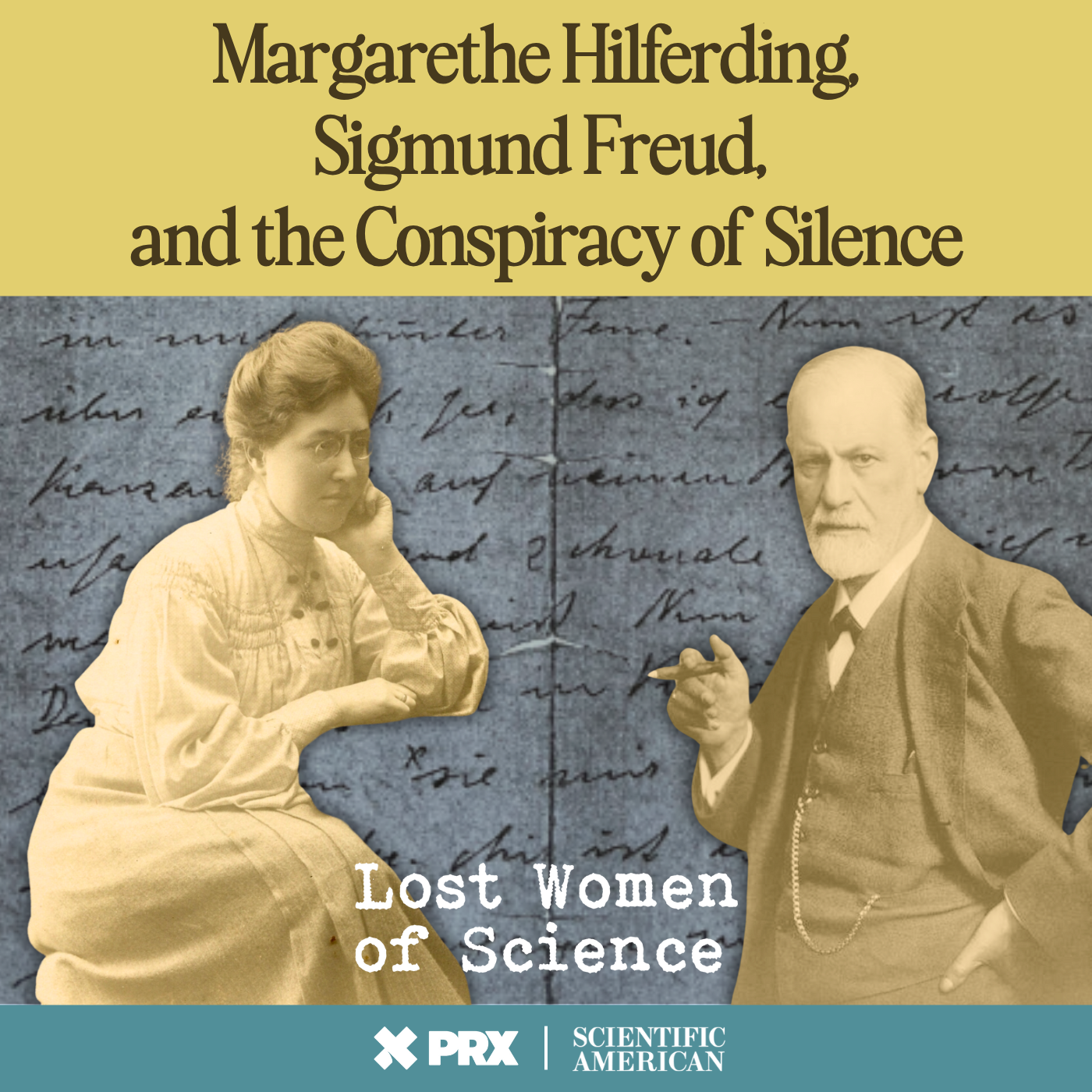

Margarethe Hilferding, Sigmund Freud, and the Conspiracy of Silence

Lost Women of Science

Deep Dive

- Margarethe Hilferding was the first woman to earn a medical degree at the University of Vienna and the first woman to join Sigmund Freud's Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

- Her groundbreaking work on maternal instinct challenged established norms and remains relevant today.

- Hilferding's story, like many brilliant women's, was largely overlooked until recently, thanks to the work of historians and psychoanalysts.

Shownotes Transcript

This episode is brought to you by Progressive Insurance. Fiscally responsible, financial geniuses, monetary magicians. These are things people say about drivers who switch their car insurance to Progressive and save hundreds. Visit Progressive.com to see if you could save. Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. Potential savings will vary. Not available in all states or situations. The year was 1945. World War II had just ended in Europe.

and a soldier named Peter Milford headed back to his home in Vienna. He fought in the army to free Austria. He came back to find out what remained of his beloved city and the mother he had left behind. Everything had been destroyed. In the rubble, he was looking for the surviving friends. When he left Vienna before the war, his name wasn't Peter Milford.

It was Peter Hilferding. He'd changed his name in New Zealand, where he'd escaped as a refugee. Before the war, in this very building, Peter's mother published articles about hunger, housing, and the rights of the working class on behalf of the Social Democratic Party.

A trained physician, the first woman to graduate from the University of Vienna Medical School, she worked tirelessly on behalf of women's health and reproductive rights. She was the first woman to be accepted into Sigmund Freud's Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. He opened the door late at night and told who he was, and they took him in and gave him a bed for a night. His mother's name was Margarita Hilferding, or Margaret in the English pronunciation.

And her contribution to the field of psychoanalysis was so prescient, so forward-thinking, that it remains radical to this day. She would challenge the deeply ingrained notion that a mother's love for her child is innate.

Then he walked to the outskirts of Vienna to the place of his aunt. And his cousin, her father, gave him a suitcase that Margarethe Hilferding had left for him. What Peter had left Vienna to escape was the same crushing reality that his mother could not. The Hilferdings were Jewish, which in wartime Vienna was a death sentence.

in the awful place where she had been gathered with other Jews and some old clothes, and that was all. And they gave him her letter of goodbye. I'm Marcy Thompson. Today on Lost Women of Science, we examine the fragments of the remarkable life of Margaret Hilferding.

As is so often the case with brilliant women, her story might have gone unnoticed. At best, a footnote on the pages of someone else's story. At worst, another tragic victim of the Holocaust. But as we'll see, Hilferding left behind much more than that, starting with that suitcase.

and what was uncovered by the indomitable curiosity of a few women, a handful of historians and psychoanalysts who examined the origins of Sigmund Freud's groundbreaking work and discovered, to their surprise, the female medical doctor who was there at the beginning. My name is Eveline List. I studied psychology.

First history in psychology, and after my doctorate, I decided to start psychoanalytic training to understand something about people. I wanted to understand how things and people were connected. It sounds a little bit like why Hilding herself went in to study the same thing. Exactly. I mean, yeah. What drew you to her?

Where did you discover her? I spoke to a friend who was the head of the documentary archives of the resistance movements in Vienna. And then he said, well, aren't you interested in some materials? And I said, well, yeah, what you got? And so he suggested Margarita Hilferding. I've always been very much into the history of psychoanalysis.

So I knew she had been the first one. Of course, I was very interested. They had very little about her. But what she gave me was the starting point. Evelina List would soon connect with Hilferding's son, Peter Milford, the same person who had returned to Vienna so many years earlier. Turns out they lived fairly close to each other.

When Evelina met Peter, he was well into his 90s. He was intellectually very bright and open, and he also had a very dry humor. But at the same time, he was very humble. Peter Milford provided Evelina with a firsthand account of his mother's astonishing accomplishments. He traced her story back before the turn of the 20th century, when enormous cultural change was taking place.

In the late 19th century, Margaret Hilferding was part of an unusual historical phenomenon. She was among a growing group of highly educated, liberal Jewish women who studied medicine in Europe. A subset of these women were drawn to the nascent field of psychoanalysis. Outside of academia, these women are unknown. And even within academia, these pioneers have received little attention. We, of course, know that that's

the tendency to cut out from official history, to cut out the minorities, and that includes women. That's Klara Nashkowska, cultural historian, professor of women's studies at Montclair State University, and editor of the book Early Women Psychoanalysts. Nashkowska's research focuses on a somewhat better-known Russian physician, who was also a pioneer in the field, Sabina Shpilorain. As I was researching Shpilorain, I was discovering more and more names.

I mean, I wasn't definitely the first one to discover this, but I discovered for myself that there were so many of those women. Almost all of those women were also Jewish, which was also another factor leading to their disappearance from history. And that while each of them had an individual story, there were so many also common threads in those stories when it comes to gender, Jewishness, antisemitism.

By the late 1800s, a cultural shift was taking place among progressive Jewish families in Europe and Russia. Especially those who subscribed to Marxist ideologies. They began educating their daughters. We have a very typical family there. And that's a Jewish family where parents are Jewish.

Either observant or maybe observe some of the holidays. Those parents typically, especially fathers, support their daughters in pursuing university level education, in becoming doctors, in becoming psychoanalysts and generally speaking, financially independent professionals.

and not marrying. While this describes the characteristics of Margaret Hilferding's family to a T, it doesn't necessarily explain why Hilferding herself would eventually be drawn to this new field, or what made her into the formidable figure she would become. For that, we need to understand the depth and breadth of her intellect, and her overriding desire to work on behalf of women.

She contributed so significantly to several fields, the field of medicine, the field of psychoanalysis.

She really advocated for rights to contraception and abortion. This is the early 1900s. Candice Dumas is a clinical psychologist with a practice in Cape Town, South Africa. She was also interested in tracing the first generation of women in psychoanalysis. But while Dumas was aware of pioneers like Sabine Spielrein, she knew nothing of Margaret Hilferding, even though she was part of the headwaters of psychoanalysis itself.

And I think she paved the way for other women to join the fold and be accepted as well at the end of the day. As is the case with so many lost women scientists, Hilferding was undeniably brilliant, excelling well beyond what was expected of her.

or even her male contemporaries at the time. She knew from the very beginning she wanted to study medicine, and she was willing to jump through all the right hoops to get there. To put these hoops in perspective, in 1897, Margaret was one of three female students who were enrolled to study for an academic degree at the university. That's out of 15 million women who lived in Austria-Hungary at the time. She enrolled to study physics and math, but could

only do so if professors allowed women in their classes. Here's Evelina List. They were made fun of and professors were, some of the professors were really neglecting simply that they existed or, you know, didn't let them to their lectures.

The argument of the majority who was against women studying was so far-fetched and ridiculous. You know, like, there are so many bald men and that's a sign of how their brain is functioning. And when women would start studying, they'd lose their hair and their fertility. Despite these ridiculous attitudes, Margaret continued to pursue her goal. Here's Candice Dumas.

She started taking medical courses on the side as kind of an underground student until finally that women were allowed to officially study medicine. And actually, the opening of the medical university happened not because they suddenly got all so enlightened, but that they desperately needed female doctors because in Bosnia, which Austria had occupied,

the women refused to go to male doctors. And so they needed female doctors. And in 1903, at age 32, Margaret Hilferding became the first Austrian woman to receive her medical degree from the University of Vienna after completing her entire formal education there. Things were beginning to change. And although anti-Semitism and misogyny were still alive and well in Austria, the era of progressive Viennese modernism was underway.

It was a time of radical social change. There were several emancipatory movements at that time. Austria had been ruled for centuries by the conservative Habsburg dynasty and was solidly Catholic. But more progressive thinking was taking hold. The largest, of course, was the labor movement.

There was the women's movement. There were all kinds of health movements. And in the coffeehouse culture that the era is famous for, Margaret found her way to a group of radical intellectuals who reflected her own desire for progress, the Socialist Students League.

They met in one cafe regularly, starting to read the Neue Zeit, which was the social democratic periodical from Germany. They were reading Karl Marx and discussed among each other. Margaret was the group's first female member, and it was there that she met her husband, Rudolf Hilferding, who was seven years her junior.

He was also a medical doctor, and like Margaret, he was interested in a multitude of subjects. Candice Dumas explains the union. It was really an intellectual marriage and a marriage of equals. They were both raised Jewish, and they decided on a civil marriage instead of a religious ceremony. Margaret worked at the Vienna General Hospital, fighting to be called Frau Doktor, not simply Fraulein.

and Rudolph's interest expanded into the field of economics and the need for political reform. Both of them felt frustrated that their medical training didn't prepare them to understand the psychic and social conditions that impacted their patients' lives. Rudolph moved away from medicine and veered fully into politics.

The couple moved to Berlin, where Rudolf was invited to lecture for the German Social Democratic Party. They had two children, Karl and Peter, and Rudolf threw himself into writing what would become a groundbreaking and career-making Marxist treatise called "Finance Capital." His career seemed boundless, but Margaret

found herself alone, raising two children and unable to practice as a doctor in Germany. Without a degree from a state-controlled university, it was impossible for her to put her vast education and drive to work. So much for all that Marxist talk of emancipation.

Here's Evelina List. Here they were talking about all those enlightened ideas and revolutionary perspectives. And then he actually expected her to do all the work by himself, but he followed his interests. All that she had worked for was suddenly impossible. Margaret was faced with a choice.

He wanted to stay, and she needed to go back to where she was free. She packed up two very young children and moved back and looked after them on her own. She loved raising her children, but she also loved her work. Rudolph stayed in Germany. He eventually became the minister of finance for two social democratic-led governments. But their marriage was over. Margaret returned to Vienna with her children and set up a medical practice treating women in a working-class district. ♪

Margaret's patients had most likely never been to a female doctor. As their physician, she functioned as a gynecologist, but also as a counselor. She saw the impact of their social conditions. She witnessed their suffering. She listened.

Here's Candice Dumas. She went into the depths of their psyches and we could explore with them. She saw how overburdened women were and how it impacted them economically. It impacted them physically.

Her medical training, however, wouldn't have included any way of understanding how these factors contributed to her patients' health. And she wouldn't have had an empirical approach to alleviating their mental suffering. Universities were still years away from offering any kind of psychological training. It just didn't exist. But the new field of psychoanalysis, which had started in Vienna a few years before and was just taking root,

offered both a framework for understanding internal psychological struggle and also a way of placing patients in a broader social context. Both were part of Margaret's personal mission. Klara Nashkowska explains that psychoanalysis would have offered Margaret some insight, especially in light of the political turmoil of the time. In Europe, it was a very broad cultural project.

It was a sociopolitical project. It was a way of looking at people. So it included a lot of different factors, and therapy was one of them. The pioneering work of Sigmund Freud framed this internal unrest in a new way. Here's Candice Dumont. Freud was looking for connections. What's going on underneath? What is driving people's behaviors and emotions and feelings?

difficulties that they get stuck with. So this is also the realm is that it's not only about getting patients to talk and focusing on what is spoken, but in looking at what is underneath that and what is potentially unspoken. Margaret would certainly have been familiar with Freud's lectures in Vienna, as well as his written work. His theories were a topic of discussion, especially among the followers of progressive movements. Evelina List believes there was a

clear reason that Margaret was drawn to Freud. There was the idea of being able to understand her patients better.

Margaret Hilferding and Sigmund Freud had many acquaintances in common, and soon enough she made her way to Freud himself. It's almost as though it was meant to be that they were going to cross paths. The all-male Vienna Psychoanalytic Society originally met at Freud's apartment on Wednesday evenings. But in that cozy enclave where the subconscious lives of men and women would be plumbed, there was some doubt that a woman doctor would have anything of value to contribute.

So we know there was a huge debate about whether women actually have that cognitive capacity to become doctors and psychoanalysts. And it's not pretty, let's say. There were really outrageous things happening.

were said. That's Rosemary Balsam. Particularly by one of my nemesis, Fritz Sittles. And he said that, well, as medical students, they're harmless women because any normal kind of essentially red-blooded man in medical school treats them as prostitutes. But one

Once they're graduated, they're a real threat. Nobody should give power to a woman because they'll abuse their power. Rosemary Balsam is a fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists of London and an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the Yale Medical School. So this was kind of, you know, an attitude that was shared by a lot of them. Freud himself sort of viewed Bittles as, you know, boys will be boys and so on.

Even though Freud had stated that, quote, women cannot measure up to men in their capacity of sublimation of sexuality, unquote, he was well aware of the progressive thinking in the cultural circles surrounding the group, and he called for the intellectual openness to accept women as members.

In 1910, 38-year-old Margaret, a physician with the highest education it was possible for anyone to achieve, a deep political commitment, and mother to two young boys, was taken into consideration as the group's first female member.

They vote and the vote is in favor of accepting her. But this is kind of like the beginning. It was a historical moment. Although there had been one example of a woman attending a meeting, it was an altogether different accomplishment to be accepted as a member.

Margaret had taken down that barrier as another first. Evelina List. I think she impressed them enormously. Within a year, she presented her own research. It was a paper called On the Basis of Mother Love. It was a thesis that grew directly out of Margaret's practice as a physician. It would determine her relationship to the field of psychoanalysis, and it would cause some very big waves among Freud and his esteemed male colleagues.

More after the break.

Marguerite Hilferding basically created the field of psychoanalysis that Freud and Jung credited in their papers, yet no one's heard of her. Dr. Charlotte Friend discovered the Friend's leukemia virus, proving that viruses could be the cause of some types of cancers. Yvette Cochoir discovered the element astatine and should have won the Nobel Prize for that.

Margaret had been a member of Freud's Vienna Psychoanalytic Society for less than a year when she presented her revolutionary paper to the group. It

It was called On the Basis of Mother Love. It should be noted that the actual paper no longer exists. The minutes of the meeting, which were recorded by Otto Ronk on January 11, 1911, are essentially a summary of Hilferding's presentation. But Rosemary Balsam believes Otto Ronk most likely represented the paper accurately. One of the things that I appreciated very much about Ronk's

minutes. It's more open than any kind of notes I'm sure we would write these days, much more open and much more descriptive. And so it really does convey her thinking. And Hilferding's thinking proved to be extraordinary. Clara Nashkowska explains. So this paper and this presentation she gave, Motherly Love, was incredibly ahead of her time.

in just a mind-blowing way. The central thesis of Margaret's paper was hard for the men in the room to comprehend. She said there is no maternal instinct. No maternal instinct.

Even today, that is a bold assertion. Margaret put forth the idea that there is no innate maternal love, as she called it. I mean, it's still incredibly progressive because she talked about things that we're still dealing with, such as this idea of maternal instinct. This idea that if you don't have it, then you're a bad parent, you're a bad mother.

The research that Margaret conducted for this paper was rooted in the lives of real women. It came directly from her experiences as a physician and as a mother herself.

As an extremely rare example of a female physician who treated women, she had unparalleled insight into her patients' lives. Candice Dumas. She could explore with her patients, I think, in a way that male doctors at the time couldn't, whether these women actually wanted to be mothers or not. And that was radical thinking for both women and men at that time.

This idea went against the grain of how women had been perceived historically, culturally, and biologically. It goes against that same grain today. We are meant to think of ourselves as natural caretakers who immediately bond with our children as a matter of species survival.

That's how we are taught that women are wired. And that was precisely the thinking of the men in the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. And I think that it was the kind of Darwinian biological kind of sense that derived from what they all knew from animal life. They were all very taken with how female animals would protect their young and so on. And it was felt that

that that was really part of instinctual life and that it applied to us. - But Hilferding rejected that idea.

She said that while maternal affection isn't automatically instinctual, it could be brought about by physical contact between the mother and baby. Taking Freud's drive theory into consideration, which is based on the idea that organisms have instinctual needs that power certain behaviors, Hilferding put forward a new idea about instinct. Evelina List explains. If it's not sort of something inborn,

then obviously it needs a relationship. And it's the relationship to whom? And of course, it's the mother. So the life-saving and drive-inducing comes from the relationship between mother and child. And then, of course, that capacity of the woman is nothing innate either. It has to develop.

And so the whole drive dynamics is something psychosocial alongside, of course, a biological basis. Because, I mean, psychoanalysis is not some esoteric belief. But of course, without a body, there's nothing. Hilferding brought the body right into the room and talked about birthing. Let's pause for a second and remind ourselves of the year. It was 1911.

In front of a group of well-educated but relatively unenlightened men, men who knew little about internal female struggles, there was Margaret Hilferding talking about the sometimes brutal physical and emotional aspects of motherhood.

and she was putting it in psychoanalytic terms. So she tied, which I have long felt, but that the quality of the birth experience probably influences the relationship to that child.

So Helferding was quite observant about that and talked about the psychological surround of the mother, but also the physicality of the act of birthing. It was shocking to her audience. And when she gave that presentation at that time, this all-male group,

did not like it. They did not like it. And we still do it, but they definitely did it. We still idealize this motherly love, as she called it. And they were not having it. They completely rejected her presentation. Motherly love to this group would seem to have a particular definition, one that was inborn and could not be challenged.

even using a psychoanalytic framework, as Margaret did. Evelina List again. Psychoanalysis is interested in the body as something that has meaning.

It's just the symbolized body that really counts in psychoanalysis. So the interaction between the mother and child is central in Hilferding. And she said, this is, I find absolutely brilliant. She said, if we assume an edible complex in the child,

It finds its origin in sexual excitation by way of the mother, the prerequisite for which is an equally erotic feeling on the mother's part.

It follows then that at certain times the child does represent for the mother a natural sex object and so on. This notion would have been startling to the men in attendance because it pushed Freud's idea of the Oedipal complex in a new direction, a direction that involved the mother and child relationship as primary. Another thing that she said was that there exists between a mother and child certain sexual relationships which must be capable of

further development. Margaret was not only charting new territory, she was laying down the path for further exploration. She brought long overlooked desires and fears of motherhood into the conversation. According to Clara Nashkowska, She talked about how the relationship between a mother and her fetus or baby or child is complicated, complex, nuanced and ambivalent.

Ultimately, she took on a subject that is still taboo, the existence of women as sexual beings before, during, and after motherhood. Candace Dumas points out why that was problematic. That was radical thinking for both

both women and men at that time, the different reactions women have to motherhood, which back then was also not spoken about. Today, it's still difficult to speak about. I see patients in my practice that if they are not in love with their babies from day one, they feel immense guilt that they are doing something wrong as a woman and as a mother. I teach my students about this and I ask them of maternal instinct and a lot of them think, no, no, no, that's a natural thing.

They don't see it as a social construct, which it actually is.

As hard as it is for us to grapple with these conflicting feelings today, it was practically crippling for the esteemed members of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, who had a very particular idea of who and what women should be, even in this extremely progressive bubble. They were living in a country where the cult of the Virgin Mary had been the norm for centuries. Women's maternal love was not only ingrained, it was a cultural necessity.

I think personally they experienced this as a threat. They held tight to the idea that maternal love was inborn, and anything suggesting otherwise was due to the fact that a mother was, in the words of one member, degenerate. To this, all Margaret said was, it just won't do. I think that she definitely was disappointed. However, Hilferding was pretty tough-minded person.

But her presentation was essentially rejected. Even worse, it was erased. Possibly by Freud himself, which wouldn't have been unusual. People who broke from Freud...

Almost every one of them had more to say about females than Freud. And that seemed to be a kind of unconscious threat. And when she said, "This won't do," I think that that would be the beginning of a lot of discord. Within months, the group experienced some seismic shifts, ultimately resulting in a splinter group who followed Alfred Adler.

As for Freud, his true feelings about Margaret may have been expressed in a letter he wrote to Carl Jung.

When she left the group, along with others, Freud was not unhappy to be losing their only female member. He referred to her as their only "Doctor-vibe," which, according to Evelina List, he meant derogatorily. She goes so far as to say that he was calling Margaret a "bitch of a doctor." Never one to depend on a man for approval, Margaret moved on. But on the basis of mother love would be Margaret's only contribution to the field.

Its impact, if it had one, was brief. This paper essentially disappeared. For a hundred years, nobody read any of her work. And these themes basically disappear from psychoanalysis.

Margaret Hilferding did not need the validation of a group or dependence on its leader to do what she believed in most, caring for her patients and fighting to uphold the values of social democratic politics. For her, there was still plenty of work to do.

She is a counselor because part of her service, mostly for the working class, for the poor, is counseling on sexuality and birth control and sexual relationships and so on.

And so that is what she returned to: serving her patients, fighting for their rights, to birth control, to abortion, to a living wage. In just a few years, the First World War began. Margaret continued to raise her two sons.

And when the war was over, the Social Democratic Party saw some success on behalf of working people. She was a regular activist in the party and gave speeches in many fields. And she was organizing the social democratic doctors and she founded that society. And she was, of course, a women's rights activist. This period of time was known as Red Vienna.

It lasted through the mid-1930s and saw the rise of socialist organizing and workers' power. She was very involved in political life, one could say. But as she went up against the Catholic Church to fight for these rights, Margaret experienced considerable heartbreak when her son Carl converted to Catholicism at age 19. His baptism and confirmation

coincided with a presentation she gave where she was criticizing the role of the Catholic Church in relation to abortion laws. Big disappointment for her. Despite this, Margaret believed deeply that education itself was a source of political power, as it had been for her. She really honestly believed that with enough education...

that anti-Semitism could be eradicated, that people could enlighten themselves beyond that, that wouldn't be important anymore. The gains of Red Vienna were short-lived. In 1934, the Austro-Fascists banned the Social Democratic Party and

and practically overnight, the entire country was ruled under the ultra-conservative, anti-Semitic, Austro-fascists. Margaret was temporarily imprisoned and lost her public positions, her home, her practice, her source of income,

and her rights. But as the years wore on, and conditions for Jews continued to decline, she remained dedicated to helping people whose situation was worse than hers. Hilferding, she loved being a doctor, doing the work of a doctor, and Rothschild, you say Rothschild, was the only Jewish hospital that still existed.

And she was allowed to walk there. She was not allowed to use public transport. She was also not allowed to sit on a public bench. She worked there a few hours every day and then walked back. In 1938, Austria was annexed by Germany. Nazis entered Vienna, the streets lined with people waving flags. Hitler rode through the city, standing in an open car, appearing to be adored by all.

Everything that Margaret and the Social Democratic Party worked for was over. Margaret, who was 66 at the time, was forced to live in a Jewish old person's home in Vienna. This is what it was called. But it was actually a filthy, overcrowded prison for older Jews who had been forcibly moved from their homes to their homes.

and whose rights were taken away. Here's Candace Dumas again. It seems as though in these old age ghettos, she was really able to, without a lot of resources, she was still able to try and provide care, medical and psychological care, to the other people imprisoned there as well.

Her son, Peter, managed to escape to New Zealand. And even though Margaret had a narrow window of opportunity to leave for France, she didn't take advantage of it. She was dedicated to her work. She would leave when she was ready. And unfortunately, when she was ready, it was too late. In 1941, systemic mass deportations of Jews began.

In the end, Hilferding was a woman who lived according to her ideas and convictions. But her foray into psychoanalysis, as brilliant as it was, was cut short. In total, the notes on her one psychoanalytic paper take up just 14 pages of the four volumes of the minutes of the Psychoanalytic Society. But that doesn't mean we can't learn from that paper now. She really was...

a pioneer here and she really had prescient ideas. So the question is, how is it that a paper written more than a hundred years ago is still ahead of its time? The forces working against Margaret Hilferding were the same forces that have been working against women throughout time and that work against us today. In Rosemary Balsam's words, it's due to a conspiracy of silence.

I mean, the silence has been there for centuries upon centuries upon centuries. And I think that it's very much to the advantage of male power that people are in a conspiracy of silence. The silencing that Margaret Hilferding experienced came long before the Holocaust, but eventually that would silence her too.

Which brings us back to the suitcase and the letter that was found inside it when her son Peter returned after the war. My dear boys, dear Carl, dear Peter.

She wrote this letter in June 1942. It was her 71st birthday. The next day, she would be transported to Theresienstadt, which served as a temporary holding place for Jews being moved to camps farther east. Now, it seems that my departure is getting serious after all, but not closer to you and not under favorable conditions.

She put this letter in that suitcase, which she managed to get to her sister's house on the outskirts of Vienna. I expected that we would probably never see each other again, that we would never hear from each other again, that we wouldn't even know where we are. I had to expect that, but it was still a long way off. Margaret was taken from Vienna to Theresienstadt by train.

There, Margaret might have seen her brother, Otto Hoenecksberg, who died in Theresienstadt shortly afterward. It is now over a year since I received a Red Cross reply to my letter from Peter, and two months since I've heard from Karl.

Margaret did not know that her son Karl had been murdered in Auschwitz, or that her ex-husband Rudolf had been tortured to death in Paris by the Gestapo. I have not been so bad on the whole, and have always kept my head up until now. Will that be possible any longer? I certainly intend to, but it will be very difficult.

Not long after being transported to Theresienstadt, Margaret was sent to Treblinka, a concentration camp. And now it's my 71st birthday. I don't want to be sentimental, but it's actually a sad day for me. Upon arriving in Treblinka, Margaret was murdered almost immediately. You can't complain.

One shouldn't complain if one has to leave life soon. It's about time. Although she would disappear, her work was not for nothing. Eventually, her son Peter would read this letter and understand the depth of his mother's love and her remarkable story. A story where she was not lost, after all. The only happiness is that you are on the outside, mother.

On January 27th, we observe Holocaust Memorial Day, and this year is the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. We dedicate this episode of Lost Women of Science to all those, like Margaret Hilferding, who did not survive. ♪

I'm Marci Thompson, and I produced this episode. Deborah Unger was senior managing producer. Echo Finch designed and engineered our sound. Our music was composed by Lizzy Yunin. We had fact-checking help from Lexi Atiyah. Lily Weir created the art. Thank you to our co-executive producers, Amy Scharf and Katie Hafner, and to Aon Bertner, our program manager. Thanks also to Jeff DelVisio at our publishing partner, Scientific American.

Lost Women of Science is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Ann Wojcicki Foundation. We're distributed by PRX. For a transcript of this episode and for more information about Margaret Hilferding, please visit our website, lostwomenofscience.org, and sign up so you'll never miss an episode. And while you're there, don't forget to press that all-important donate button. See you next time.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪

Hi, I'm Katie Hafner, co-executive producer of Lost Women of Science. We need your help. Tracking down all the information that makes our stories so rich and engaging and original is no easy thing.

Imagine being confronted with boxes full of hundreds of letters in handwriting that's hard to read or trying to piece together someone's life with just her name to go on. Your donations make this work possible. Help us bring you more stories of remarkable women. There's a prominent donate button on our website. All you have to do is click. Please visit LostWomenOfScience.org. That's LostWomenOfScience.org.

From PR.