The Six: Recovering the Lost Story of the Titanic's Chinese Survivors

Barbarians at the Gate

Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

Hello and welcome to another edition of Barbarians at the Gate. This is Jeremiah Jenny broadcasting from the city by the lake, Geneva, Switzerland. And with me, my co-host, David Moser. David, how are things in the steamy town of Bangkok on this fine day? Yeah, I'm doing quite well. Getting even more accustomed to this place. My wife has had some days off. And I was thinking in a previous podcast, we talked about culture

And it seems like this has been my third extensive trip or visit in Bangkok. And I'm really feeling like I'm actually getting acclimated to this place. And one of the things that took some getting used to is the de rigueur, absolute obligatory

Sawadika, this greeting that they give to everyone at all times and goodbye and hello. And even if you've just walked in and out of the door six times, they will still greet you every time. And I've been hesitant to sort of get into that.

what seems to me excessive kinds of polite acknowledgement of the comings and goings. But I now tend to do it instinctively. It's feeling quite normal, natural. And I think when I go back to Beijing, I'm going to feel like, hey, why are people being so rude, not even acknowledging my existence? So I think I'm

I'm going native gradually, but I thought of culture shock when I made this realization. Well, from a linguistic perspective, isn't there a masculine and a feminine form of that greeting? That's right. And I try to make the distinction. I think I'm doing it right. They sort of agree with

with what I'm doing, but I can't hear it myself. It's too subtle, but I do try to do it. I know it must sound very non-native to them, but I do my best. Yes, it's in the ending and it's in a lot of endings have a masculine and feminine component. So yeah, another tonal language that I probably will never master. It's taken me so long to master the four tones of modern Mandarin. Nevermind you get down to Cantonese or Thai where you have rising, falling, lower, higher,

backflip triple gainer landing in a double axle tones that I probably will forever get them wrong. Let me, let's talk about our guest though, David, because it's five o'clock in the morning where he is in the wonderful state of New Jersey. Uh,

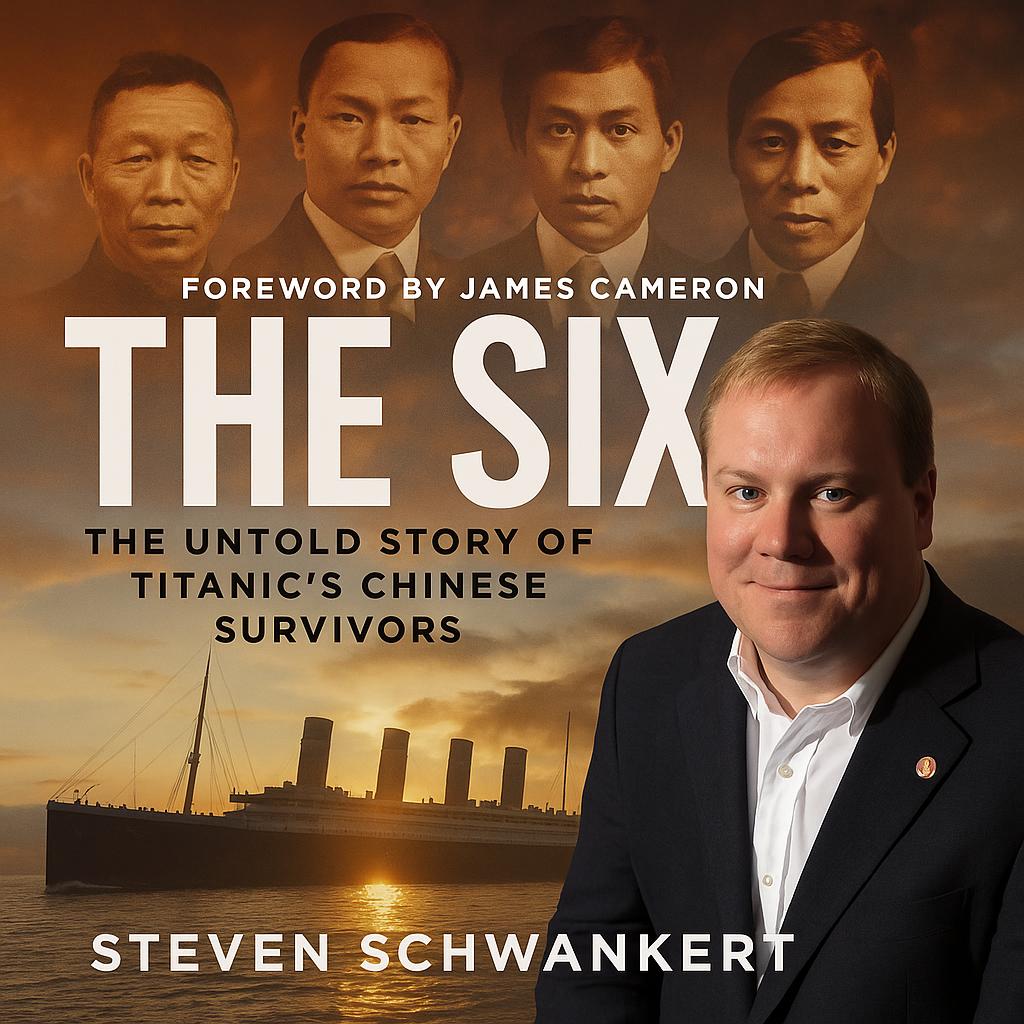

Steve Schwenkert is no stranger to those of us who have lived in Beijing. He himself is a 25-year veteran of Greater China, and he is also the author of the new book, The Six, about the Chinese passengers who survived the Titanic disaster in 1912.

And while the Titanic story has certainly been told countless times in many ways, the experience of these Chinese survivors remained largely unknown until Schwenkert and his team brought their story to light. In his book, he explores how these six men survived the disaster and examines their experience in the aftermath where they faced discrimination, deportation, and erasure from historical records.

What emerges is not only a gripping survival tale, but a sharp look at racism, immigration, and forgotten transnational lives in the early 20th century. Steve Schweinkart is an award-winning writer and editor, a fellow of the Explorers Club, a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, and the founder of Sino Scuba, Beijing's first

professional scuba diving operator. Steve, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for joining us today. Why, thank you, gentlemen. Thank you for having me. I have to say, I enjoyed the documentary when it came out. You worked on that with your frequent collaborator, Arthur Jones, and it was a real treat to read

the book that's been recently published as well, because it gives us a little bit of behind the scenes of the research that maybe didn't make it into the documentary. But first, I really wanted to ask you, what are the origins of the story? What drew you to a story of the Chinese survivors of the Titanic? It feels like there's been books written about every conceivable configuration of Titanic passengers, but somehow the Chinese contingent never quite made it into the popular consciousness. How'd you find out about them?

Well, Jeremiah, that's really what drew us in. Obviously, there's a lot out there about various folks that traveled on Titanic, whether it was the first class passengers or different segments of third class passengers, the Irish. You know, especially in the last few years, there's been a bit of an explosion of the examination of, let's call it, under-

under examined groups on Titanic. You know, even though we know about the glitz and the glamour of Titanic and that for the first, let's say, 80 years of its history or so, it's really the first class passengers, the John Jacob Astors and the Molly Browns, really named Margaret Brown, but

But, you know, the Molly Browns, those were the people who really got the attention. For Arthur and me, we started looking at something else. We were working on a separate research project. We were looking at a Shanghai shipwreck, Civil War era, Chinese Civil War era, of course. When we thought about how to tell the shipwreck story, especially a large-scale maritime disaster, I said, "It's no problem. We're going to compare it to Titanic."

because after Titanic, the James Cameron film was released in China in 1997, we knew it would be a story that people in China and people internationally would understand. It was just a metric that we could use easily to compare in terms of size, number of passengers, loss of life. That just all made it very easy. So at that point I went back to my Titanic bookshelf, which I happened to have,

And I started to reread some of the classics like A Night to Remember. But I also went online and I started to look for, you know, what kind of new research has been done on Titanic. I wasn't looking for anything specific, but I just sort of wanted to understand how is Titanic discussed now as opposed to maybe 10 years ago, 20 years ago. The other thing is that in 2012, we had the...

100th anniversary of the sinking of Titanic. So obviously that kind of created a lot of light and heat around it, drew in a lot of attention that it doesn't get otherwise in the average year. You know, the first two weeks of April is always Titanic season when we have new specials and new interviews and so forth, people claiming new discoveries.

So when in this particular case, I went to a website known as Encyclopedia Titanica, which is really just a compendium of all different kinds of stuff. There are biographies of passengers, some vital statistics, just whatever you might be interested to know, plus message boards, new research, background materials, all kinds of things. So I know that

I had heard of Chinese passengers being on Titanic before, but at least before us, there wasn't a lot of information there. It was just sort of some stray, it was like a stray sighting. You know, it was J. Bruce Ismay who owned Titanic. He mentions Chinese passengers because there were some in his lifeboat. There were, you know, just sort of these sightings of Chinese men aboard Titanic and then some very libelous comments afterwards made to newspapers. But that was really all there was.

And this time when I looked at it, I thought, but why don't we know more about them? You know, why is this so under-documented? I always get, I get picked on for picking on the Irish, but it's just because I'm using my own heritage. Despite my German last name, I'm more Irish than anything.

But, you know, we know so much about the average Irish villager that was on board Titanic. We know so much about the Americans. We know so much about the British. Why don't we know more about the Chinese? How is it possible that these six men, you know, six out of eight survived? There were eight Chinese passengers and six of them survived. That's, you know, a very small sample size, but it's kind of an incredible survival rate. How is it that we don't know more about them? How is it that we don't know more about their escape?

What could that tell us about the Titanic disaster overall? And so those were the things that really sort of caught my attention and made me start to think, gee, this is maybe even a better story than the one that we're working on. It started there and it started to build from that point.

When you pitched this idea, did your collaborator, Arthur, agree with you about the potential for the research into these passengers? Well, as I'm speaking on a podcast that features two collaborators, I'm sure you can understand the dynamic when...

One of you thinks an idea is a great one and the other doesn't really share that. You know, Arthur, we were six or seven months down the track on the other project, including interviewing survivors from that shipwreck and, you know, really starting to make a little bit of headway. And so at that point, no matter what the subject was, it was not really going to be met with an immediate embrace. And I, you know, that's normal.

But in our case, I think Arthur, like a lot of people just thought, you know, what else is there to discover about Titanic? What else could possibly be new in terms of telling the story? You know, what could we possibly do that's fresh? Why would we want to move away from a story that's original and start to examine, you know, something on Titanic that potentially is not nearly as exciting. So it was not met with, with, you know, it wasn't a happy first conversation, um, but

But what I did was I started to suggest materials to Arthur. Okay, here's how we tell the story of a large-scale maritime disaster. Because the previous documentary book that we'd worked on, Poseidon, was also a maritime story. But, you know, you're only talking about the loss of life of maybe 50 people. I don't want to diminish that. But just from a storytelling perspective, it's a little different. The impact is a little bit different. So I started to hand him A Night to Remember and some of these books about Titanic and

to put him in a Titanic mindset. And then, you know, over time, I'm kind of mentioned, you know, oh yeah, Chinese passengers, the Titanic, very interesting, but we'll, you know, stay the course on what we're doing. And finally, after about another six or seven months, he was in Beijing one evening. Arthur is still based in Shanghai. I was always based in Beijing. And I said, look, you know, this is the story. Okay.

Okay, I don't want to turn away from the original story either. But you know that this is the story. We have to do this now. If we don't do this now, somebody else is going to find it. And then, you know, someday we'll take turns kicking each other in the rear end because we had it in our hand and we let it go. I said that the other shipwreck thing, we can come back to that. It will be there.

But this we have to do. Somebody is going to stumble on this. Somebody may be working on this right now and we don't know it, but we can do this. So let's spend the next 90 days and we'll try to disprove the story to ourselves. In other words, let's spend 90 days and we'll do the opposite side, that there's no story here, that this isn't worth pursuing.

And if at the end of the 90 days we've come to the conclusion, okay, there's nothing here, then we just go back to what we were doing. But if we discover that, okay, we can take this forward, there is something we can do on this, then we'll go in that direction. So finally we agreed.

You document very well the rather grueling task of gathering the information. It's quite a detective story, in fact, just tracing the history of these six men who actually, you know, had to expend a lot of effort to hide their identities at times and then later on to prove them and also counting the...

The vagaries of various romanization methods that you'd have to match up. It's almost impossible to piece together them because there's so many different, sometimes just developed ad hoc on the spot, just spelling methods. And then also, I guess, the reticence of the Chinese survivors, because as I hope that we get into, they had reason to be hesitant to admit that they were survivors of the Titanic because...

because of all of the false narratives and stories that they had stowed away and that they had dressed up as women to survive and so on and so forth. So six survivors who might have been very willing to come out and tell their stories and even get famous for it didn't dare do so.

because of the immigration status and of just being Chinese at a time when there was lots of racial animosity. Maybe can you just say what it was like to go through that process of disentangling these narratives and actually being able to find documents based upon all these problems? So we started out with the list of names. We started out with six survivors' names. And we decided...

you know, almost immediately we were only going to focus on the survivors because we thought this is going to be a difficult enough story to tell, um,

You know, if we try to include the two men that didn't survive, that's gonna be even more difficult. Their story is already quite brief, you know, at least in terms of the historical record. Let's not even go too far trying to find that, except we thought that one might be a brother of one of the survivors. But we just... That's how we got the title "The Six."

I saddled us with that name early on. You know, if we were to do it again, we might do it a little differently. I might not fix us with a name that required us to round off six full stories, but...

We started off with the list of names, and what we were trying to see was what does this tell us and what doesn't this tell us? Because these were Romanized names, first we wanted to see what, you know, can we deduce from this what dialect they spoke? Of course, 1912, probably they're not Mandarin speakers. They're probably not coming from the north. They're probably from somewhere in the south. But are they speaking Cantonese? Are they speaking Hakka? Are they speaking Toisan? Is there anything that these names can tell us?

We're also trying to figure out where did these names come from? In other words, are these men walking up to a White Star Line ticket counter in the UK and stating their names and whoever is behind the counter is writing them down? Are they coming from some sort of official travel document? Is their employer, the Donald line, is the company giving the names? You know, what does that tell us?

So something that I've felt for a long time is that it's for researchers, it's, you know, on the one hand, we have this great advantage now where we can access online libraries almost instantly, Google Books and just general Google searches. And now with the advent of AI that's connected to the web, you know, we can do so much from wherever our desk exists.

happens to be at that moment. I think it's really important whenever possible to go and find the original documents. Go to the archive and get the original documents. Go to, you know, wherever the repository of those papers is.

because the original documents really tell you a lot. And I think that's something that's being lost in a digital age, in an age of digital search and digital research, because sometimes, you know, you see things on the document that you don't see on the copy. You see references

notes that are written in the margin that didn't make the scan because they didn't fit into the frame. When they give you the file, sometimes there are things that fall out that are not part of what's been scanned. So I really recommend that as much as possible. In this case, seeing the original document, the original passenger list, the first name on that list is

It had been reproduced for over a century as Ali Lam, A-L-I, like Muhammad Ali. And when you look at it on the paper, especially for anyone who spent time in China, you realize that

It's Ah Ah Lam. So in other words, it's not a momentous discovery, but it was something that really framed where we were going from that point onward, because now we realize, OK, this is a nickname. Ah is an appellation, you know, often still used in southern China. And so all of a sudden we realized that we're searching for Little Jimmy in in the historical record. We're not looking for official names or at least not in one case. That was interesting.

On the one hand, it was welcome information, but also we suddenly realized that our task was going to be much more difficult. The other thing that the names list told us is, although now in China it's very common for people to have two character names, let's call them like Wang Jun, where you have a surname and a given name and there's no generational name in between. But certainly in 1912, that was not commonplace.

common. And in fact, we found it quite strange that all six men would only have two names. So then we think, well, what does this mean? Is this a surname and a given name? Is this a surname, a generational name? And then the given name is cut off. You know, what is this telling us? And so we realized from a very early point that working with the names and trying to establish these men's identities was going to be one of our most difficult tasks.

The survival rate of the six is something that we mentioned in the top of the show. It's something that you've mentioned in your book and in the documentary that six out of the eight Chinese passengers survived. It's remarkable, first of all, because there were many other groups for whom the survival rate was not so high.

And also because these were third class passengers, so they were presumably in a part of the ship that would be least convenient or least prioritized in the event of an evacuation. Why do you think the survival rate was so high for this group? Was it because, as you mentioned in the book and documentary, they had a background in

As sailors, they were familiar with boats or was there another reason why these six, at least six of the eight, were able to affect such a miraculous escape? I think that's certainly part of it. So third class men who were traveling without families were courted in the bow. And I think that that really worked in their favor. Now, there were so many rumors that surrounded the Chinese men. Were they stowaways? Were they part of Titanic's crew?

you know, why were there Chinese men on Titanic in the first place? Because frankly, when you think about it, it's a little bit,

uh unexpected it's not that there there shouldn't have been chinese passengers on titanic but it's definitely unexpected you know going from the uk to the us that was not really the easy way to get to the us at that point so they were professional mariners they were they were seamen uh they worked in the engine rooms of ships sometimes as cooks uh but they had experience on on vessels let's call them not anything the size of titanic but they certainly knew their way around a ship they knew

basic construction, basic layout. So the reason that they were on Titanic was because today we would call it seconding or secondment. They were working for a company called the Donald Steamship Line, which was a cargo operator. There was a coal strike on in the UK at the time of Titanic sailing. Because Titanic had ordered so much of its coal in advance, just because of the sheer size of the amount that it needed to

and also by pulling coal away from its other scheduled departures.

Titanic was able to sail on time. So because of that, Donald Line essentially is, you know, all their ships are stuck in port. They need some men to work on their North American line. So they say, okay, here, we have these eight Chinese sailors sitting around doing nothing at the moment. Let's send them over to our North American lines and they can work there. It's very, you know, even though the Chinese Exclusion Act was very much in effect in 1912,

It's very much like today. So for example, something like 27% of the world's mariners are from the Philippines.

Now, a lot of those sailors are not able to get visas to enter quite a number of the countries that they sail to. However, you can get a sailor's visa that allows you to go into port areas, that allows you to land, to continue working with your ship. In other words, you know, ice or somebody doesn't storm onto the ship and drag you off and send you back. It was very similar then. There was a little bit of monitoring, but it wasn't, you know, it wasn't really a

a very tight framework that was used. So the Chinese men would have been quartered in the bow with the other unaccompanied men. Third-class families were in the back, fathers and men traveling with their wives. They would have been more towards the stern. Now, when Titanic strikes the iceberg, first of all, if you're a mariner, secondly, if you're quartered in the bow, you're going to notice it.

And they were in a lower deck, maybe F or G deck. So actually, they were probably quite close to where the strike occurred. And they definitely would have noticed it. Sleeping, not sleeping, you know, they would have been alarmed by it. Whether they wanted to stay in their cabin or not, they really had no choice. Within about 20 minutes, they are starting to get flooded out. There's water under their feet. They're noticing that something's wrong. Obviously, they would have noticed the engine stopping.

So they would have grabbed their things and gotten on the move. That probably really helped them because it at least puts them in a mindset that there's an emergency and that they need to find a way out. Now, we think that they probably ended up with a lot of the other third class passengers toward Titanic's stern, maybe in a lounge that was in the fantail there, that sort of sweeping stern that Titanic had. There was a third class lounge in

Inside of it, not on the deck, but inside of it. So we think they probably would have ended up there for a while. But between their overall knowledge of ships, especially staircases, crew staircases, you know, what's going to lead upward out of a steerage area like where they were quartered. I think that really helped them.

The thing that really determines at least the outcome for four of the six is that they made a counterintuitive decision that ultimately saved their lives. So if you imagine the latter stages of the sinking and Titanic is at an angle and you have people starting to rush toward the stern and in the James Cameron film, there's the scene of the priest kind of hanging on and people are grabbing onto him and he's praying and so forth.

Most people, of course, are making what seems like the rational decision to go to the high ground, which is the stern, or the highest point away from the water. Our men, at least four of them, decided to go toward the water line and see if there were any further lifeboats there. And that's really what saved them because there were still some collapsible lifeboats that were being assembled. They were able to get into one of those, the same that J. Bruce Ismay, the owner of Titanic, took.

And that's really what saved them. Had they gone toward the higher ground, probably we wouldn't be telling this story. There wouldn't have been enough to have survived to even focus on. So that quick decision really made a difference for all of them. And I think only that little bit of extra knowledge that they had of maritime operations and boats that might be stored on the wheelhouse or

or fastened to the deck. I think that that really made the difference at a critical moment. The survivors who ended up in a lifeboat became...

objects of a considerable amount of public scrutiny and scorn, even though these men were not around to defend themselves because they were forced to move on. Once they reached New York, they were forced by authorities to board the ship they were supposed to board for the Donald Company. But in their absence, their presence on these lifeboats became a source of a lot of consternation

Could you tell us a little bit more about the circumstances around this controversy of the Chinese men in the lifeboats? And also, if you could, would you mind talking a little bit about some of the fascinating work you did with the students and faculty of the Western Academy of Beijing to try to prove definitively once and for all that some of this narrative around the Chinese men in the lifeboats was, in fact, completely made up or was not true?

So while we were struggling with the names and what can the names tell us and what are the names not telling us, and we thought rather than just bang our heads against the wall, you know, for this, for the foreseeable future, what are

What other mysteries around this? What other possible discoveries can we make? What else don't we know about the Chinese men or what do we know or what do we think we know? Arthur and I really like to work on stories where either the story is completely unknown and we're going to tell you the story and we're going to tell you why you should know about it. Or we like stories where people think they know something about it.

but we're going to tell you the real story. And that was sort of what drew me in in this case. You know, there's so much emotion around Titanic, and I'm talking in the immediate aftermath. I'm not, you know, 100 plus years later, there's still a lot of emotion about it. But, you know, imagine that your husband just...

perished in this accident, women and children first or women and children only, you and your child or children are allowed into a lifeboat. Your husband says to you, love you, sweetheart. I'll get the next one. See you soon. And he steps back from the rail and goes to his very gentlemanly death. And then all of a sudden you're on a rescue ship, you're on a lifeboat, you're a

essentially an emotional shock. And here are these four men that don't really look like you, don't seem to speak a language that you speak. You're going to direct your anger, you're going to direct your anguish at someone, okay? And they happen to be a very convenient and obvious target. I don't want to say that people didn't have negative feelings toward

other races or other religions or other groups at that time. But the Chinese men were a really convenient target from people who were still in the process of suffering and grieving and so forth. So I don't want to absolve the people that made those very nasty statements 100 plus years ago. But in context, like any disaster, any plane crash, any building collapse, any anything, the first question is always,

Who am I going to blame for this? Who should be blamed for this? And of course, the correct answer is the White Star Line. But in the immediate aftermath, there was definitely a feeling that if someone survived, someone died because of that. So if my husband isn't sitting here and this Chinese man is, that means that...

You know, using that logic, then this Chinese man is responsible for my husband's death because he took the seat that my husband could have taken or my companion or, you know, whoever it is. So I think a lot of that is born out of emotion of the time. But of course, once it's published in the Brooklyn Eagle, that they were stowaways, that they dressed as women, that they took the seats of family men and others. Yeah.

you know, then, you know, unfortunately it becomes part of the, of the historical record. And then, you know, it just lives on forever and ever. So we thought what really happened, because if you read the various accounts, if you read the inquiry testimony, if you read the letters from some of the survivors, some statements that were made to the press, it's, it's

It's kind of tough to say. And very early on, we engaged with the Titanic community to try to find out what they knew about the Chinese passengers. We didn't really want to tip our hand because we thought we had a good hand to place. We spoke with some of the experts. And I'll tell you that the original, the early reaction to what we were doing was not, again, not embrace one very well-known Titanic.

Titanic researcher who sent us a lot of information. So I'm grateful that that happened. But she or he sent us a note with the research and said, don't sugarcoat this story because you're doing it for a Chinese audience. And I really thought that was untoward. I really bristled at that because that was never our intent. Our intent was to let the facts speak for themselves. That's really where Titanic research is now. The Titanic research up until this point

you know, maybe the last 10 or 20 years has really been he said, she said, and I agree with she, or I agree with he, and here's why. My research indicates that the she said side is the right side, and here's why. You know, the reality is that probably the one group of people on Titanic that is universally loved is the band, because they're just seen as the good guys who go down with the ship.

Depending on whose story you believe, maybe they played to the very end. We don't really know. But even with the band, this group that everyone seems to love, there is still no agreement on did they play until the absolute end? Is that why they perished because they just kept on playing? Or did they stop at some reasonable point and just tried to save themselves like everybody else?

And then what did they play? Did they play August? Did they play Near My God to Thee? What did they play? And there's really no agreement on that. So if you can't agree on those things toward a group that everyone likes, how are we going to agree on anything else? So that's really where the idea of building a lifeboat came from. And I said to Arthur, I said, look, the only way we're ever going to prove what did or didn't happen, or at least what was possible with the Chinese man in the lifeboat, is we're going to have to build a lifeboat.

a collapsible lifeboat. We're going to have to build a full-size replica and put real people in it. We can't build a 10-foot model and stick Ken's and Barbie's in it because the Titanic community will shout us down immediately. Nothing will make it easier for them to dismiss this than to do something like that. Arthur's reaction was...

okay, what do you know about building a lifeboat? And I said, well, that's a wonderful question. And the answer is nothing. And I don't need to know anything about a lifeboat because I'm not going to sit around and build it. What we're going to do is we're going to approach an international school, which, you know, for people that have spent time in China, we know that there's an oversupply of them, especially in Beijing and Shanghai. We're going to approach an international school that has this kind of capability and we're

We're going to let them help us. We'll make it into an after-school project. We'll teach them all about Titanic and lifeboats and this bit of history and give them an opportunity to do a little myth-busting, and we'll pay for it. And that's how it's going to work. Because I've seen this kind of thing before.

taught scuba diving at a couple of different schools in Beijing. And so you know that this kind of thing goes on. So I crossed my fingers and I sent out a WeChat to teachers that I knew. This is not revisionist history. I'm not telling this story now because that's who we ended up with. But I really crossed my fingers that it was going to be Western Academy of Beijing. So Mark Trumpled, who was the design teacher there at the time, definitely wanted to do this

I mean, they were really ambitious. They really wanted to kind of do more than even we wanted them to do. They wanted the boat to float and they wanted the real canvas sides and so forth. And a few of those things kind of fell by the wayside because of budgetary concerns. They went all in and I think they had 20 students, 20 something students who worked on at various points. There were a couple of students who really drove the project. But about a year later, we had a full, I think we had the only full size project.

replica of a collapsible lifeboat, a Titanic collapsible lifeboat in the world. In the end, our version didn't have collapsible sides because the canvas is really kind of expensive. But other than that, it was absolutely 100% light. So when I talk about a collapsible lifeboat, I mean, imagine just, you know, the easy example is Ikea. Think of your couch or your

entertainment unit or whatever that you put together and it weighed far more than you thought it could possibly weigh and it was so much more difficult to assemble than you thought it was even with that really helpful diagram that IKEA gives you and those nice little tools. A collapsible lifeboat was about nine meters long, about 27 feet.

And it was collapsible. It came down to a few inches, a few centimeters, 10 centimeters, something like that. But it weighed 1,000 pounds. It weighed 450 kilos. So while it's stored very conveniently, you still had to put it together and it was very difficult. So, you know, what we wanted to show was could you hide underneath the seats? If you were a Chinese passenger, could you hide underneath the seats comfortably?

of this collapsible lifeboat, which is what Ismay claimed. Ismay claimed that at daylight, these four Chinese men, as he put it, Chinamen or Filipinos, had hidden under the seats and that suddenly they emerged at daybreak and nobody knew where they came from. And we just thought that that was semi-ludicrous in a lifeboat that held 44 people. We just wanted to know what's possible. And the only way to do that was to build the boat and put real people in it and let physics tell the story.

Could you actually hide? Could you actually lie down in the bottom of this boat for four hours on a freezing night in April and not be kicked by other passengers, not be noticed by other passengers? Why was that? So I won't really give it away for people who may still read the book or...

But because nobody had tested it in over 100 years, the outcome was quite a surprise. The men did not act ignobly, I can tell you that. And it was much more of a physics problem than it was a problem of anyone trying to be devious, anyone trying to conceal themselves. That really was...

was not the issue. And again, I think this is where we can go with Titanic research in the future. Now we have the opportunity to create virtual twins of things. We can create models. We can do virtual reality walkthroughs of Titan.

Titanic, of its lifeboats, of the wreckage. You know, there's so much more that we can do with it. And, you know, that really gave us an opportunity here. And I can tell you that I got to play Ismay on the day. I didn't do the handlebar mustache or any of that good stuff. I wasn't in costume. But it was a genuine Eureka moment. And it was not...

not for the reasons that we thought. So it's, you know, you need to put these things to the test. You can't just let historical lies live on unchallenged because, you know, at the end of the day, we're talking about people's lives and we're talking about their dignity. And not everybody deserves a free pass from history. In our case, we never said that the Chinese men were heroes.

And we won't say that because that was not necessarily the case. But that doesn't also make them villains. You know, it's not a heads or tails situation where if you didn't step back from the rail and let somebody take your seat in the lifeboat, then you somehow were evil or that you somehow set out to claim someone else's seat. It's not like that. The survival logic, let's call it on Titanic, is very strange when you go back and look at it and who's pilloried afterwards and who gets a pass and so forth. It's not...

an ignoble act to want to survive. Everyone wants to survive. Don't believe otherwise, okay? It's wonderful that John Jacob Astor did what he did, stepping back, but I'm sure that he thought, especially at the very end as the water starts to come up around his ankles, is there a way?

could I do this? Can I get to a boat? I don't think he wanted to live any less than anyone else. So if we were able to do something to restore the reputation of these men who had been so badly libeled throughout history, then I would definitely say that that was one of the pluses of the project and its outcome. So Steve, I'm kind of thinking of going forward in terms of this story spreading worldwide. Do you think that it has legs

meaning to say certainly there should be and would be,

Great interest in this, not just because it deals with six Chinese survivors, but because it's just intrinsically a very interesting story. It has a lot to do with the Chinese diaspora during that time. What are your plans or hopes about this book or reviews of the book in mainland China? So the documentary got a full cinema release in 2021. It was supposed to be 2020, but because of COVID-19,

that didn't happen. You know, we were released in 10,000 cinemas in 2021. I mean, it's, I got to tell you, it's a strange experience to walk into a cinema and buy a ticket and watch yourself on a, you know,

you know, on a 10 meter screen. It's, it's weird. And it's, it was, it was so much fun, you know, in the beginning it was so daunting and just like, oh my God. And sadly, because it was still sort of end stages of COVID, I never got to eat popcorn and watch myself at the same time. So maybe when, when we do the sequel, the sixth,

the 6-2, the 12, and then I'll be able to do it then. But it was so funny because, you know, I'd go to these, like, weird... I promised myself that every day that I could possibly go, I was going to go.

Even if I was the only person in the theater, I just thought I got to support the cause. And when else am I going to be able to go to a cinema and see a movie that I am in? You know, I am not an actor. I don't have those aspirations. It was really funny. I walked in one day and I sat wherever I sat. And this giant group of school kids sat behind me. And this was not in Beijing. I was in Hunan province at the time. And

And I thought, well, I'm not really going to be able to slink out of here. So I just turned around and we had an impromptu Q&A. But I mean, the faces of, I mean, you know, imagine Han Solo turns around and greets you, you know, after. But, you know, I also had the opposite reaction, which was I sat behind a young couple in Beijing at like a 10 o'clock screening over by, I'm trying to think, you know, there's a cinema over by Yanshaw, like over near Kempinski in the, like the Four Seasons, that cinema.

So it was, I think it was the last time I saw it and I went in and I, I watched him, whatever this couples in front of me, they had their shopping bags, whatever. And the best moment was, you know, talk about humility. So these people have just watched this documentary that I've been in for a hundred minutes. It ends, they gather up their things. I'm the only other person in the theater. Okay. They, they take a quick glance at me. There's no recognition whatsoever. And they walked out.

And I waited until they got out of the theater and I doubled over in laughter. I mean, it was just the funny, it's like, keep working at it. But anyway, so we had a full cinematic release. And then the book came out, I think, in 2022 in the Chinese edition. Neither was a commercial success. It didn't gain that kind of traction. We certainly got a ton of media attention. I mean, there's definitely an awareness now.

and all kinds of Youku videos about people analyzing our footage and analyzing James Cameron's footage and talking about the story. It was definitely a critical success, which was nice. I kind of hope that there will still be someone who comes forward and says, "I think this is my grandfather. I think we might be related to this story." We had a couple of those people get in touch,

both sort of before and after, but nothing conclusive. You know, and I hope that some young researchers will decide that they can do better. I would not see that as a refutation, you know, they can take the boost from us. We took the, for the listeners who remember Leonard Nimoy's In Search Of show, we

suggested what possibly happened in many of the cases. We were not able to get six full stories. We got some of the stories, but not all the stories. But I think they're very representative of what was going on in the Chinese diaspora at the time. You have

People end up in the U.S., the U.K., maybe going back to China, maybe going back to Hong Kong. The story was definitely embraced by the Chinese media. I mean, to finally add a Chinese component to this beloved story, it's like I can't think of a good example of another story.

you know, another classic film where suddenly you, you, you know, add another dimension to it. I crossed my fingers ever so slightly when Titanic was re-released in 4k or, or whatever the, the, the,

the um anniversary release was when they re-released it in china i was really hoping that they would re-release it with the deleted scene of the chinese passenger being uh being rescued but it it didn't happen i don't blame cameron for for not not messing with it you know people want to have their experience and that's fine but um you know again i think stories have such a strange way of popping back up on their own i mean there was a there's a woman i think in the uk who

who's already written a young adult novel about it and with a female heroine and so forth. That's cool. It's great. We don't own the story. You know, we're not descendants ourselves, so we can claim the work that we did, but we can't claim that we own the story. And so, of course, other people are going to be interested in it. They're going to want to do their take on it. And I think that's pretty okay. I'd love to see somebody else advance the story as long as they do it

with the same kind of rigor and commitment to letting the facts speak for themselves. I think there's a lot of opportunity to muck with the story a bit and prettify it here and there.

And I would hate to see that. But, you know, there's been a lot of a lot more research recently about other passengers on the Titanic. By other, I mean not North American and not European. There's a there's a book called The Black Man on Titanic about a passenger from Haiti. There's been some work on the Middle Eastern passengers.

which is really just fascinating and quite different from anything else that's been done. So I hope that that's the way that we go forward with Titanic research. Ultimately, it's the human stories. That classic view that we've seen since 1985, it's 40 years now, almost 40 years exactly.

since the wreck was discovered. You know, it's great that we can scan it in 4K and 18K and eventually 16K, but the reality is that the wreck is going to continue to deteriorate. But it's the human stories that have always kept Titanic alive, and that's what's going to keep it going forward into the future. Well, Steve, you know, we really thank you for all of your hard work and your research, the detective work it took to bring these stories as best as you could to a reading and viewing public. The

The book is called the six, the untold story of the Titanic's Chinese survivors. It is out now. Also, Steve, if people want to watch the documentary as well, I know what's available on the streaming service Magellan. Is it available anywhere else for people to view it if they want to? So Magellan is, uh,

except for China. If you're in China, then try Youku or try Bilibili. In Chinese, it's Liuren. It's just like the English title. Or if you search for Liuren, Titanic Kehao, you'll find it for sure. You'll also find a bunch of other videos, but you'll find it for sure. It's also on Hive on Amazon Prime, which is spelled with an X. It's X-I-V-E. You need to establish a separate...

Hive account in order to watch it on Amazon Prime. It's not included with Prime per se. But between Magellan, Magellan spelled just like the Explorer, it's MagellanTV.com. Between one of those two, they both offer free trials. But if you use the free trial and at least register for an account, you'll be able to see it. There's a rumor of some new screenings coming up

in the United States, maybe even in Canada. So if you're desperate to see me as part of the live show along with the documentary, then stay tuned. There might be one in New Jersey later this summer, but we'll see. But it's available. People want to watch it. Thank you, Steve. And thank you, David, for joining us from Bangkok all the way from the other side of the world. My pleasure, as always. When are you back in Beijing?

On the 10th of May. Nice. All right. Well, I'll talk to you then. And thank you all for listening. This has been an episode of Barbarians at the Gate. You can always find us wherever fine podcasts are given away for free. And I hear the sound from beyond the ridgeline, the drums.