Deep Dive

Why did the DC Circuit uphold the TikTok ban despite First Amendment protections?

The DC Circuit upheld the TikTok ban by emphasizing national security as a compelling government interest. The court argued that the law was narrowly tailored to address foreign adversary control over TikTok, and there were no less restrictive alternatives. The decision also deferred to the government's expertise in national security matters, making it difficult for TikTok to challenge the ban on First Amendment grounds.

What was TikTok's proposed remedy to address U.S. government concerns?

TikTok proposed 'Project Texas,' which involved physically storing all U.S. user data in Oracle's U.S.-based database and allowing Oracle to audit the data and source code. Additionally, the U.S. government could temporarily shut down TikTok if necessary. However, this remedy failed because TikTok's global operations meant data could still be shared with ByteDance, making complete data isolation impossible.

How does the PAFACA law differ from the RESTRICT Act in targeting TikTok?

PAFACA directly targets TikTok by listing it in the law's text, while the RESTRICT Act broadly addresses foreign adversary-controlled entities. PAFACA shifts enforcement to third-party service providers like Google and Apple, making it self-enforcing. In contrast, the RESTRICT Act requires the government to individually review and prohibit transactions, giving it more discretion but also more responsibility.

What role does national security play in the TikTok ban decision?

National security is the central justification for the TikTok ban. The court ruled that the government has a compelling interest in preventing foreign adversaries from controlling platforms that could manipulate U.S. public opinion. The decision deferred to the government's assessment of national security risks, making it difficult for TikTok to argue against the ban.

What are the implications of the TikTok ban for other foreign-owned platforms?

The TikTok ban sets a precedent for regulating foreign-owned platforms, particularly those perceived as national security risks. While the law specifically targets TikTok, its framework could be applied to other platforms like WeChat. However, the court's decision emphasized that the ban was narrowly tailored to TikTok, leaving room for future cases to be judged on their own merits.

How does the TikTok ban reflect broader trends in U.S. policy toward foreign influence?

The TikTok ban reflects a growing emphasis on national security over economic and free speech considerations in U.S. policy. It highlights a shift toward stricter regulation of foreign-owned entities, particularly those from adversarial nations like China. This trend aligns with broader geopolitical tensions and a focus on protecting U.S. interests from foreign interference.

What are the potential consequences if the Supreme Court takes up the TikTok case?

If the Supreme Court takes the TikTok case, it could either uphold the ban, reinforcing national security as a priority over free speech, or reverse it, potentially weakening the government's ability to regulate foreign-owned platforms. However, reversing the decision would be challenging given the strong legal and political consensus supporting the ban.

How does the TikTok ban compare to similar actions in other countries?

The TikTok ban is part of a global trend where countries are increasingly regulating foreign-owned platforms, often citing national security concerns. For example, Australia has banned social media for teenagers, and Brazil has banned platforms like X (formerly Twitter) for failing to comply with local laws. These actions reflect a broader shift toward prioritizing national security and sovereignty over global digital openness.

- 美国法院驳回TikTok对PAFACA法案的核心质疑,包括第一修正案。

- 法院认为政府的措施符合国家安全利益,且具有针对性。

- TikTok的诉讼策略未能成功挑战法案。

Shownotes Transcript

Call it tiktok ban, PAFACA, 啪发卡;it’s been upheld and we try to make sense of it. Too long don’t listen version: 言论自由天下第一,但国家安全是天。

(1:27) some (not much) context

(6:34) How can 啪发卡 be so well drafted in such a bad way? 群众互斗,名列前茅,卡点巧思,与忒修斯之船

(17:11) What was the F word that screwed tt 3 times in the decision? 言论价值倒反天罡,tt的诉讼不可能两全策略,与帝国落日的边疆

(44:12) What implications ensue? 压力来到了SCOTUS,川普,和马斯克这边(吗?)

(1:01:26) 彩蛋;or, any freedom thereof notwithstanding, how not everyone can give a nice speech.

本期(事实上,任何一期)播客不构成法律建议或雇主意见而只是sound and fury told by two podcasters signifying nuthin'. This is not even a 法律播客,but a parody of a 法律播客,ffs.

Some references:

TikTok v. Garland (D.C. Cir. 2024)

“Restricting the Emergence of Security Threats that Risk Information and Communications Technology Act” or the “RESTRICT Act”, S.686) (118th Congress 2023-24)

“Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act” or 啪发卡,H.R.7521) (118th Congress 2023-24), as a part of H.R.815

Ashcroft v. ACLU (SCOTUS 2004) (filters are a qualified alternative to criminal penalty/fines of for distributing minor-harmful content) (3:43)

Murthy v. MO (2024) (users lack Article III standing to seek injunction of gov’t from pressuring social media platforms to censor speech) (8:58)

Moody v. NetChoice (SCOTUS 2024) (”Corporations, which are composed of human beings with First Amendment rights, possess First Amendment rights themselves. But foreign persons and corporations located abroad do not. So a social-media platform’s foreign ownership and control over its content-moderation decisions might affect whether laws overriding those decisions trigger First Amendment scrutiny.") (14:57)

Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar (SCOTUS 2015) (18:16)

Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (SCOTUS 2010), and Breyer’s dissent (18:32) [was actually only cited 11 instead of 100 times here, majority & concurrence combined]

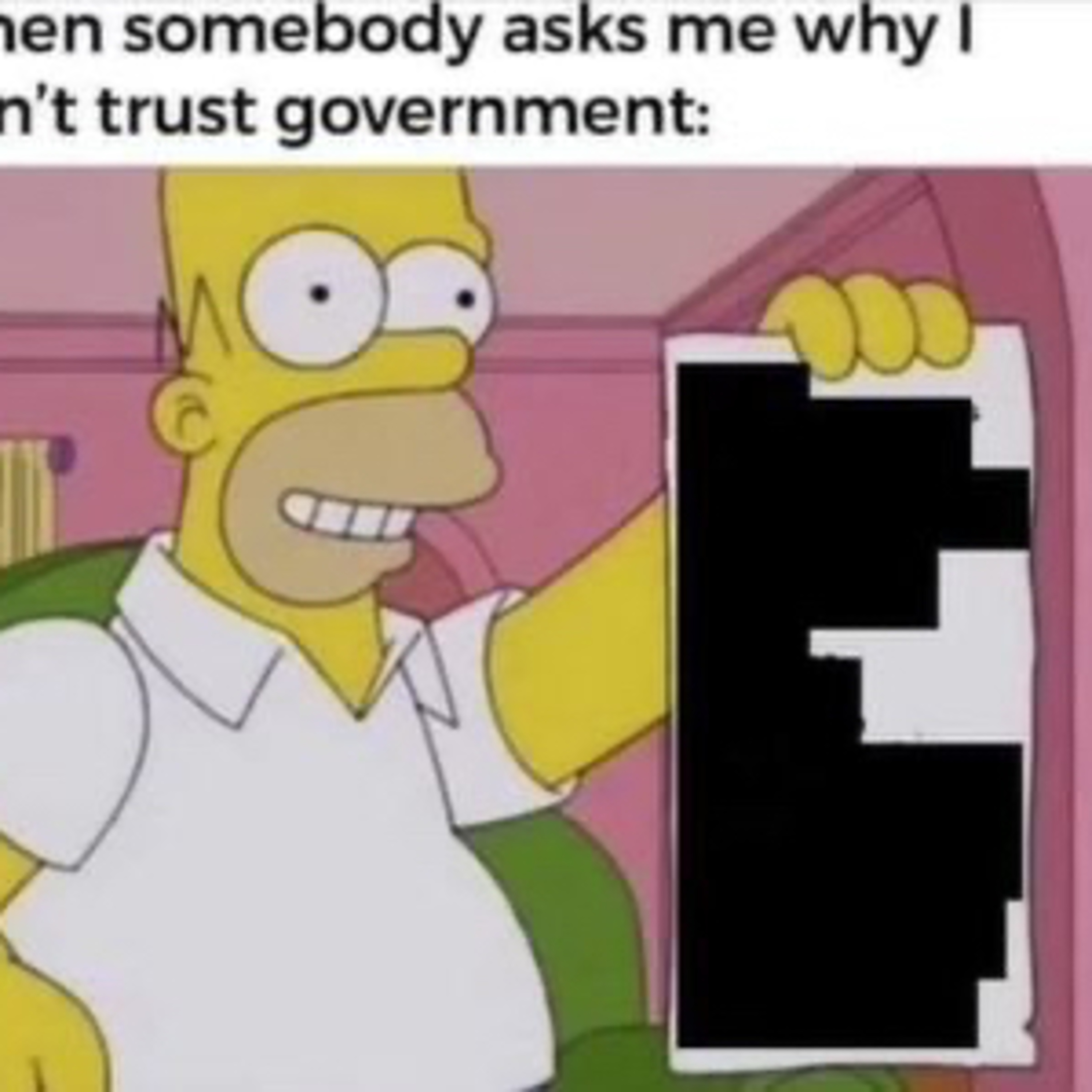

Gov’s redacted brief (or the lack thereof)) (21:38)

Lamont v. Postmaster General (SCOTUS 1965) (29:58)

“The Constitution is not a suicide pact.” Terminiello v. Chicago (Jackson’s dissent, 1949) (36:59)

Australia banning stuff) (53:50); Brazil banning and unbanning stuff) (56:26)

Brown v. Entertainment merchants Ass'n (SCOTUS 2011) (54:50)

NY v. Ferber (SCOTUS 1982) (55:13)

Murdoch seeking citizenship (59:37); FCC v. Pacifica Foundation (SCOTUS 1978) (1:00:07)

附加思考题:

- What about overbreadth doctrine? What about vagueness doctrine? And why did Tiktok not argue them?

- How was the FCC-Murdoch regulation constitutional?

bgm credit to suno ai