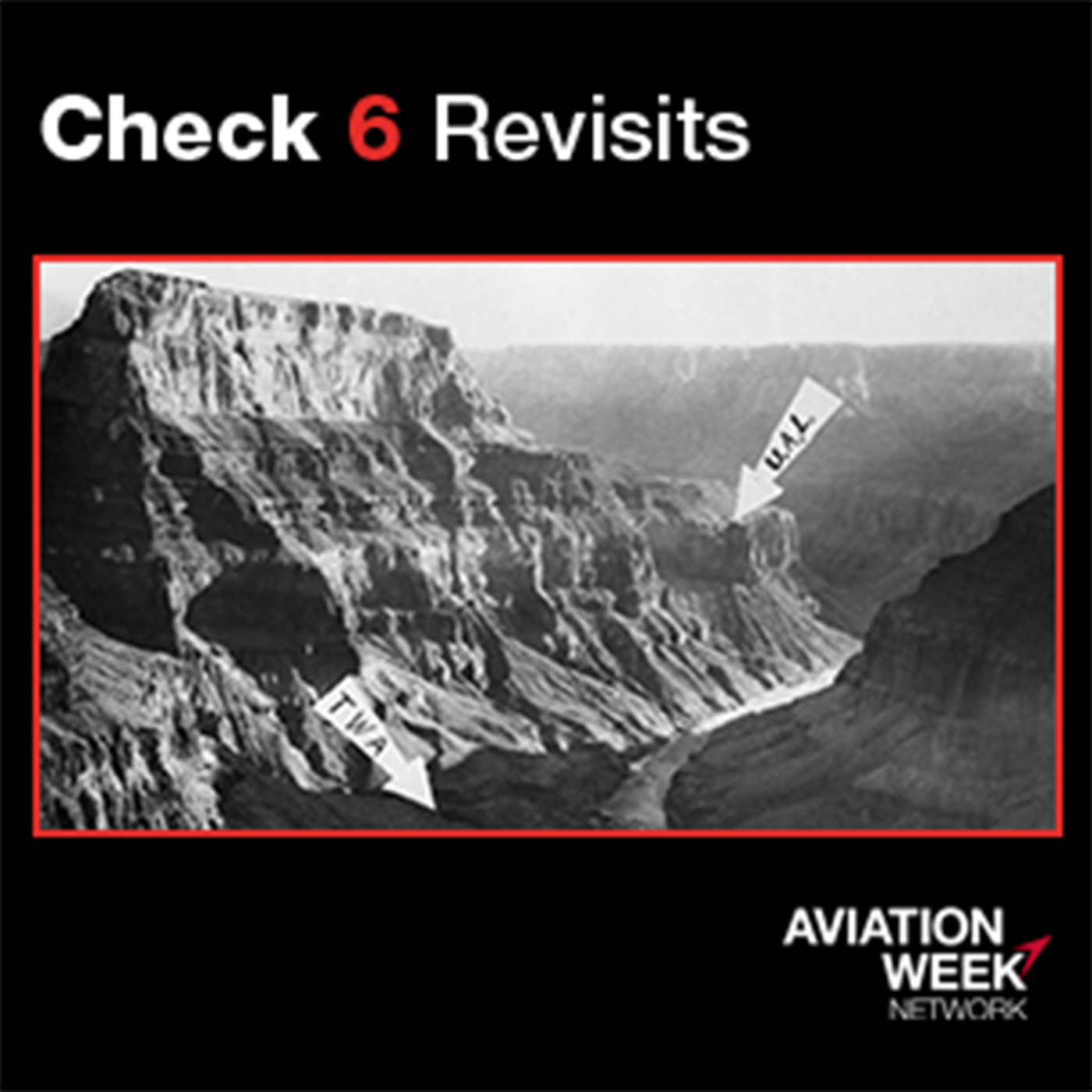

- Mid-air collision between United Airlines DC-7 and TWA Super Constellation over the Grand Canyon.

- 128 fatalities.

- Collision occurred at 21,000 feet despite planned altitude difference.

- Probable cause: pilots' failure to see each other due to weather conditions, workload, and inadequate air traffic control.

Shownotes Transcript

College students qualify for free digital subscriptions to Aviation Week and Space Technology. That includes access to our archive, a valuable resource that contains every issue back to 1916. To sign up, go to aviationweek.com slash student.

Welcome to Check Six Revisits, where we comb through more than a century of Aviation Week and space technology archives. On this podcast, our editors explore pivotal industry moments and achievements of the past, while considering how they might relate to the events of today. I'm your host, Christine Boynton, Aviation Week Senior Editor for Air Transport, and today we'll start at the Grand Canyon in June 1956. This first interview is the

First interview made with Cecil Richardson, the Coconino County Sheriff, with his first statement to the press that the TWA plane had been sighted. This interview was made direct from the Sheriff's office on Saturday night, July 30th, 1956.

This is Jack Murphy reporting from the Coconino County Sheriff's Office and flight staff on the passenger plane tracks that occurred in northern Arizona this morning. Reports have been coming into the Sheriff's Office constantly and have been checked out thoroughly by Coconino County Sheriff Cecil Richardson, who we have here on our phone line now. Sheriff, could you indicate what the latest reports are and the location of those reports? The record is at least one of the airliners is in the area.

has been found on the south slope of what's called Tar Pook. That's our latest information and that is just a little west and south of the Little Colorado River and the Colorado River. And it will be hard to get to it. You'll have to go in by, probably with helicopters in the morning. Sheriff, how close do you think that you're, first, will you send a ground party in there tonight or will you wait until daylight?

We'll have to wait until daylight because it's too rough to send someone in with the helicopters in the morning. And then they start...

The rest of the tip that is down in there on their report. This crash area has been pointed out as actually being inside the Grand Canyon National Park. Is that correct, Sheriff? As far as we know, it is inside the Grand Canyon National Park.

What you've just heard is an interview with the Coconino County Sheriff following a mid-air collision between a United Airlines DC-7 and a TWA Super Constellation. All 128 aboard both aircraft were killed. It is perhaps the most well-known in a series of mid-air collisions around that time that would spur much-needed change.

The prior fall, a series of Aviation Week editorials had warned that mid-air collisions could be the consequence of what it dubbed, quote, a lethal combination. That is, an antiquated air traffic control system and the increases in both speed and density of modern air traffic.

For a little perspective, between the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938 and 1955, the number of airline passengers went from about 1.5 million to more than 41 million. Post-war years gave us airports, airfields, and pilots, causing air traffic to spike. Then the jet age added a much more technically capable airplane to the fleet. This was all within about a decade and laid on top of an aging ATC system.

Following another mid-air crash in April 1958, the fifth such in three years, then Aviation Week editor-in-chief Bob Hotz took stock of what actions had been taken towards much-needed modernization and what had hindered progress.

Potts wrote, quote,

He pointed to, quote, years of executive indifference and congressional reluctance to appropriate money as having stalled vital actions. In late 1958, with a series of collisions spurring action, a new independent FAA was formed and tasked with civil aviation safety. So there's a lot to unpack here. And joining me today to do so are Aviation Week senior editors Bill Carey and Sean Broderick.

Also joining us today is Randy Babbitt, who brings a really unique perspective to today's chat, four hats really, as a former pilot, union leader, FAA administrator, and U.S. airline executive. So welcome, Randy, and thanks for joining us today. Well, thank you. Thank you for having me. So I kicked us off with a very high-level overview, but Bill, can you maybe get into the Grand Canyon crash with a little bit more depth? How did that happen? Sure.

Sure. And it's great to be here with former FAA Administrator Randy Babbitt and my friend and colleague, Sean Brodrick. So, Christine, you opened with the 1956 mid-air collision over the Grand Canyon. This was in the post-World War II era during the Eisenhower administration when air traffic control was primarily conducted by radar and radio communications with pilots.

But as HOTS warned about, there was a growth in both the density of air traffic and the speed at which aircraft operated, including the coming introduction of jets into the civil aviation fleet. But anyway, this collision resulted in the deaths of 128 people on board both airliners. Both had taken off from Los Angeles International Airport that morning, only three minutes apart.

The TWA flight was to Kansas City. That departed first and initially routed north, while the United flight to Chicago initially routed south. Their flight paths were planned to cross near the Grand Canyon, and as the Kansas City flight routed back south and Chicago flight routed back north. Although the flight plans called for the flight paths to cross, the planned altitudes differed by 2,000 feet.

However, the flights both ended up at an altitude of 21,000 feet when they collided over the Grand Canyon. This is according to an FAA history. The FAA has a great historical page on their website, which I would recommend. The probable cause finding of that accident by the Civil Aeronautics Board in April of 1957 is,

The CAB was a predecessor of today's NTSB, and it was an independent agency within the Commerce Department.

was that the pilots, this is a quote, did not see each other in time to avoid the collision. And then it goes on to say there were intervening clouds reducing the time for visual separation, visual limitations due to cockpit visibility, preoccupation with normal cockpit duties, preoccupation with matters unrelated to cockpit duties, such as attempting to give passengers a more scenic view of the Grand Canyon,

physiological limits to human vision. And I think last but not least, which is cogent to our discussion today is the insufficiency of en route air traffic advisory information due to inadequacy of facilities and lack of personnel and air traffic control. That was kind of the summary of the probable cause finding the Civil Aeronautics Board in April, 1957.

And Sean, what else was going on around this time? Sure. So part of, I think part of the, the real core of that accident was the lack of a

air traffic control of the two airplanes. And at least one of, I think it was the TWA flight, was flying what was called an IFR on top clearance. And I think Randy can probably help us a lot more with this. He's probably flown one or two in his life. But basically it was, so they were not under radar control. And if you fly an IFR on top clearance, that meant you were flying,

IFR procedures, but you could do it in VFR conditions, which means you did not necessarily have to stick to the altitude

that you were assigned. And I believe they were flying an AFR 1000 on top, which basically meant their altitude was going to vary by, you know, a thousand feet plus or minus. And again, Randy can correct me on that one. And the part that Bill talked about through the Grand Canyon, getting the view of the Grand Canyon, apparently a very common thing back then. And so you put those two things together and what you have is basically two airplanes flying roughly along the same route. They were...

you know, going over the same unofficial waypoint, which is the canyon. They didn't see each other.

And because there was no mechanism in place besides the pilot's ability to look out the window and avoid each other, and that's sort of what happened. Randy, you wanted to throw something in, but please correct me if I'm wrong on either of those points on top clearances. No, that's accurate. I don't think – I haven't heard that phrase in a long time, so –

It was. There's a reason for that. So at the time, so at the time, the most the thing that struck me when doing, you know, when when going through the old issues of the magazine and some of these reports to prepare for this for this podcast was.

And both of you have already touched on this, Christina, about the pace of change that was going on at the time in the industry. And just for perspective's sake, if you take 1956 is where we started. If you go back two decades to the late 30s, so 1936, there wasn't even an independent agency yet.

to overseeing air safety or air route development or anything. It wasn't until 1938 that Civil Aeronautics Authority was created. So aviation was under the Commerce Department. If you do that today, 20 years ago, we were at the beginning of NextGen.

So, if you think about, we've been talking about the same modernization program for two decades. You go back 20 years from that Grand Canyon collision, there wasn't even an agency to manage a modernization program. But it changed very quickly. It doesn't mean that there weren't efforts, or at least calls, beyond the pages of Aviation Week and Space Technology Editorial to make these changes.

But there were some interruptions there. So 1938, the Civil Aeronautics Act came around. And that didn't even last long. President Roosevelt in 1940 split the CAA into two agencies. A lot of people forget this. Civil Aeronautics Authority was ATC and Airways Development. And then CAB, Civil Aeronautics Board, which we sort of think as the precursor to the FAA, even though they really both were.

was safety and economic regulation. Then you hit World War II, and as Bill talked about, and you did too, Christine, the pace of development on aircraft technology and pilot training and some of the things that would become important in air traffic control really took off, but none of that was applied to civil aviation flying until after the war.

So you get to 1946 and you have airlines that want to sort of continue. And the airlines did very well during the war because they worked, you know, for the for the Department of Defense or, you know, they worked in support of the war effort. They get back out there. They're beginning to have pilots. They have people that want to travel. They have new airfields, new airplanes in development.

And they had a military that was used to controlling the airspace because if you remember how we got into World War II, it was arguably partially an air defense failure, right? So very quickly, it became clear that all

the stakeholders at the time, and that was, you know, for better or for worse, the Departments of Commerce, Department of the Navy, the Post Office, the War Department and the State Department and the Civil Aeronautics Board, they were all told to get together on something called the Air Coordinating Committee.

And the Air Coordinating Committee very quickly determined that they needed some expertise to figure out how to handle the emerging air traffic control technology or modernization challenge. So they handed or they requested or that task ended up in the hands of a group called the Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics.

which still exists today. We know it as RTCA. They were tasked with studying air traffic expansion and how to best manage it. Special Committee 31, RTCA, recommended a specific air traffic control system using technologies, VH, VOR, and DME is the primary navigation system, which again was new back then.

And they also looked at how computers were developing sort of in parallel with the aviation industry and said computers are going to be very important for managing terminal area traffic. And this would become, over the preceding 12 years, the terminal area issue would become huge, but would be one that wasn't dealt with as quickly as

as en route and even air traffic control towers. So Bill talked about what happened in the 50s. The first airport to use radars for departure and arrivals early 50s was National and LaGuardia. At LaGuardia, departure control or arrival controls by controllers tripled arrival rates to 15 aircraft per hour.

That was tripled with the technology. So you think about, again, where we were, that led to one of the editorials that Bill referenced where our esteemed editor called the air traffic control system a DC era system, DC free era system, sorry, air traffic control system that was insufficient and really a safety hazard. So when that accident happened, there was another key

study that was going on that really was the catalyst for forming what we have today. President Eisenhower at this time picked a retired World War I flying ace and Army Air Corps Major General named Ted Curtis to become what was called the Special Assistant to the President of Aviation Facilities Planning. And his job, well, he had given a couple of tasks, but the most important one for our conversation was

was to determine the direction and coordination of a long-range study of the nation's requirements for aviation facilities. So Curtis was in the middle of this study when the Grand Canyon accident happened. So in April 1957, he fast-tracked what he was doing. So, you know, circle the calendar to April, because that's the pace, I guess, of some of that stuff back then. He submitted an interim report saying,

And it had a couple of key recommendations. And one of them was to develop a new bureau to manage air traffic, air navigation facilities, to develop them. And within four months, that became law.

A year later, we had the Federal Aviation Act 1958, which created the FAA. And that really got us going to where we are today. It's amazing. If you look at the Curtis report, though, even some of the other, he knew how fast things were going. But if you look at some of the numbers that he had, he expected by 1975, there would be 70 billion revenue passenger miles, up from 20 billion in 1956. The actual figure in 75 is 163 billion.

Private aircraft, there were 61,000 when he wrote his report. He figured there'd be over 100,000 by 75. There actually were over 200,000. So they understood the rate of growth then, but it was going to get even worse, or even more not worse, more acute. So it was in the middle of all that that this accident happened, and there were 3%.

three, I think three other major midair collisions, including one over New York in 1960.

that were really the catalyst for changing not only some of these things that were lacking, but also adding terminal area control. And the one in 1960 put in things that you would think we take for granted now, but weren't in place back then. Things like speed restrictions in the terminal area around airports. We think about how quickly the jet, the DC-6, DC-7, and then DC-8, how quickly the jet age came, 707-2.

You didn't have to think about those speeds when you were developing air traffic control procedures in the 1940s and even early 50s. But by 1960, you tell somebody to approach a fix or slow down, and you're going to have airplanes flying at very, very different speeds against something probably Randy can speak to.

So that's the environment we were in, and some parts of it were moving incredibly fast, and other parts were moving glacially until this series of accidents happened that that 1956 midair was right in the middle of. Mm-hmm.

Well, thanks, Sean. Randy, you've had the opportunity to experience air traffic control, as I mentioned, sort of with wearing four hats, right, over the years. And you started as a pilot with Eastern Airlines. And I'm wondering if you can kind of give us your perspective on air traffic control challenges and air traffic control just in general as you've moved throughout your career in those different positions, maybe starting as a pilot. Sure.

Sure. Well, I think Sean did a great job of, you know, sort of setting the benchmark and taking this forward. I started flying for Eastern Airlines about 10 years after that accident.

We had radar. You had flight plans. You still were doing some of the basics that visual airplanes would fly at odd altitudes plus 500 feet going in one direction and even altitudes and 500 in another. And ironically, people find this hard to believe, but in the 60s,

your obligation to file a flight plan was limited on the weather. If the weather was bad, you had to file an instrument flight plan. If the weather was nice, you didn't have to. You could fly visually and you could cancel.

And people now, of course, jets are required. But, you know, over time, these things changed. And, you know, you look back, you could just cancel your flight plan. Yeah, if the weather was good, you would just cancel and just go direct and save time, save fuel. And obviously, as time has gone on,

Accidents, unfortunately, it's like the stoplight at the school. You have to have an incident with children or something. Then you put up the stop sign. Then you put up the crossing guard. Then you do, well, I had a terrible crash in San Diego.

And that changed your ability to just cancel and go a visual. And everyone, you will maintain your IFR separation. You'll stay under those rules. Then we changed the speeds. You get down below. That change came about probably, I'm going to say Sean probably knows better than I do, but I'm going to say somewhere around 1970, 2000.

below 10,000 feet, you had to fly below 250 knots. 250 knots or slower. Up until that point, you could come into the Atlanta area going 350 knots and, I mean, at 2,000 feet, it was crazy.

And so, you know, each one of those takes, you know, a piece, a piece, a piece, making it better, better separation. The problem that we've seen, I think twofold, is every generation of airplanes gets more sophisticated. They're faster. They do other things faster.

But we don't have the air traffic control system modernizing at the same rate. It is not a system that's adaptable to evolution. In other words, we'll just change a few things and it'll just keep getting better every year. No, you pour concrete and this is a system you're going to have for the next five years, period. And if you want to change it, then we'll do something and it'll take two or three years. And, you know, people think it's a modern system.

Christine, I might have told you, one of my early chuckles was taking Secretary Pena on a tour of one of the radar facilities up in O'Hara. And he was just fascinated. The big green scopes and airplanes. And he just thought this was fascinating. And he said, wow, this is just so modern. This is just incredible.

And I looked up and I said, with all due respect, Mr. Secretary, when was the last time you saw the word UNIVAC written on something? And that's how old it was. I mean, this is ancient stuff. And we still have facilities that I think there's a few left, depending on some systems that require vacuum tubes. I mean, it

So, you know, we've got to, A, decide, you know, what is a better system and how we're going to do it. But it has to be built so that it can evolve. It's technology. You know, the leaps and bounds, you know, will AI come into air traffic control? I'm sure it will. I mean, it's got to be tested. A lot of things will happen, but it will get there and it will get better. But we need to have systems that evolve and then evolve.

the other side and having worn a couple of the hats you mentioned, people would say, well, the FAA should have done this. It's, you know, well, who's the decision maker here? The FAA says we want to do this. And the Department of Transportation says, no, no.

No, politically, we can't do that. It's too much money. And, oh, really? So you can't decide? No, because, well, actually, Congress decides. They decide how much money. So at the end of the day, the group that gets blamed for everything is a group that may have been screaming for years, we need more money to fix the system, and you have to appropriate it, and it has to go through channels, and it takes time.

Hopefully. I mean, we've made such tremendous improvements in air safety. I mean, I remember one of the folks, I think the other one had a statistic that I really enjoyed that, you know, we used to measure accident rates, hull losses by 100,000 hours. And if we had the hull loss rate today that we had in 1970, we would lose an airplane every three weeks.

Wow. That's how much we've improved. And we went 13 years without one accident. So it's a pretty remarkable change. So can it get better? Yes. And does it need to get better? Absolutely. And we have the technology. We just need to embrace it, fund it, and move on. And

You know, we can't get behind like we did here. I appreciate COVID and, you know, laying people off and everything. But when you lay somebody off, they're gone in a week. If you say, I want them back, it's two years. It's two years, a controller, from the day you hire them. And that's not a fully, that's not somebody, when I had to bet somebody trained

Maybe they could be the tower operator at Ocalaca Airport or something, but they're not going to a fair approach control for Atlanta, not with two years. And so it takes a long time for these skills to build up. Unfortunately, I think we're moving in the right direction. I think we've got some new avenues to train controllers more quickly, better.

in the mill, but still, it does require careful attention to staying up to date and staying modernized and staying ahead of the curve. And Randy, I think you did a lot to advocate for next gen and to try to move that effort forward. And I wonder if you can, I know you kind of touched on this a little bit about decision makers, but what are some of the challenges when you're trying to move a modernization or a transformation through this system?

Yeah, there's clearly some challenges. First of all, you know, all the airplanes in the sky are not at the same level of sophistication. So you take the most modern Airbus or the most modern Boeing right now, those airplanes know so much about themselves, all the electronics that's on board and how they communicate, what they can communicate, to whom they can communicate are, you know, state of the art.

But they may be flying next to someone's private jet that's 12 years old. It doesn't have any of that equipment on board. It doesn't have the same stuff. So, I mean, we saw that originally with ADS-B, the automated independent broadcast system, which allows you to see other aircraft and they can see you. It tells, you know, there's traffic control where you are with a lot of data.

And so we said, well, everybody should get that. Well, that's great, except if you own a Cessna 172 that you paid $40,000 for and it's still over your life and somebody says you need a $25,000 piece of equipment, that's going to be a problem. And, you know, I mean, even if you've got a $200,000 or $300,000 airplane, somebody says you need a $40,000 piece of equipment.

What's it out of reach? And so what do you do? Then you just don't allow them in the airspace? You know, best equipped, best served is an old phrase. And, you know, if you have the equipment, you can come in here. If you don't have it, you can't.

You get away with that in Atlanta and O'Hare, but a lot of airports, people want to go in and out of those airports, and they can't afford the equipment. So the good news is the advancements in technology and microchips and all that stuff, the equipment is getting less expensive and better. But still, you've got a design assistant that works on all the airplanes in the air traffic control system, and yet all those airplanes aren't equipped at the same level.

That's a good segue. Bill, I wonder if you could kind of bring us up to speed on some of what's been done in recent years to modernize air traffic control and what technologies we're working on. I know we just did another podcast a few weeks ago, but maybe you could give us a good summary here. Sure. So fast forward from 1956 to 2003, Congress passed the Vision 100th Century of Aviation Act,

which established a joint planning and development office, which combined the FAA, and I believe NASA was a part of that, and other federal agencies. In 2004, the JPDO produced the Next Generation Air Transportation System Integrated Plan,

otherwise known as NextGen, which is kind of the paradigm that our air traffic control system has been evolving through ever since the early 2000s. I guess I would kind of try to describe the progress of that effort along the lines of communications, navigation, surveillance, and then the categories of automation,

And another project of NextGen was SWIM, the System-Wide Information Management System. In the category of communications, the FAA implemented what's known as Datacom, and that's the ability for text messaging communication.

between pilots and controllers. And everything I've heard from both sides, from both pilots and controllers, is that they really like Datacom. So according to the FAA's Next Gen Annual Report of 2024, Datacom has been rolled out to... It started in 2016 with tower service and the use of text messaging for departure clearances.

And it's now currently available at 65 different airports. And it's being deployed to the En-route centers. There's 20 en-route traffic control centers across the country. And I believe all but

Two of them now have been equipped for Datacom with an increased message set for route clearances and things like that. So what that does is it's much more efficient communication between pilots and controllers. It eliminates errors.

any misunderstanding or congestion on VHF radio channels. And it's basically uploading messages right to a flight management system for the pilots to read. So both sides of that equation really like data cam. And the area of navigation, the FAA system,

designed a number of performance-based navigation departures and arrivals at runway ends across the country. I don't have a number on that, but it's in the hundreds at least. And it's enabled by the Wide Area Augmentation System, which is the FAA's satellite-based system for correcting GPS data

signals down to much more precision than you get as a consumer, you know, with your driving directions. And then on surveillance, and Randy spoke about ADS-B, Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast, there's something on the order of 65 to 70 radio stations across the continental U.S.,

that enable ADS-B, which is the automatic broadcast of aircraft's position and other information both to the ground and to other aircraft if they're equipped to be able to accept that information through the process known as ADS-B in aircraft.

And, you know, as Randy said, everybody's got to be equipped for the system to work. Then in the category of automation, the FAA, over the course of this program known as NextGen, they installed the Enroute Automation for Modernization automation platform in Enroute centers.

According to the 2024 report, I'm just looking at this quickly, ERAM has operated at the 20 Enroute Centers since 2015, and its hardware and software are receiving upgrades. Enhancements to its conflict probe and trajectory modeling capabilities were completed last year, 2024, and the flight plan processing capabilities scheduled to be updated this year. And then at the end,

At the approach control centers, the Tradecons is equipped with a different automation system. And this is part of the problem we're currently facing because they don't necessarily talk to each other. And that's known as the STARS automation platform. That's what the approach control platform.

controllers use. It's a very capable system built by Raytheon and it's equipped all across the FAA's, TRACON's as well as some DoD approach control facilities because that was a joint procurement. Then I mentioned telecommunications and this too comes into play in the current discussion

There's currently a contract underway, the FENS contract, the FAA Enterprise Network Systems contract that was awarded to Verizon. That's a 15-year contract. And that's meant to replace the FAA's telecommunications infrastructure. And I believe the FAA telecommunications infrastructure is currently a program of L3Harris, which

And the issue there is it's kind of a backbone built on copper wires, and that's leading to some of the difficulties I'm sure we'll discuss later in this podcast. The SWIM system, the FAA System-Wide Info Management System, it's a software-based, service-oriented architecture system.

in which other stakeholders in aviation can subscribe to that and exchange information with the FAA.

I'm looking at SWIM. There's more than 200 services that are available via the SWIM network. And there's, according to the FA, 51 internal and external organizations now produce data that is published to SWIM that everybody who subscribes to the network has access to. That was an accomplishment of NextGen. And I don't know if this was strictly in Randy's

Correct me, consider it a next-gen program, but just on an organizational basis, the FAA reorganized in June of 2023

to spin off its air traffic control piece to what's known as the Air Traffic Organization. And that's considered a performance-based organization. And the first CEO or COO, I'm sorry, Chief Operating Officer, that was Russell Chu back in 2003. So these are some of the things that were done during this program called NextGen.

And just coincidentally, at the end of the year, as a result of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, NextGen as a program is being sunsetted. This work is not going to disappear, but it's being outsourced to other pieces of the FAA. And as of the end of this year, what is known as the NextGen office is being closed.

So Secretary Duffy in May outlined a plan for ATC modernization going forward. We detailed that plan in a previous episode of Check 6.

And as you noted in that episode, Bill, the January 29th midair collision of a U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopter and an American Eagle CRJ on approach to Washington Reagan National really sent shockwaves across the industry and general public and motivated the current retrospective of the ATC system. We've written a few pieces about these events over the last weeks and months and the plan going forward. So I'm hoping to get kind of our reactions, your our perspective on the plan.

So there's a couple of things and I'll pull Randy back into this again because he has firsthand experience. So there's two things.

I think there's two reactions to the plan to develop a brand new air traffic control system by the end of 2028. The first one is from a pragmatic standpoint, if you're talking about things like replacing copper wires with fiber, if you're replacing things, you're upgrading things from a technical standpoint that will bring more reliability.

there's some feasibility in that. But anytime you're adding new, better, even if it's better technology for better procedures, anything like that is going to require new controller training. It's going to require maybe some equipage. It's going to require, you know,

pilot training, and that is a whole different level of modernization. So when we're talking about this, I think it's important to sort of split those. If you look at the request for information that the FAA put out June 3rd, I think it was, it's mostly the former. It's mostly looking to swap older things with newer things that hopefully will bring more reliability. Will that help? Sure it will.

Will it change fundamentally the way air traffic is controlled and airlines manage their operations? It won't.

And I've had several readers that have chimed in even well before this issue came up, and they have said the biggest issue that we have is that we don't utilize all of the capabilities in terms of things like required navigation performance as capable as it could possibly be, even if you're retrofitting older airplanes.

We don't take a dynamic routing, 3D and 4D dynamic routing. So an airplane gets onto the taxiway at this time, and you're looking at everything that's happening between where that airplane is and where it's going, and you're making adjustments along the way. It's possible, but it requires a shift. And like Randy said and Bill said, it requires everybody to be on the same page. Yeah.

So one thing I wanted to ask Randy about, how much does industry, whether it's the airlines or maybe pilots, how much can they influence the progress or lack thereof of an initiative that's going to bring a major change to either procedures or equipment? It's a great question. The carriers, I mean, fundamentally, let's just say

Cut to the chase. The carriers, anytime you can lower the en route time, you're talking fuel, you're talking engine time, you're talking crew time. So if you can take five minutes off of every flight, the airlines would be all for it. Now, how much is that going to cost? Is it going to be offset by, well, we saved all this money, but we spent a fortune saving five minutes.

So you've got to find that balance, I think. There's a number of groups that I think have done a good job. If you go through the alphabets, whether the NDA, ALPA, these groups, I think they put folks in there that are clear-headed and they understand the systems and they're trying to get to the right goal from it. But

You do see some resistance, a lot of training involved, a lot of equipage involved. And you don't just snap your fingers one night. We were doing this up until Sunday at midnight, and then Monday we're going to start doing it completely different. It's going to be a transition as you shift over to it. Typically, you see a lot of the innovations change.

especially in your post-control world, take place at the Kennedys, at the O'Hairs, at the Atlantas, the busy, busy places where the ability to move traffic. Look at the departure routes out of Atlanta. It's just breathtaking how the five different runways, they disperse themselves. Those are big steps in the right direction. It allows a lot more traffic to move.

But, again, the other side, it's not going to be cheap. And it's got to be evolving. I mean, we still, I still chuckle when I look at, when you look at where the air traffic control centers and where visuals, you know, we had BOR stations and everything. They're the same places the bonfires were for the air mail pilots. These are ancient places.

and nobody has moved, you know, come on. There's more efficient ways to get from A to B. And we don't need a point on the ground. You could take an airplane today

A sophisticated airplane could take off in Kennedy and file a flight plan that has no regard with anything on the ground. It's got to go to the best altitude. It's got to find the best wind. It's got to find everything to optimize the best route it can fly, the fastest, least amount of fuel between A and B. And does it go over all of these stations? No, it doesn't need to.

Does it now? Yes, it does. Yeah. We've got to give up on that. We've got to go, you know, to, you know, the original next gen thinking was almost free flight. You know, right. Just go. And you'd have the best route. And you say, well, everybody can't do that. Well, in today's computer world, yes, you can.

We'll separate you. And the beauty of that type of separation is you've got two airplanes a thousand miles apart and they're going to cross somewhere. Change one of them one knot.

and you got the clearance. You don't have to put them in a holding pattern while this one goes by. You can change speeds or change altitudes. For 200 miles, just climb up 1,000 feet and then go back down or back up. All of this is possible, but again...

And how that happens, maybe you're going to say that can happen from 31,000 feet and above, and you've got to have the equipment to do it. And best served will be best equipped. But that's how it's going to get introduced, I think, into the system, that you're going to have some boundaries that the more sophisticated equipment, the navigation capabilities on the airplane, coupled with technology,

your traffic control ability to monitor and provide the separation all have to come together. So it could be done, but it's out there a ways. And, you know, 2008, let's hope.

You mentioned free flight, Randy. I think even before NextGen, that term was coined. We were talking about free flight where pilots could choose their own optimal routings and kind of self-navigate. And air traffic control was just needed to land airplanes, basically. That's right. I mean, the idea would be if you just let the airplanes –

You know, I chuckle that we still put balloons up in the air every six hours or something. That's all that's left. Every airplane, well, I know Southwest, and I'm certain it's true at United, at Delta. The airplanes, I mean, they know exactly where they are. They know all the effect of the wind on them. They know precisely what the temperature is, that wind direction. All of this is available right now.

not what it was four hours ago, right now. And, you know, the ability to put this information into a package to help people better flight plan, you could do it within your carriers, but, I mean, one of the-- we'll eventually get to the system where everybody's gonna have access to that data, and you're gonna follow a flight plan, and you'll know, you know, if a butterfly crosses your path, it'll-- "Whoa, a gust," you know? It's that sensitive, so-- but it's capable.

We just have to have the equipment that will optimize the capture of the data and the use of the data to the effect of best end.

I don't think that that is all coming by 2028, just to be clear. Yeah, well, HUD is a realistic timeline. I mean, talk about all these pieces coming together. I mean, before you can set a timeline, I think you have to have a plan. And I don't think we have a plan. And I think that we have other ancillary issues that don't necessarily directly relate to air traffic control, but that have an influence. Randy mentioned Southwest.

If you're a Southwest Airlines fleet planner and you are looking at what I need to equip my aircraft with for something that's coming in, let's say there was a deadline of 2025, something relevant.

They would have said, okay, we're going to have a bunch of 737 MAX 7s and a bunch of MAX 8s with this stuff on it. We're not going to have to put it on all of these 30 or 50 or 80. Christine, you know this because you cover all these 737-700s because they're going to retire. Well, lo and behold, we have what's been going on with Boeing and airplanes that were supposed to be certified and delivered four or five years ago are still neither.

And so you're sitting there at Southwest Airlines and you've got all these airplanes that no longer can do what they were supposed to be able to do. I mean, think about the ADS-B deadline that Bill talked about.

So that, if you're looking forward, something like that just becomes another thorn. But I think the bigger picture is getting agreement on what does everyone need and who is everyone? Does everyone include business aviation? Do we include the GA people? What do you do at airports where you have all that sort of mixed traffic? I think it's a big challenge. And one thing we tend to forget in this country is our general aviation population. I mean,

And you don't have even the other countries that are, you know, that are, you know, first world with better ATC systems and all that. They don't have near the GA influence or size that we have. There are some.

But I mean, it's just it's it's it's not even comparable. And so you have to at least factor that in. Does it become a limiting issue for the airlines? That's you know, that's certainly above my pay grade would make for interesting stories to write. But those are all factors that that complicate our situation a little more than than than some other situations, at least in my view.

I spoke to a regional vice president with NATCA, the National Air Traffic Controllers Association, and this question did come up. You know, what can be, you know, what can be accomplished in the three to four year timeline that the Trump administration has laid out for this?

And he said, you know, the two biggest things that he would recommend are to fix the FAA's telecommunications infrastructure to, you know, to fast track that conversion from copper wires to fiber and the use of Internet protocol as the, you know, the data exchange infrastructure.

And two, something the administration is doing is to supercharge the hiring of air traffic controllers. You know, again, this is a NAFTA perspective, but those are the two, you know, those are the two kind of pillars that they would recommend to kind of make this happen, at least within the next three or four years. One, just a side note, one thing that is helping them greatly, there's now approval. There's about 70 schools now.

colleges in the United States that belong to Abbey, which gives them, you can train there and you get a reduction in your flight time to get your ATP. But those schools are now getting approved to have controllers training

And you can take somebody who, you're going to go to college anyway, and hey, I like that idea. You leave there, you are literally ready to go start in a basic tower. I mean, a very simple tower. But the two years has been eaten up in school. And it's got, I mean, 70 universities can produce a heck of a lot more ready-to-go controllers than two training centers, one in Oak City and one in Atlanta City.

I mean, you just can't flow that many people through that small a window and letting the colleges do it. And by the way, they have a curriculum they have to follow, and it's just as rigid as the one the FAA has. So that's a point of optimism I just thought I would throw out there. Utilize what you can utilize, and if it helps you get to the goal line, use it.

And the FAA is also introducing a simulation capability for air traffic control. I think those are based at towers. And that's supposed to expedite the on-the-job training period. It's supposed to streamline that by a year. I think that it's something 18 months to two years of training.

on the job training at a facility to have a facility rating or certification, the simulator is gonna be able to expedite that by a year is what I've heard. - Well, at simulation, I mean, there's an old adage for pilots, a good pilot's never a surprise pilot. Well, a good controller's never a surprise controller either. If you've seen it before, it's not a surprise.

And simulation allows you to have scenarios that you would never, I mean, A, you would hope it wouldn't even happen, but they do. And if you've had a setup where somebody suddenly taxis out onto the runway in a scenario that's simulated, you'll know what to do. You will have seen it. And you have a much better feel for the reaction required. And if you did it wrong, okay, fine, let's back up. Let's do it again. Yeah.

You did this. See what happened? That won't work. You got to do it this way. Fine. That's why we simulate things. And I think simulators are incredibly valuable in flight training and they're equally valuable in control over training. Sean, do you want to go in a little bit about what our readers are saying about the overall plan?

Most of the feedback really, but goes into this, you can change the infrastructure, but until you start changing the procedures, I mean, here's one that references another RTCA committee that was done, that met and came in the recommendations over 20 years ago. And they talked about the high altitude redesign program, which I

I remember writing some about it. I don't know if Randy may remember that. That was, it was, again, it's, and it's, they talk about how, look, we've done a lot of, we've deployed various new airspace capabilities, including RNAVQ routes, navigation reference systems, special use airspace mitigation, and more flexibility, but without

But funding, consistent funding and a plan, we fell short of some of the goals that were laid out in the RTCA report recommendations. I think it just comes back to fundamentally we're trying to improve a system that still, it's not DC3 era, but it's...

old and you know the you can match the vors to where to where bonfires were before there were beacons you know and the beacons are where the bonfires are until you come up with a fundamental change in how we're going to approach this we talked about this on the other podcast you can only modernize so much if you're not and there's no fleet equipment nothing's changing on the fleet

So we're not adding any capabilities. So, I mean, I failed to see. I mean, I go so far as saying I failed to see how anything they're talking about doing in the air traffic control, in the new air traffic control plan, the brand new air traffic control plan, would have changed anything that happened at DCA on that night in January.

It wasn't a technology issue. It was a procedural issue, at least in my view. And the NTSB will focus on their probable cause. We'll start with the acute mistakes that individuals may or may not have made.

maybe some controller communication error, maybe some error by the pilots and the crew and the Black Hawk. But fundamentally, it was the procedures in place or the lack of procedures that allowed that scenario to happen.

happen. Nothing they're talking about changing the next three years is going to change that. They've already changed it by banning helicopter flying, which is great. However, they had done 40 years of that kind of flying without having this kind of accident. It doesn't mean it was safe, but it doesn't mean you can't do it either. So,

So it's really about changing how things are done. That's how real change is made. And nothing that the administration is talking about is going to change any of that, and you can't change that in three years, honey. Well, and some of that, Sean, in all fairness, there was some common sense that was out the window. So we want to teach helicopters how to fly over a river at night. Did we have to do it at National Airport, one of the busiest airports in the country? Couldn't we have gone up to Potomac about 30 miles and done the same training? No.

It's a whole different podcast, Ray the Babbitt. That's a whole different podcast, and it may be one that's worth having. But you're absolutely right. There were a lot of things. I mean, the first thing I looked at when I started reporting on this, I asked pilots to send me all the special stuff that they have to learn about helicopter flying. When they're flying in the DCA, send me everything that you're told about all the helicopter stuff. We're not told anything. I said, what?

I equated, you know, one of my grandkids asked me, he said, was that necessary? I said, that would be like teaching kids how to, you know, they're going into the first grade and we want to teach them to use the crosswalk. So we're going to go out on the I-95 and train, you know, come on. Right. Well, and nothing, you know, again, they've addressed this with very acute things and the bigger, you know, turning on, if the helicopter had an ESB on, it would have made a big difference.

Because nothing in the CRJ would have picked up that ADS-B6. Nothing that they're required to have anyway. Could add an iPad up there playing around with it, but that would not have been...

You know, you wouldn't have sterile cockpit if you're playing around on your iPad to look at ADS-V, right? It was one of those classics, you know, somebody I love to express when we talk about accidents that, you know, every now and then all the holes in the Swiss cheese line up. It doesn't happen very often, but when it does, look out. And that's what happened. You had a whole bunch of things, any one of them removed from the equation, no accidents.

Well, and to that point, you hear a lot of references today to impending one of these times we're going to have an accident. And that midair collision certainly was a stunner because a midair collision in this day and age involving an airliner, very surprising. And you knew at some point there was going to be another major accident, a major 121 passenger accident, as they say, the first since Colgan, even though there have been a couple of others in there and some cargo ones too.

The idea that the runway issues that we've been talking about or the ATC issues are going to lead to, you know, something is going to happen. You keep hearing people, not necessarily in the trades, but outside saying it. They were saying the same things back in the editorials in the 1950s. And lo and behold, they were right. So far, we haven't been right. And that speaks to how well we keep those Swiss cheese holes misaligned with everything that has gone on sort of around or, you know, around the system to help make it safe.

So, I mean, one thing that I'd like to ask, because I know that we've all done a little bit of reading and brushing up on our history, right, in the weeks and months

months months leading up to this podcast but as you as you say sean it feels a little bit in some ways um not always but as like kind of a here we are again moment reading some of the things that were said in those editorials back that back then sound like you know things that we have been writing today or could be writing today um so i'm curious to kind of pick your brains i mean in your reading and in your brushing up on history did anything pop out to you um

you know, from that time period in the mid-50s that we should be keeping in mind now, now that air traffic control is again not keeping up with the demands of the system. Did anything come out to you as, you know, this is something that could be relevant again today? I mean, there's a couple of things that I'm aware of that don't help

as we move forward. You know, we came up with this grand idea that we would separate the air traffic organization from the FAA. I'm not on either side of the argument, but don't start down that path and get substantially into that path and then change your mind. And we've had too many times where we have a big heading change, start on a plan and we do this. Whoa, this is better. Let's cancel that and we're going to do this one.

We wind up with a lot of plans, you know, that are put in the shredder, and they're not... You know, we need to have more certainty to the long-range plans, and it needs to be, you know, capable of evolving. Have we discovered the latest stuff we're going to use? Not. I mean, I guarantee you, a year from now, we're going to find... You know, you'll just put this little button up on the radar on the airplane, and it'll know right where it is and tell everybody in town. I mean, the stuff...

It's just going to get better. And we need to design systems that are perfectly capable of accommodating and adapting to these changes as we come along. But we pour concrete, and this is what we're going to do. And two years later, we finish it up. Meanwhile, there's been two years of technological advances that would have really improved the system.

But we've poured concrete back here. So that would be my biggest suggestion is let's have a long-term plan, but have that plan be flexible enough to adapt to changes in technology as they're discovered and implemented.

On my part, you know, the ongoing theme I've seen throughout the decades is lack of funding stability of the FAA. And I would place the blame squarely on the shoulders of Congress and the dysfunction of, you know, the political parties that make up our Congress. I think they should just, you know, get out of the way, right?

that the FAA should not be subject to the annual appropriation cycle of Congress and kind of let the experts do what they may. And I believe some of the Airways Trust Fund that's kind of behind the funding of the FAA is also kind of peeled off for other projects as well. So, you know, the money that the users of the system pay

That goes into the airways. Trust funds should be used directly back to fund the system and to maintain what the FAA is able to do. Well, you also have a minor issue in there that the DOT, the Department of Transportation and Round Numbers, has somewhere between 65,000 and 70,000 people in the DOT.

50,000 of those are the FAA. And so you're one of the children of, you know, with eight other departments that, you know, everything's got to go through the Department of Transportation. If there was ever an argument for a standalone agency, it would be, why don't we just move that one over, you know, and everything, if you find rails, pipe, all that, that's, let's just all, but this is a very large organization. And to have to get approval, you know, for everything you do is, you know,

probably slows the system down a little bit. I'm not advocating that it may be... There may be ways to better handle it, but it just always seemed awkward to me that somebody that is three times bigger than everybody else in the DOT put together still is under the DOT, but that's just a personal comment. Right. Now, and the DOT, of course, is...

cabinet level department so they get their leader changed with every administration. They tried to ease the impact on that for the FAA by bringing in

five-year fixed terms for the administrator, but it seems as though that the political influences around that administrator position makes it impossible or difficult, I would say, to serve when you're appointed in one administration and then the parties change. Political challenges with being a holdover from a previous administration that caused both of the last two permanent administrators to say, you know what?

This isn't as efficient. I'm not getting it done the way I thought I could get it done. But similar in terms of the bigger picture, Christine, to answer your question, it's the how. It's the lack of a firm plan. You've known for decades what needs to be done. And in most cases, even the technology has been there.

But there hasn't been a handle on the how, whether it's funding or whether, you know, back in the 50s, it was who was going to do it because there wasn't an agency to do it.

But it's amazing to me that you have all of the solutions. It's not like we need to invent a lot of new things to get this done. Some would argue we don't need to invent anything new to get this done. You just need to put some boxes on airplanes and train some people and get some systems deployed. Not easy. I mean, not simple. And to Randy's point, you have to do it in a way where it maintains flexibility. There's flexibility maintained. But just haven't been able to come up with a how.

And I applaud the current administration for their efforts to get something done. And hopefully they'll make it blackouts less frequent and things more reliable. But in terms of getting to a better how...

I don't think we're any closer than we've been. I mean, we're going to have to leverage next gen as much as we can, which we talked about that last podcast. I think it's shift. It shifted from a free flight to let's take advantage of everything that all the airplanes already have to the max. And let's just do that. I think is that fair, Andy? Is that fair to say that sort of shifted along those lines in the around your time? I'm not saying you did it.

So, but a lot of parallels to me, you're right. A lot of these words that we've written, these editorials, I mean, they could have been written, you know, take out some of the death totals and they could have been written yesterday. Joe, Joe and Selma could have written them. Our capable current editor.

We're somehow at the end of our hour already. So I guess kind of as a final wrap up, Randy, drawing on your experience from both industry and Washington, are there any final thoughts kind of on the ideal path forward here? And maybe it's in the headlines and coverage and commentary around ATC this year, but

Is there something that you feel hasn't really been said or is critical to understand? I wish that as we move forward, obviously you have to approve these monies. And I know there's a huge concern about excess spending and all of that stuff. But in the priorities of the world, we're moving. At any given moment, there's 7,000 airplanes up there moving, 2 million people a day.

And in terms of safety, I mean, it's unprecedented. And we need to get past being political about these things and being practical about it and put in place what's best for the system, not what's best for the OMB or somebody else who's going to, you know, cost it out and say, well, that's just too expensive.

It's never too expensive. If your child is one of those ones in the wreckage, it wasn't too expensive. So, you know, I think going forward, let's look at actually fixing the system and worry a little less about the politics. There's other places you can do that and, you know, go from there. Thank you, Randy.

And thanks for joining us today. That is a wrap for this episode of Check 6 Revisits. Special thanks to our producers, Jeremy Karuki, Corey Hitt, and podcast editor Guy Furnio, and to Bill Carey and Sean Broderick. For links to some of the things we referenced today, including our archive, check the show notes on aviationweek.com, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

To delve into our archive for yourself, Aviation Week subscribers can head to archive.aviationweek.com. If you enjoyed the episode and want to help support the work that we do, please head to Apple Podcasts and leave us a star rating or write a review. Thank you for listening and have a great week. College students qualify for free digital subscriptions to Aviation Week and Space Technology.

That includes access to our archive, a valuable resource that contains every issue back to 1916. To sign up, go to aviationweek.com slash student.