Deep Dive

- Autogyros are a type of flying craft that combines features of airplanes and helicopters.

- They have a rotor on top but it's unpowered, rotating due to air flowing over it.

- Unlike helicopters, they use a propeller for thrust, usually mounted behind the cockpit.

Shownotes Transcript

We're all familiar with things that fly in the air. Hot air balloons, dirigibles, blimps, airplanes, and helicopters. However, there's another category of flying craft that most people aren't familiar with. It isn't an airplane, and it isn't a helicopter. It actually lies somewhere in between. By combining parts of both, it has some amazing properties that neither one has. Learn more about the autogyro, what it is, and how it works, on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily.

This episode is sponsored by Quince. It's summertime, and that means it's time to bring out the summer clothes. If you're looking to update your wardrobe this summer, I suggest you check out Quince. Quince has all the things you actually want to wear this summer, like organic cotton silk polos, European linen beach shorts, and comfortable pants that work for everything from hanging out in the backyard to nice dinners.

And the best part? Everything with Quince is half the cost of similar brands. By working directly with top artisans and cutting out the middleman, Quince gives you luxury pieces without the markups. I recently needed a new duvet, and I went to Quince and picked up a great one that looked much better than what I had before, and all at a fraction of the price I'd pay elsewhere.

Stick to the staples that last with elevated essentials from Quince. Go to quince.com slash daily for free shipping on your order and 365-day returns. That's q-u-i-n-c-e dot com slash daily to get free shipping and 365-day returns. quince.com slash daily. This episode is sponsored by Mint Mobile.

Do you know what doesn't belong in your summer plans? Getting burned by your old wireless bill. While you're planning beach trips, barbecues, and three-day weekends, your wireless bill should be the last thing holding you back. And that's why I use Mint Mobile. With plans starting at $15 a month, Mint Mobile gives you premium wireless service on the nation's largest 5G network.

The coverage and speeds you're used to, but just less money. So while your friends are sweating over data usages and surprise charges, you'll be chilling literally and financially. With Mint Mobile, you can use your same phone, same phone number, and contact list, and even connect to the exact same towers and cellular networks. The only difference is the price.

This year, skip breaking a sweat and breaking the bank. Get your summer savings and shop premium wireless plans at mintmobile.com. That's mintmobile.com. Up from paying $45 for a three-month 5GB plan required, equivalent to $15 a month. New customer offer for first three months only, then full-price plan options available. Taxes and fees extra. See Mint Mobile for details. I have a lot of odd fixations, and one of those I've had for years is the auto gyro.

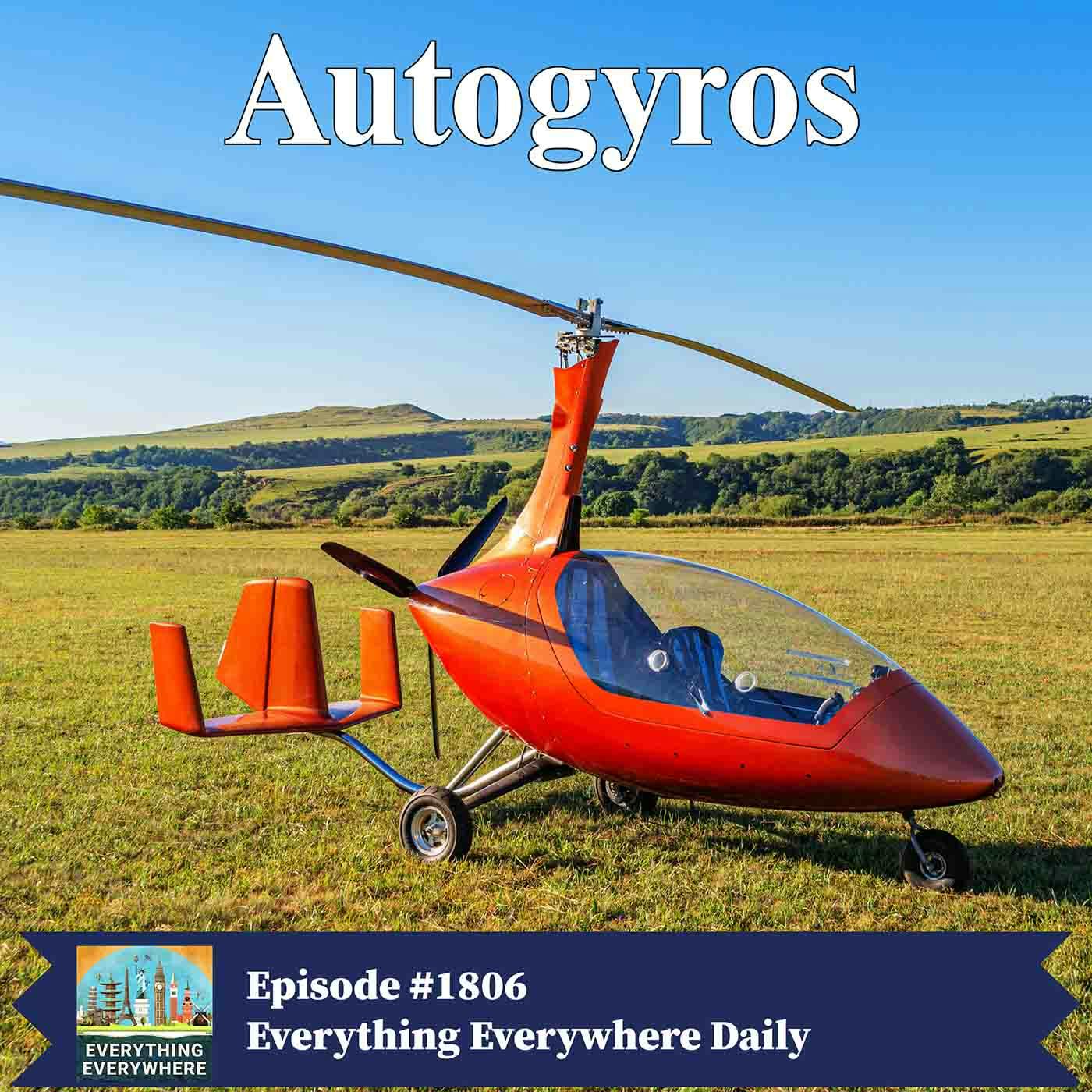

I'm not an auto gyro pilot, and to be honest, I've never even flown in one, but I am fascinated with them. For the record, the auto gyro is sometimes called a gyroplane or a gyrocopter, but they're all pretty much the same thing. If you don't know what an auto gyro is, if you've never seen one before and you look at one for the very first time, your first instinct would be to say that it's a helicopter because it has a rotor on top just like a helicopter.

However, it is not a helicopter, and it differs from a helicopter in a few important ways. The biggest is that the rotor in an autogyro isn't powered. It rotates like a pinwheel due to air flowing over it. But like a helicopter, the rotor is what provides the lift for the aircraft. Because the rotor isn't powered, it doesn't need a tail fan like a helicopter does to counteract the torque produced by the main rotor.

Because the rotor isn't powered, it can't be used for thrust like a helicopter. Instead, it has a propeller like an airplane does, and they're usually mounted behind the cockpit instead of the front. So why was this Frankenstein flying contraption invented, and what purpose does it serve exactly? The history of the autogyro begins in the early 20th century with the pioneering efforts of Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva.

In the aftermath of World War I, Sierra was deeply concerned by the number of aviation accidents caused by aerodynamic stalls. In those days, when an airplane's speed dropped too low, it would lose lift suddenly and catastrophically, often resulting in fatal crashes. His breakthrough came from observing how maple seeds spiraled gently to the ground, their wing-like structures auto-rotating as they fell.

Cerva realized that if he could harness this principle of autorotation, he might create an aircraft that could descend safely even if its engine failed. The concept was elegant in its simplicity. As the aircraft moved forward, air would flow upward through the rotor disc, causing the blades to spin and generate lift continuously regardless of engine power.

Sierra's first successful autogyro, the C4, took to the air on January 17, 1923 at Jatafé Airdrome near Madrid. The machine looked peculiar by the standards of the day, with its large rotor mounted above a conventional fuselage and the propeller at the front for forward thrust. The rotor itself was a marvel of engineering innovation. Sierra had solved the fundamental problem of "dissymmetry of lift."

The fact that in forward flight, the advancing blade generates more lift than the retreating blade by incorporating hinged blades that could flap up and down to equalize the lift distribution across the rotor disc. The success of the C-4 marked the beginning of rapid development. Sierra established the Sierra AutoGyro Company and began licensing its technology internationally. The key to understanding the AutoGyro's appeal lies in recognizing the state of aviation in the 1920s and 30s.

Airports were few and often unpaved, aircraft engines were unreliable, and pilots were still learning how to handle the tricky flight characteristics of early airplanes. The autogyro promised to address many of these concerns with its ability to take off and land in very short distances, its inherent safety in engine-out situations, and its relatively forgiving flight characteristics. By the late 1920s, autogyros were being manufactured under license in several countries.

In Britain, the De Havilland Corporation and later Avro produced Sierra Auto Gyros, while in the United States, Pitcairn Aircraft Company became the primary manufacturer. Harold Pitcairn, an aviation enthusiast and businessman, recognized the potential of Sierra's invention and acquired the manufacturing rights for North America. The Pitcairn Auto Gyros, particularly the PCA-2 and later models, became synonymous with American auto gyro development.

The 1930s represented the golden age of the autogyro. These aircraft found applications in various roles that highlighted their unique capabilities. Mail delivery services adopted autogyros for routes between small towns where conventional aircraft couldn't operate efficiently. Police departments experimented with them for traffic patrol and surveillance, taking advantage of their ability to fly slowly in land and confined spaces. The military showed considerable interest, seeing potential for observation, liaison, and even combat roles.

The autogyro also captured the public's imagination in ways that went far beyond its practical applications. These machines appeared in newsreels, were featured in air shows, and became symbols of the exciting possibilities of aviation. Amelia Earhart famously flew a Pitcairn autogyro, setting several records and helping to promote the type. The distinctive appearance of an autogyro with its freely spinning rotor and conventional propeller made it instantly recognizable and added to its mystique.

However, even as autogyros reached the peak of their development and public attention, the seeds of their decline were already being sown. The late 1930s saw rapid improvements in conventional aircraft design. Engines became more reliable, reducing the safety advantage of autorotation. Airport infrastructure improved, making the autogyro's short field capabilities less critical. And most significantly, the helicopter began to emerge as a practical aircraft.

Igor Sikorsky's successful helicopter flights in 1939 and 40 demonstrated that vertical takeoff and landing were achievable with powered rotors. While early helicopters were more complex and expensive than autogyros, they offered capabilities that autogyros simply couldn't match: true vertical flight, hovering, and backwards flight. The helicopter could do everything an autogyro could do, plus much more.

World War II effectively ended the era of autogyro development. While some military applications continued, resources were redirected towards more conventional aircraft and the emerging helicopter technology. By the war's end, major autogyro manufacturers had either closed their operations or shifted to other types of aircraft production.

The post-war period saw autogyros enter what might be called their wilderness years. Commercial production had largely ceased, and the few autogyros that remained in service were gradually retired or regulated to museums. However, the fundamental principles that made autogyros attractive – simplicity, safety, and short field performance – never disappeared entirely.

The Ferry Rotodyne was a British experimental compound gyroplane developed in the 1950s by Ferry Aviation as an ambitious attempt to combine the vertical takeoff and landing capabilities of a helicopter with the speed and efficiency of a fixed-wing aircraft. Designed for short-haul passenger and cargo transport, the Rotodyne featured a large, unpowered main rotor for auto-rotative lift during cruise flight,

but used jet tips, aka small nozzles in the ends of the rotor blades fueled by compressed air and gas, to spin the rotor for vertical takeoff and landing. Once airborne, the rotor auto-rotated while a pair of wing-mounted turboprop engines provided forward thrust. The engine performed well in tests, setting a speed record for rotorcraft of its type and demonstrating potential as a city-center airliner.

but it was ultimately cancelled in 1962 to a combination of political shifts, noise concerns from the tip jets, and a lack of commercial orders. The revival began in the 1960s and 70s, coinciding with the development of ultralight aircraft and the growth of the home-built aircraft movement. Enthusiasts rediscovered the Autogyro's appealing characteristics and began developing new designs specifically for amateur construction.

Wing Commander Ken Wallace was a pioneering British aviator and engineer who played a crucial role in the development and popularization of modern gyrocopters in the post-World War II era. A former RAF pilot and accomplished aircraft designer, Wallace built and flew numerous autogyros of his own design, most notably the Wallace WA-116, which gained international fame when he flew it as James Bond's gyrocopter Little Nelly in the 1967 film You Only Live Twice.

Wallace also advanced gyrocopter technology through innovations in stability, control, and performance, and he used his aircraft in various roles including police surveillance, agricultural monitoring, and experimental research. He also set multiple world records for speed and altitude in gyrocopters, helping to demonstrate their potential beyond recreational aviation. So, why would anyone want to own an auto gyro today? What role does it fill in a world with advanced avionics?

Well, for starters, auto gyros have short takeoff and landing capabilities. Gyrocopters require very little runway to take off and can land in extremely short distances, sometimes in less than 10 meters or 30 feet, making them ideal for operations in confined or remote areas without prepared runways. While normally not capable of true vertical takeoff like helicopters, their short takeoff and landing performance is superior to that of most fixed-wing aircraft.

That being said, some autogyros do vertical takeoffs. And they do it by temporarily providing power to the rotor for a few seconds to get it off the ground before letting it spin freely when it starts moving forward. And this isn't so much of a vertical takeoff as it's a jump takeoff, which is what I've seen it called. The second major benefit is, of course, that autogyros are safer in engine-out scenarios, which is why they were invented in the first place.

One of the most significant safety advantages of an autogyro is its ability to auto-rotate. So, even if the engine fails, the unpowered rotor continues to spin, allowing the aircraft to glide down gently and land safely. This makes engine failure less catastrophic compared to airplanes, which need speed and altitude to glide, or helicopters, which require quick pilot reactions to enter auto-rotation. The third is that autogyros have a lower cost of ownership and operation.

Gyrocopters are generally cheaper to buy, maintain, and operate than helicopters or fixed-wing planes. They have fewer moving parts, especially compared to helicopters, which have complex rotor head mechanics and transmission systems, resulting in less frequent and less expensive maintenance. For a personal aircraft, the cost differences between autogyros, planes, and helicopters can be dramatic.

While there are enormous differences in prices, so kind of take this with a pinch of salt, a new auto gyro can be anywhere from half the price to one-tenth the price of a new two-seater plane or helicopter. Finally, in many countries, the training time required to earn a gyrocopter license is shorter and less expensive than that for helicopters or fixed-wing aircraft. The relative simplicity of operation makes them accessible to amateur aviators.

So then, what's the downside? Well, for starters, they can't fly as fast as either helicopters or airplanes. The fastest recorded speed for an autogyro is approximately 207 mph or 334 kmph. The fastest helicopter speed officially recognized is 293 mph or 472 kmph. Even propeller-driven planes have been able to get somewhat close to the speed of sound.

By the same token, autogyros can't fly as high. The record is only 8,400 meters or 27,500 feet. Several companies are currently considering the use of autogyros for urban air taxis. So far, these initiatives are still in the planning stages and no launches have been made yet. There are, however, several companies producing autogyros for the personal aircraft market.

The autogyro fills a unique space in the aviation market. They might be slower and fly lower than other types of aircraft, but they're also safer, cheaper, and easier to fly. Maybe if someone can figure it out, you might take an autogyro on a short urban flight sometime in the near future. The executive producer of Everything Everywhere Daily is Charles Daniel. The associate producers are Austin Oakton and Cameron Kiefer.

I want to thank everyone who supports the show over on Patreon. Your support helps make this podcast possible. I'd also like to thank all the members of the Everything Everywhere community who are active on the Facebook group and the Discord server. If you'd like to join in the discussion, there are links to both in the show notes. And as always, if you leave a review or send me a boostagram, you too can have it read on the show.