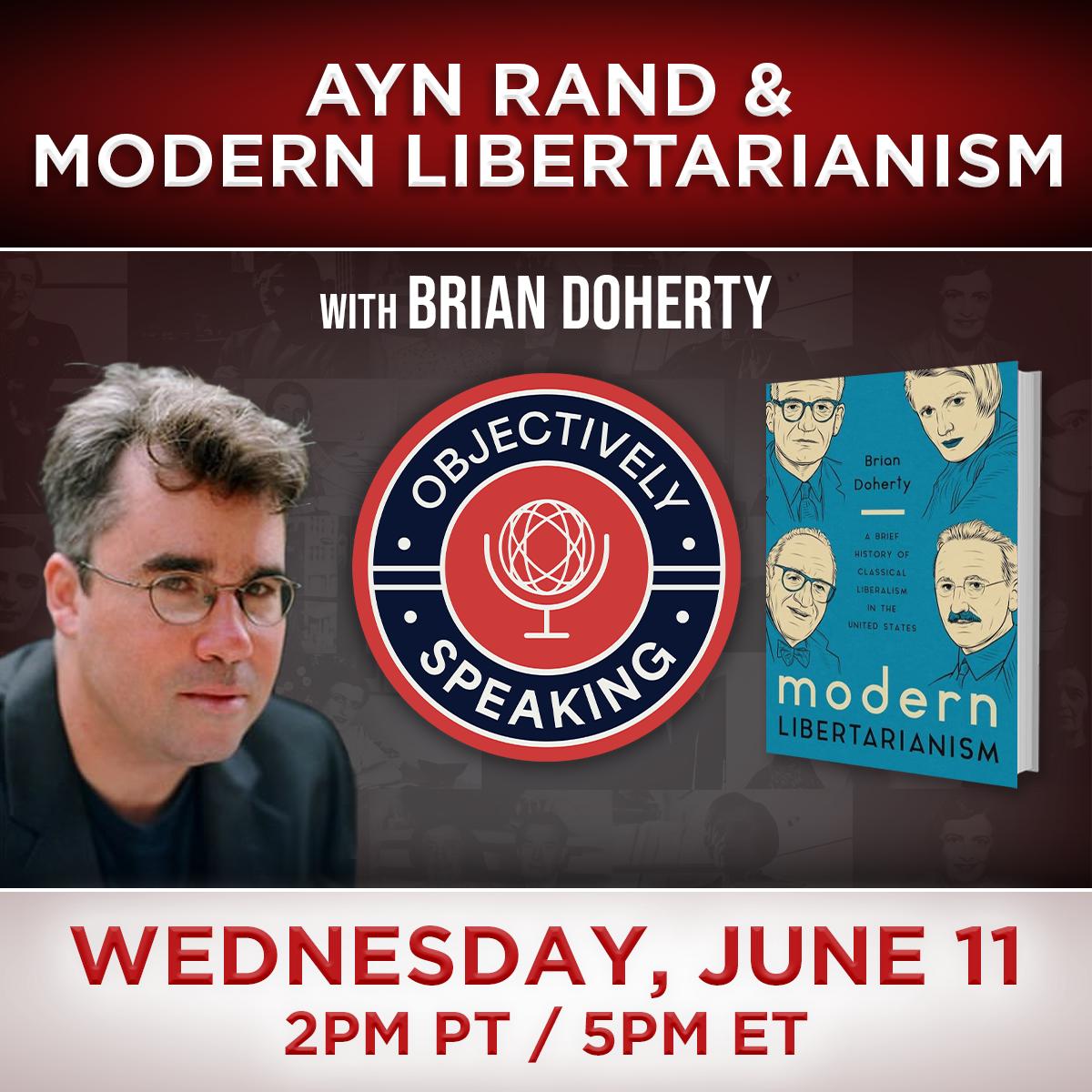

Ayn Rand & Modern Libertarianism with Brian Doherty

The Atlas Society Presents - The Atlas Society Asks

Deep Dive

- Brian Doherty's first Burning Man experience was in 1995.

- Burning Man's origins are linked to the Cacophony Society.

- Doherty views Burning Man through a libertarian lens.

Shownotes Transcript

Hello everyone and welcome to the 257th episode of Objectively Speaking. I'm Jag. I'm the CEO of the Atlas Society. I am so excited to have Brian Doherty join us today to talk about his book, Modern Libertarianism, A Brief

of history of classical liberalism in the United States, which provides a concise, thorough account of the intellectual roots of the American libertarian movement with helpful summaries of key figures and institutions and events, as you can see from all of my bookmarks. I thoroughly enjoyed this book. Brian, thank you for joining us. Thank you so much for having me. It's a pleasure.

So last year I attended my very first Burning Man with my friend Grover Norquist. So I've got to ask, what is your playa name and when did you do your first burn? I do not follow the convention of a playa name. I am Brian Dougherty here, there and everywhere. I started doing the Burning Man in 1995.

we don't need to get too deep into the burning man thing but one of the organizations that helped move it to the black rock desert playa was a sort of prankster art organization called the cacophony society that i was a member of in los angeles in the mid 90s um burning man's propaganda back then and maybe even now uh very successfully sold the notion that this was a very very hazardous dangerous unpleasant place right you know it's in this desert playa

Nothing but crack dust everywhere, prone to destructive windstorms, can get above 100 in the day, can get below freezing at night, all that. So the first year I heard about Burning Man 1994, their propaganda actually scared me from going because I'm not a particularly rugged or outdoorsy person. So I could have gone in 94, but didn't. 95, you know, there was a woman who I was working with on a magazine who convinced me I should do it. And I did it.

Fell in fascination with it. I've gone every single year since that the event has actually been held. And then even one of the two years during the COVID scare, I went to an event like Burning Man that was not officially Burning Man, but held in the same place. So I became a lifer. I did...

see Burning Man through a libertarian lens as I see, you know, everything, you know, as a, you know, since my brain got

sold on this whole liberty thing when I was in my late teens. I tend to see everything through that lens. And you may know this, you may have had this experience if you talked to people in the libertarian world about, oh, I'm thinking of going to Burning Man or I did go to Burning Man. There's a fair amount of writing it off as something that's really hippie or really commie or

There are a lot of hippies there. There are a lot of commies there, undeniably. But the root of it, as you might have found, is extremely libertarian, even anarcho-capitalist in a way, because it's a ticketed event and all that, and it's a party, and it's a festival, even though they hate calling it a festival. It's not really a bad word for it. But it's also a city that we pay for the city services,

by buying a ticket. The city services are kind of minimal. They involve the best sanitation solution that the Black Rock Desert allows, which are port-a-johns with little sanitizers outside of it. It provides art funding. It provides a little bit of private security, you might say, in the form of Black Rock Rangers. And people have had bad experiences there, but

In general, it's a remarkably peaceful, remarkably fun,

private, you know, chart, you can almost call it a charter city in a way, because it has its little set of principles that we're all supposed to follow. And it works remarkably well. And certainly the libertarian vibe not only dominates the actual experience, but you also will meet many fellow libertarians there, some from the San Francisco tech world, some from the general, you know, anarchist performing world. I recommend it to all libertarians if you think you can stand

Yes. Well, I was given a pliant name. People will not be surprised that it's Dagny Taggart. And I was delighted to find out that the CEO of Burning Man, Marion Goodell, is a

rip-roaring Ayn Rand fan. Her father had a company called American Brass and he had a private rail car which he called the Dagny Taggart. So she and I have become closer and I expect I will be there again this year, Brian, so maybe we can meet up on the playa. Now of course you wrote about Burning Man in your best-selling book, This is Burning Man. So

maybe unpack a little bit more how that experience may have informed your view on decentralized government, governance, personal liberty. I mean, to me, yes, there was certainly a fair amount of hedonism, but it was also a demonstration of what man can create without overweening government interference and also an artistic

creativity outpouring and also sort of a way of individuals trying to trade, to find opportunities to benevolently provide value. What was your take? Yeah, that's hedonism, but if you've ever seen

picture of it or video of it. It does help to remember someone brought or built generally within the period of about a week or less and having to drag everything it took to build it. If you're in the Bay Area, it's like four to six air. It's all coming from very, very, very far away. It is an incredibly hardworking place. It is also a result of

the wealth that American modernity throws off because on site, but obviously like any human endeavor, like a lot of commerce in the basic sense of

You are trading your labor and skills with someone else to get something. Like every RV out there, someone either bought or rented, right? Every stick of wood that was used to build something, someone bought from someone else. It's one of the most glorious little bubble bursts of American quasi-capitalist modernity in the first place. So anyone who is there and is griping about capitalism is performatively contradicting themselves.

in the first place. And secondarily, it's like the wealth that allows us to play that way is a result of capitalism. And as I was saying, the way capitalism

the civic experience is structured is purely market. We pay an organization a ticket price, pretty high one at this point, in order for the right to be there. They actually have a remarkably strong border for a private city and they provide a minimal amount of services and allow people to make free choices about how to behave with an ethos

that we have adopted by going there, that we are there kind of to delight each other in a way. You know, one of the slogans of the event, one of the principles that is supposed to guide the experience is no spectators. You're not just supposed to go there and gawk at other people's stuff. Though also, to be honest, like,

Everyone who's going there doing stuff, they want spectators. So it's not like you can't be a spectator part of the time. In fact, you're definitely being a spectator probably most of the time. But the city is not going to be as interesting, as full of fun art, as full of fun experiences, as full of fun interactions if you don't shift your attitude to go, oh, I'm also supposed to help.

I'm not just supposed to watch the cool things other people do, although I should be watching the cool things other people do. I'm also supposed to do something cool myself, help out, be interesting, be friendly. And it works remarkably well. Like anyone, you can have a bad experience there like anywhere else, but for the most part, you don't.

crime of the sort a libertarian would respect is not unknown out there, but it's not dominant. You know, things can get stolen, people can get assaulted, it does happen, but there's not a lot of it. And I think a lot less of it than in any gathering of about 80,000 people, which is how many people are there. So I do think

Watching Burning Man, experiencing Burning Man, if you're paying attention, should both make you really feel a great deal of affection for the wealth that capitalism can throw off and a great deal of affection for the idea that people can gather without government in a real sense, without central planning in a real sense, and just...

get along and do interesting things and make an experience that's actually more interesting than any average seven days anywhere else. I have always seen it as a very libertarian thing. To the extent it's gotten less so, it's gotten less so because the existing authorities of the world, from the federal government to local sheriffs, do insist on

on both being there and taking their chunk of the proceeds. There's nothing that can be done about that, but I would maintain for the most part, they're not needed. They are genuinely parasitic on the experience. There's just unfortunately no way to do it without them in the world we live in when you need a piece of land Burning Man needs, because a lot of things get set on fire there. Burning Man, so you kind of needed a piece

You do, but you know, now with some talk about the potential of selling off some federal lands, I wouldn't be surprised if we find ourselves in a place where Burning Man is actually able to own part of the land that they now have to, you know, as you correctly described, have to pay obeisance to the Bureau of Land Management. And so we'll see.

To switch topics for a moment, graphic novels are a fundamental component of our strategy here at the Atlas Society to reach new audiences with Ayn Rand's literature, with our adaptations of Anthem, Red Pawn, Top Secret. You have explored the underground comics

in your book, "Dirty Pictures." So what drew you originally to these rebellious artists and do you see parallels in their fight against censorship and modern libertarian battles for free expression?

Yeah, absolutely. Comic books in general, I was just a normal American kid who in 1975, you know, on the way to the beach with my parents, you know, picked up a superhero comic off a rack in a 7-Eleven and fell in love. So I've been like a comics guy all my life. I was not an underground comics guy all my life. And in fact...

As the title of my book, if people aren't familiar with what underground comics mean, the simplest way to put it is a set of comic books and comic art and cartooning, mostly begun in the mid to late 60s, that in a world where all the comics any American had ever seen were either comic books, which were under the Comics Code Authority, or comic strips in a newspaper that had to be

anodyne enough that, you know, a typical suburban dad at the table reading paper is not going to be offended by it. Comics were very limited in how they could express certain things that I summed up in the phrase "dirty pictures."

Underground comics were not always obscene, but they could be obscene and they sometimes were obscene. They dealt with politics, often radical politics in a way that comic code, comic books or newspaper comic strips did not. And I argue in the book that even though

If you look at the actual original underground comics of the late 60s and 70s now, a lot of it just seems disturbingly crude or disturbingly politically incorrect in a way that, you know, even most sort of hipsters would not tolerate today. That the very fact that an organization as respectable as the Atlas Society is delving into graphic storytelling and cartooning as a way to sell political ideas, this is all rooted in the undergrounds because, again,

The Underground, by bursting every barrier of propriety and what sort of topics comics could cover, opened it up not just for stuff that was naughty or stuff that was going to make certain people want to censor it, but just

anything comics can do anything now because the underground cartoonists did what they did so comics are now respectable literary things they're winning booker prizes you know they're getting nominated for national book awards cartoonists are getting guggenheims cartoonists are getting pulitzers uh nearly every major new york trade publisher publishes graphic novels like they they

The Underground's innovations took comics from being something that inherently was limited or even aimed at children in the case of comic books and made it a perfectly legitimate art form. And the sort of main heroes of the book are Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman. Art Spiegelman is most famous for Mouse, a book that is still getting in the press to this day for being objected to or censored from school libraries.

If people are not familiar with Mouse, it is a retelling. Spiegelman's parents were both in concentration camps during World War II, and it's a retelling of his parents' story using the cartoon signification of

Jews are mice and the Nazis are cats. And it's, you know, when you say it, and my book tells the story, when you say it, you say the idea, it sounds almost ludicrous. And in his attempt to sell the book, he ran into a lot of that from normal book publishers. Like this is just absurd. This is childish. This is silly. It will never work, but it works remarkably well. The book was an amazing success. It won him a Pulitzer. It sort of laid the groundwork for everything

like serious and respectable that's happened to comics since in the world of galleries in the world of publishing and I did think it was interesting culturally to show that

the way to make an art form serious and respectable was at the beginning for it to be often very unserious and very unrespectable. That chopping at the sort of root of the human id is a little hard to explain if you don't get it. Like if I was trying to explain it to my mom, I think my mom would just be like, what are you talking about? It's just, you know...

filthy cartooning and like yeah it is that's one thing that it is but it also is

allowing everything human to be expressed in an art form, which just didn't happen in comics and cartooning until these guys came along. So I think it is a vivid example of how doing things that were literally against the law, like people actually did get arrested for selling these comic books in the late 60s and early 70s. They literally, what they did was illegal, but what they did shaped and expanded an art form that I think most Americans now understand is not just childish, is not

stupid and can do anything. But the way humans are, it's like the joke you'll always hear about any new technological innovation. The first thing you're going to do with it is do porn. And it's not always exactly true, but there's a lot of truth to it. Like there are certain root things about being a human that society, often for intelligent reasons, you know, tries to sort of

suppress a little, repress a little, shuffle off to the side a little bit. But like, if you're going to be a fully expressive human artist, you have to be able to deal with that stuff. And the underground cartoonists broke the law to allow cartooning to mature in an ironic way, almost through being childish. Yeah, yeah. Well, they, you know, are an example of those who came before laying the groundwork for those who would later elevate a genre to a higher place.

plain and of course your book, Modern Libertarianism: A Brief History of Classical Liberalism in the United States is also a history of those who came before and paved the way. Now, Mark Twain famously once said, "I didn't have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead." What were the challenges of

writing a this more concise account of modern libertarianism as opposed to your longer more comprehensive history radicals for capitalism yeah um super challenging and you know if i were being called to account you know at the gates of heaven or whatever if there is a heaven and sort of asked you know which which is the

The more major work, I would have to say Radicals for Capitalism, the longest one, feels more significant. But especially, you know, that book was published in 2007. And especially as we've entered the kind of podcast and social media age, I definitely recognized and the Cato Institute who published this new one, Modern Libertarianism, recognized that.

there was probably room for a more concise swing at this material. And that is actually far more likely that someone, you know, under the age of 35 or whatever in 2025 is more apt to read this than to read radicals for capitalism. I mean, ever since that book came out, I've had people just sort of say it's length is daunting and I understand this length is daunting, but the length of modern libertarianism is not daunting. Um,

It's all reduction, right? A lot of the stuff that might have been in radicals and is not in modern libertarianism, some of it is almost the comedy a little bit. Libertarianism, like any radical philosophy, tends to attract radical people in the simplest, crudest way. It attracts people.

A lot of strange people, a lot of weirdos. Radicals for Catholicism sort of explores the strange weirdness of the world maybe more than modern libertarianism does. I think modern libertarianism I think wants to be more just like the cream of the crop, the real important stuff, not the side roads. Like focus on the major figures who can and are still read rewardingly to this day. Your Ayn Rand's, your Hayek's, your Mises, your Rothbard's.

On the cover, you'll see Barry Goldwater, interestingly, a figure who I wouldn't say is a libertarian, but the reason he's on the cover is because his role in injecting libertarian-ish ideas and spirit into actual electoral politics in the early 60s was brain-blowing because the libertarian movement, such as it was in the 40s and 50s, did not even dream of actually impacting

real electoral politics. It was such a derided, such a hated, such a completely underground philosophy that even the people who advocated it professionally mostly understood that we are not ready for prime time in any way, shape, or form. But Barry Goldwater's success, again, with ideas that were not libertarian across the board, but libertarian-ish, helped change that. And I also found in researching

uh radicals originally that if you were a professional libertarian and you were like a teenager during those early goldwater years you almost certainly went through a goldwater phase goldwater was somewhat of a hero to you um uh going far i feel a little a little bit here so yeah i think like in doing the story shorter

focus on more of the stuff that stands the test of time and of enduring interest to anyone who understands liberty, maybe some of the more entertaining and wild and silly stuff

uh, got chopped. I, I definitely still would like to tell anyone who is very interested in this stuff, Radicals for Catholicism is still certainly worth reading. Uh, Modern Libertarianism is, is the new one and, and, and probably an easier thing. And I, I actually think it, it wasn't intentionally written as a primer, but I sometimes refer to it as a primer. I think it, Modern Libertarianism is a great book.

for like a college student thinking about politics, even a high school student thinking about politics. And design-wise, Jennifer, I'm not sure what our age difference is, but when I was in grade school in the 70s,

We had lots of little books that looked like modern libertarianism. So I was actually excited when I saw it. I'm not a guy who knows how to design anything that looks good or interesting. So I was very pleased that the people at Cato designed the book to look to me like something that a kid in school would want to buy and read. And I think especially if you're like an adult and you have youngsters in your life.

I think it would definitely be for the Atlas Society's gulch-gulch type student audience. Now diving a little bit into the substance of the book, obviously the audience here knows that at the Atlas Society we are promoting the literature and philosophy of Ayn Rand, which of course includes her strong moral case for capitalism. Now in modern libertarianism you write libertarians

believe either that people have a right to be left alone if it doesn't harm others, or that things will on balance work out best that way, generating the most varied and rich culture, or more commonly, both, as you might

I suspect. I'm of the belief that if we fail to make the moral case for capitalism, this utilitarian case puts us constantly on the back foot. What is your view?

doing what I've done for most of my career, which is trying to explain libertarianism to as wide a world as possible. I am what you might even consider Polly Annie-ishly big tent because I've noticed, and I'm confident this is true, that different arguments for libertarianism are going to appeal to different people. Like there is a definite range of human types, right? So

I don't want to say like this is the way. I think there has to be a lot of different ways. I do want to give Ayn Rand all the credit here because Ayn Rand, as I said, I think most libertarians believe both of those things. To state it again, they both believe that.

liberty, leaving people alone to follow their own will and their own choices as long as they're not directly harming other people's personal property is the right thing to do. Humans are definitely moral animals, absolutely. I've occasionally met a person in life who

seems to think that they don't follow a moral code, but I think even they, as Ayn Rand would point out, you know, you do. You might be ignorant of it. You might not have reasoned it through. You might not have figured out how to do it non-contradictorily, but you are following some sort of sense of morality. But as Ayn Rand pointed out, she argued that the nature of human beings and the nature of the human mind are such that

Being free and allowing other people to be free is what is going to lead most of the time to the best utilitarian result, which is why I think most libertarians, even if they're not specifically influenced by Iran, do believe both things. And they don't think it's like a weird coincidence. It's not just, oh, how convenient for you libertarians that the thing you

you think is right you also think is going to place well no as ayn rand argued wonderfully there's a reason for that it's the nature of humanity the nature of the human mind the nature of how humans have to cope with the reality in front of them how they have to take the things of the world and use reason and logic to turn them into other things that help meet our needs like it's just it actually is a fact a randian would argue and i believe as well that

following libertarian political principles is actually what is going to lead overall to the richest, most wealthiest, uh, most diverse, most choice filled, wealthiest, uh, society. Um, and I've actually seen thinkers say that, Oh, that's a cheap rhetorical trick libertarians use to, to mix the utilitarian and the moral, but it's not like, uh, you may think Rand didn't prove her case, but, uh, she made a really excellent case. Uh, Murray Rothbard influenced by Rand, uh,

in many ways, though he soft peddled that later because he got mad at her, kind of worked in the same vein, that sort of Aristotelian natural rights, natural law tradition that shows why the nature of humanity requires or demands that we be free and that we let other people be free. And so, yeah, I do think most of us believe both, but it's not just like convenient or coincidence. It's the nature of humanity. Right.

One person who may or may not have believed both is Ludwig von Mises and his advocacy of economic and personal liberty is something you describe as explicitly utilitarian, springing, "Not from a metaphysical belief in rights, but because liberalism delivers the greatest wealth and abundance for all." Do you think this more utilitarian approach contrasting with Rand's moral approach,

may have contributed to their somewhat more contentious relationship.

You know, Mises and Rand are a fascinating couple of people to consider. A lot of the lore about the two of them, when you dig into it, comes down to just like an anecdote that someone remembers and you can't always be sure it's 100% true. Because, for example, I've seen a story, and I'm pretty sure it's in both of my libertarian history books, in which I think Hazlett, the book, knows this for sure, my

We write books because so the books can be smarter than we are. But I think it was Henry Hazlitt who told Rand that he heard Mises refer to Rand as the bravest man in America. And Rand was just like, man, did he say man? And just was like delighted, just like it warmed her heart. And Rand in sexual politics and gender politics is a very complicated thing.

Again, the thing we're not going to settle here, but it's amusing that we saw her in a masculine way. So they're definitely, and I've seen letters from Mises, private letters in which he absolutely was an enormous fan of Atlas Shrugged, an enormous fan of Ayn Rand. And Mises was one of the few economic thinkers who, you know, the organization that was spreading objectivism in the 60s, the Nathaniel Brandon Institute, would recommend Mises' work. And again, this is...

I think, again, forgive me if I'm getting this wrong, the book will get it right. So I don't remember if this is something Rand wrote or something someone remembered Rand saying. But when someone would press Rand, it's like, come on, Mises is so wrong on so many things when it comes to objectivism.

She actually said something like, "You know, he's done so much. He's done so much good. I'm gonna leave him alone on that." But on the other hand, I've also heard one person who had been in Rand's inner circle and became estranged from Rand, as many in her inner circle did. And I take this with a grain of thought because this was written in a letter in which this person, who I'm not gonna name, was obviously very much just writing out of anger at Rand.

said something like, oh, I never heard Rand refer to Mises as anything other than like that damn fool or something. So there was a lot going on. But I think for the most part, Rand did understand

in certain cases, that there were people who she would give a break on not understanding and grasping the full edifice of objectivism and recognize that they did a very positive thing for spreading intelligent economic thinking. And that's what she thought of Mises. But definitely, she could never have been a full-fledged Misesian. Mises could never have been a full-fledged objectivist. But perhaps in a lesson for all libertarians, they could and did promote and praise each other's work, despite not agreeing with it all the way down the line.

I love that very much in consonance with the open objectivist approach that we take here at the Atlas Society. And that includes a lot of

debate and um dialogue so in that spirit here we are halfway through i am going to get to a few of the questions that have been coming in um ann m asks did the mises caucus take over the lp because the old guard was weak on covid and the 2020 riots you do write about this in in your in your book yeah and i i've written about it i've written about that point um

It's a little bit in the new book. There's a lot more of it if you just Google, you know, I write for Reason Magazine. I've written a lot of things on Reason's website. If you Google, like, my name, Mises Caucus, whatever, you'll find some stuff I've written about it. All, you know, social and political events are multi-caused, but what you just said, I think, is certainly a fair argument.

way to consider it that i mean on the most very basic level the mesias caucus was able to take over the party because they were able to organize well enough to get

a bare majority plus of delegates who showed up at the Libertarian Party Convention in 2022 who supported their beliefs. But yes, I think the reason they were able to succeed in doing that is the perception. And I don't want to say here that I agree with the perception, but they definitely sold the perception that the LP's previous management was not hardcore enough about fighting COVID tyranny, even though the 2020

20, yes, 2020, the 2020 presidential candidate, Joe Jorgensen, told me for a reason that she considered COVID tyranny like her main issue. So it wasn't like the candidate wasn't against COVID tyranny, but they felt the party didn't mess it strongly enough against it or whatever. And yeah, there was also, I think, a general right-wing-ish cultural bent of the Mises caucus libertarians,

that helped organize them, that helped inflame them. And I think you can see this clearly in the fact that many high-level Mises caucus people, including the woman who was heading the Libertarian National Committee with the MC's support, Angela, sorry, Angela McArdle, absolutely became full-out Trump fans in 2024. So yeah, that's...

There's again, you can find more of this in more depth by googling my name. We'll put that link in the comments. Okay, I Like Numbers asks, "How important is the underground or anti-establishment? How important is that an inherent part of the liberty movement?"

You know, I think there's a way, and certainly when I was a collegiate libertarian and even like a high school kid, starting to get the idea of what political liberty meant to me. Like it was delightful for a young person, and I think still is delightful for a young person especially, to feel like a rebel, right?

I feel less like a rebel nowadays, but I just think it is a fact that if you believe in libertarianism and you're actively promoting libertarianism, you are a rebel in modern culture. You're maybe less of one than you were in the 1980s or 1990s. Libertarianism is made

amazing inroads in the field of tech, in the field of social media, in the field of the hottest, newest media trend of this decade, past decade, the podcast world. Libertarianism is a lot more dominant there. So maybe you feel less alone. And the definition of what underground means is

you know, underground people, artsy people love, love, love arguing about that stuff and love always feeling that they're more underground than the other person. And, you know, Burning Man's another example of this. When I got into Burning Man in the mid-90s, it was fair to think of Burning Man

as kind of an underground thing. It's definitely not accurate to think that way about it any longer. It's an entrenched part of American culture. It's almost like Mardi Gras. It's just like this interesting wild party that happens every year and everyone knows about it and everyone has an opinion about it.

And as an old man working for Reason Magazine, it's probably almost definitionally true that there's a lot of like truly underground things happening that I don't know about yet. And I'd like to know about them. So I do think with a philosophy like libertarianism that is still in opposition to the dominant culture, still in opposition to government, still in opposition to most media, that it's kind of all underground in a way. And there's probably some real serious underground stuff

that by its very nature, I don't know about, but maybe you do, but I can understand as a cultural historian that it's out there and it's making important things happen that maybe won't be obvious to people like me for two, five, 10 years. - All right, Jackson Sinclair asks, "Question, do you think there was, were a special set of circumstances that led to the rise of libertarian thinkers? Do you think it's still possible in today's more polarized environment?"

So what were the circumstances that led to the rise of the modern libertarian moment?

I think the quickest answer to that is the New Deal, right? In the 30s and 40s, the Great Depression, the New Deal, World War II, saw a wave of government centralization and control and bloodshed and terror that a very tiny, and I mentioned this before, a very tiny, tiny body of thinkers with an audience that was a little better than, a little bigger than the number of thinkers, but honestly not terribly that much bigger than

were completely alone in seeing that there was something off-putting, wrong, or mistaken about this. And Hayek's very famous book, The Road to Serfdom, which came out toward the end of World War II, kind of does the best job of helping a modern reader understand this, because he really is looking. He's like, okay,

The Western powers, Britain and the United States, you think you're fighting fascism, right, in this war that's going on right now. But some of the things you were doing that you did both to allegedly fight the Great Depression and to fight World War II are actually kind of the same things that the fascists had to do in terms of centralization. So it was a warning, a very well laid out warning that war centralization, New Deal centralization was dangerous to liberty and it was dangerous to prosperity. And so I think

That's the intellectual historical environment out of which it arose. Now, you might be saying, and you'd be right to say, hey, in 2025, what the government is doing in many ways is wider and more controlling and more wealth consuming, even than what the government was doing in the 30s and 40s. And I think you'd be mostly correct to say that. And so the

conditions to create and maintain that rebellion are as strong as they ever were. And I think they have. I mean, especially if you read this book or read Radicals for Capitalism, you

I think it will be a very bracing and encouraging thing for anyone involved in libertarianism now to see how small, how abused, how derided, how hated libertarian thinking was in the 40s and 50s. It's so, so, so much better now. It's better now because thinkers like Hayek and Mises and Rand

and Rothbard and Milton Friedman were, had the gumption and had the will and had the strength of character and the confidence of their own beliefs to say like, okay, the whole world thinks I'm crazy. I don't care. I'm not crazy. I'm right. And I'm going to spread these ideas. I'm going to argue these ideas. I'm going to fight these ideas. And then they had, you know, Ayn Rand the most, but the other is plenty of disciples, followers, people who just were convinced by them. And it's not,

I have colleagues at Reason, Nick Gillespie and Matt Welch, who do a lot of arguing that I find somewhat convincing, but not always completely convincing about how the very realities of technology and capitalism change.

even within the sort of the case that government tries to keep us in. A world where our freedoms to live and make choices actually are still incredibly rich, you know, no matter how much of the GDP government is taking, no matter how many hoops you have to jump through to start a business or whatever. Like, it's worth celebrating because, like, we believe in capitalism, right? We believe in free markets. We believe they make the world a richer place. And even as constrained as government makes them, market forces...

human reason are so powerful that even constrained by government, they do amazing things. And it's good to be optimistic, right? I mean, I'm not necessarily temperamentally optimistic. So it's actually good that my intellectual work requires me to confront reasons to be optimistic. And even like I am definitely not one of these libertarians who sees a lot of hope or encouragement in the Trump thing. So I am

perhaps as dismayed by certain things about the political world today as I have been in my lifetime. But still, like, it's both good for your spirit and good intellectually to keep your eye on politics.

what's better, what freedom has already brought us, and to be able to point to that to help make the argument that an even more freedom is going to be even more better. And I think it will be. I've honestly lost track of where this question started. Sorry. Yeah, no, but, you know, we are biologically wired to over-

stress threats and problems. So it's something that here at the Atlas Society, we talk about gratitude as a virtue and a value because it

makes us look and try to find what is going well in our own lives. And just that very exercise of doing that gives us confidence that whatever challenges we may face, that we will be able to overcome them. All right, I'm gonna take one more question, but then I have so very many of my own.

And this is from Ilyushin wanting to know, Brian, what do you define as modern libertarianism in comparison to classical liberalism? It's the tradition, as the book argues, that kind of began in the 40s. The organization that I consider the first distinctly modern libertarian organization

educational organization is the Foundation for Economic Education, which still exists. We often call it FEE. It's founded by Leonard Reed. Its story is told at some length in modern libertarianism. The distinction that I think is most important in, you know, and I think it's fair

for a modern libertarian if he wants to call himself a classical liberal for whatever summoning of a spirit of the past that he respects of your spencer your mill or your smith or whatever or whether he just thinks it's uh you know works better rhetorically

because there might be things attached to the term libertarianism that he doesn't like nowadays. Like, it's not unfair for a modern libertarian to call himself a classical liberal. But the idea that has been injected into modern libertarianism

Even though Mises did not believe it, Ayn Rand did not believe it, Friedman did not believe it, Hayek did not believe it, but the fifth figure who I posit is the five foundational figures of modern libertarianism. Murray Rothbard did believe it, and he was a very good seller of it, and I think it's really...

defined what makes American libertarianism distinct from classical liberalism, which is the anarchism element, right? Rothbard believed not just in a strictly constitutionally limited government, he believed that true liberty meant that there was no institution that actually had, you know, the monopoly on the legitimate use of force. And that idea and kind of Rothbard's personality, I think we might be talking more about Rothbard later,

injected a rebellious and radical

sort of strain in people who call themselves libertarians. And of course, not everyone who calls himself libertarian isn't an anarchist or an anarcho-capitalist in the way that Rothbardians use it to distinguish themselves from the anarcho-communists. But I think it's fair to say that Herbert Spencer, you could argue a bit, right, to ignore the state. We can't get into that. But for the most part, the classical liberal tradition was not

the classical liberal tradition maybe had more respect for democracy as a decision-making mechanism than the Rothbardian anarchist strain has. And I think that's the best way to say it. And a simpler way to put it is, go on.

Go on. I would agree. But you said something that was a bit provocative, perhaps for this audience. In your book, you write that, quote, "Ayn Rand, whether she admitted it or not, was a libertarian, one of the most important ever." Now, while she herself may have rejected that description, probably rather strenuously, why do you think it fits?

Because Ayn Rand's politics, distinct from her epistemology or anything else about her, all the other things that she actually thought were more important than the politics, because in Randian thinking politics, epiphenomenon is probably not the right word, but you have to build from ontology and epistemology before you get to politics. But the politics that she got to were libertarian, like by any definition of what libertarian means, a belief in government limited only to the defense of people's

personal rights and property and ran by playing with the idea of voluntary taxation. Actually, in a way, I think

got close to anarchism. Like she believed, and she has very good arguments for it, that you had to have one institution, right? You couldn't have multiple institutions using force. So she believed there should be just one, but she did believe it should be funded voluntarily. So yeah, I mean, it's as simple as that. Like Rand's politics were libertarian. What she didn't like was that people who came across calling themselves libertarian, A, she thought, and in many cases she was right, got their politics from her

in almost a stolen concept way because they didn't get to them the way she thought you had to get to them. So she's like, hey, you're kind of wrong and you're plagiarizing me. And also there were lots of people who call themselves libertarians who were not objectivists. And she thought you ought to be an objectivist. So it irked her to be lumped in with people who

Might have shared her politics, but were not full-fledged objectivists. So I understand why she didn't like the term. And given her personality, I understand why she railed against it. But I think as an outside intellectual looking at this, it's like, how do you describe Ayn Rand's politics? Well, libertarian. That actually is the accurate way to describe it. Okay.

Okay, I get it. Now, until reading your book, I had been only vaguely familiar with the Volcker Fund. And what struck me was your description, quote, unlike most charitable foundations, people didn't come to Volcker looking for support.

libertarian views were so rare at the time that the fund had to actively search for thinkers worthy of its support. So we've certainly come a long way since then, as we were chatting before, here I am in Chicago going to foundations and looking for support. Talk about this tremendous growth since then and to what do you attribute its growth?

Yeah, one of the things the Volcker Fund did, it would pay people like Rose Wilder Lane, who was a friend and a little bit of an influence on Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard to like just read journals and read newspapers looking for people, academics, authors who seem to share libertarian ideas. And

By the time I started researching this stuff, a lot of the people involved with the Volcker Fund were dead. But I did get to spend a lot of time with a very interesting guy named Richard Cornell, who had been a program officer at the Volcker Fund. And he told me two different things that I think really illuminate the state of the libertarian movement in the 50s. He said sometimes they would find someone who, say, wrote an academic journal article that they thought, oh, this guy seems to have libertarian leanings. And they would approach him and the person would just, Cornell would say, like, they would be practically weeping

With the knowledge that, oh, my gosh, there are other people out here who believe this stuff, who think like me. I just didn't think there were any and just would be delighted to get connected with the Volcker Fund. And then you would find people who maybe had written something that seemed libertarian in one respect. But when you approach them and they would get the sense of like the larger libertarian world.

uh you know world from which Volker arose and they'd get angry they'd be like no no I don't believe all that stuff you know I might believe this one thing that fits with you but I don't I don't believe all that stuff you believe so both the joy and the anger at being kind of identified as libertarian I think says a lot about the state of libertarians and then and uh uh

Ironically, it's probably not the right word. Interestingly, it's probably the right word. One of the reasons why that has changed a lot is because the very work the Volcker Fund did. I'm going to talk about Milton Friedman here. He hasn't come up yet, but a very important figure, obviously. And in Chicago School Economist, look him up if you don't know him. He published a book in 1962 called Capitalism and Freedom. That was one of the major important books that actually they tried to bring together

the argument that the book's title indicates, that capitalism and freedom are intricately connected. Capitalism is an aspect of freedom. And he explained in great detail how the combination of those two things made for a richer, better world. And that book was formed mostly of lectures that Freeman gave in the 1950s under the auspices of the Volcker Fund.

The Volcker Fund was also the place where the entire intellectual field of law and economics was incubated. It's a little bit of a kind of an academic egg-heady interest. You don't see it as much in popular literature about libertarianism, but analyzing the law through an economic lens has had incredible effects on actual practice of antitrust law in America, actual utility law like

very specifically through Supreme Court decisions and judicial decisions, America is a freer place in many respects because of the field of law and economics, which was incubated at conferences and with funding from the Volcker Fund. The Volcker Fund helped keep Murray Rothbard alive. So everything that resulted from him, whether you love it or hate it, that's Volcker. So Volcker working in this

jungle, or this forest, whatever metaphor you want. The work they did helped change all that. They did what they intended to do incredibly well. It's an amazing history. So we're getting close to the end. We've got about 11 minutes left. Talk about the conservative-libertarian divide, how that manifested, say, in the 1950s, and how that's changed over time. Yeah.

in 50s 40s and 50s you'll pick this up if you read modern libertarianism the divisions i talked earlier about how this was really an anti-new deal coalition right and uh the divisions within that anti-new deal coalition were not quite as cleanly limbed as they became um you know william f buckley big new biography about him which i just reviewed at reason um

He started National Review in 1955, the flagship of conservatism. He felt he had a lot in common with libertarians. He was friends with Rothbard. He published Rothbard.

But the issue, and I think Leonard Reed a fee if you read his work and Rothbard too actually are the greatest exemplars of this. The conservative movement in the mid 50s were really powerful cold warriors, right? They're like, we hate communism. Well, yeah, libertarians hate communism too. But the conservatives, the Buckleyites thought that, well, the appropriate response to that was a government, even Buckley was actually comfortable using the word despotism. He's like,

We might need a native despotism. We might need nuclear war in order to defeat international communism. And that is stuff that the libertarians in that tradition, your Leonard Reed, your Rothbard's, your Baldy Harper's, you found in the IHS. They did not believe that, you know, they saw war, particularly nuclear war, like nuclear war was not something that could be fought in a way that libertarians could accept. It was necessarily mass murder of innocence and you couldn't countenance it. And the,

libertarians who saw themselves as libertarians were pretty solid on this point of course there's other things as well like you know vice laws and such but honestly when when you read the libertarian work in the 50s it's not that a libertarian would have supported vice laws but it wasn't like an issue that they really front and centered a lot like that's like

I mean, the drug laws existed in the 50s, but it wasn't a major public policy issue. So you weren't seeing like, oh, anti-drug war stuff, which became big in libertarianism in the 80s on. You didn't see a lot of that in the 50s. So you didn't see that distinction. But the war issue, the how do you combat communism, Reid and Rothbard would say, well, it's an ideological battle. Reid has a great quote, which is definitely in Radicals. It might be another libertarianism about it. It's like, we're fighting communism now.

through a war of ideas. We're not fighting communists. You know, we're not fighting them. We're not killing them for having these ideas. We're trying to convince them that they're wrong. So, and in a month, there are other issues have arisen since then. Abortion being one. Sorry, I have to plug my phone in. Abortion, you know, immigration now, weirdly, but immigration.

So you have in modern libertarianism a chapter on Atlas Shrugged and the objectivist movement now certainly at its heyday with the Nathaniel Brandon Institute and the books and the events, it was having an outsized impact. I have my own theories about why that impact has waned over time, but I'm curious to hear yours.

I'm probably going to punt to you. I will think out loud about this. Sometimes I just note historical trends, and I'm not sure I know the reason why. I would probably have said, well, there was a certain newness to random objectivism in the 50s and 60s, right? Atlas Shrugged came out in 57. She was like culturally hot in a way. And every few years that you, I'm sure, professionally have had to notice this, and I have had to notice.

Every like four or five years, there's a wave of stories in normal press about Iran's back, baby. And like, it's always a little bit true and a little bit not true. Of course, she never went away in a sense. But there was a sense of cultural heat about her that I think probably faded. But otherwise, I actually want to hear your answer, because I'm not sure that I have ever come up with an answer that I find convincing.

Well, I do think, of course, the split between Brandon and Rand and some of the deceit surrounding that in terms of not...

explaining some of the circumstances behind that was very disconcerting and confusing and really took the wind out of a lot of young objectivists at the time. I also think that this closed approach to objectivism, which is very judgmental and only sees this philosophy as

limited to what Rand said or wrote during her lifetime, when in fact Ayn Rand said a few years before she died, the elaboration of a complete philosophical system is a job that no philosopher can complete in his lifetime. There is still a great deal of work to be done. And I think that that kind of closed approach is one that psychologically, among other things, is

limiting, right? Because if you're protecting and preserving this kind of gospel, you don't have an orientation where you are going to take risks, right? And you are going to seek other alliances and opportunities to have dialogue. So, you know, our open approach to the philosophy and to the ideas, I think, has

is partly what's been responsible for the dramatic growth in the Atlas Society over the past few years. So that's one of my theories. All right, well, we have just a last few minutes. So I wanted to ask you, last week,

We had our third Galt-Skoltz student conference and also with the launch of Atlas Society International earlier this year and our 20 John Galt schools globally and our new European conference. It's pretty striking that

the momentum for growth of objectivism has in many ways shifted overseas. Do you think that's unique to objectivism or does it apply more broadly to the libertarian movement with great victories like that of Malay in Argentina and elsewhere?

Yeah.

in libertarianism internationally, I absolutely have come to understand that Latin America, I mean, Malay speaks for himself in a way. It's amazing that a guy with his beliefs, and in saying this, I'm not ratifying every single thing he's ever said or done, but that he won an election in a major country is brain-blastingly

wild for someone who grew up in libertarianism to see happen. Latin America, Europe, I even hear hints of Middle East and China. I think libertarianism as near as I can

almost doing better in a way, speaking places, but I can only speak to it as kind of an outside observer, not someone who actually understands the players or understands the dynamics, but I do understand it. Well, I can, as somebody who just does have some granular exposure to the key performance indicators, if you will, can certainly confirm that. We had an extremely long list for our international scholarships from

the student conference and had to really work pretty hard to get US students interested in attending. And also just with our digital content, let's say if one of our normal videos, our Draw My Life videos, for example, will get on average a million views in English, it will get 5 million views when we adapt it to Spanish.

It'll get 7 million views when we adapt it to Hindi. And by far,

the biggest audience size for our video content is Arabic and Middle East. So I think that there's probably a lot of preference falsification going on where you don't necessarily see these changes that are underway. But I think it is very encouraging. Now, balanced against all of that abroad, here at home, given the mega

movement and the MAGA moment and the upswing of populism at home and well actually abroad. Do you fear that young people will be lured into supporting more collectivist, illiberal policies? Yes, I do. I do think

In the American context, as I interact with it, I think that's definitely happening. I think, and you see it in many specific cases, like you can follow individuals if you've been, you know, whatever, Facebook friends or following certain people on Twitter from like the Ron Paul days to now, you see it happening. It's not happening universally, but definitely happening.

a kind of angry populism, a kind of populism a lot rooted in a real despising of what they associate with, like left-wing mores, you know, like the trad movement. It's like, you might've started as libertarian and then you get into like, well, I didn't like the sexual revolution. And I think,

you know, women should be having six children at home with a strong, rugged man who takes care of them. And like, that's a great way to live. And like, that's not a libertarian question. But sociologically, you definitely note that people who think that have a tendency to maybe start to see like they really think the mores and society has gone in a wrong way.

in ways that actually are connected with government in a way they're everything that happens in this culture is connected with government but it's not necessarily a question of oh this government policy

should happen or not happen, but they just are so mad at the way the world is that they're more willing to entertain. And we've got to do something about it. I think immigration is an issue like that. I do not believe there is a libertarian case for immigration enforcement, but a lot of people are just like, look, I don't like it. I don't like, I don't like the way this neighborhood looks. I don't like that I'm hearing Spanish everywhere, whatever it is they don't like. They're like, okay, I'm willing to see, you know, ICE agents throwing people into

Vans or whatever like I'm fine with that and they come up with an explanation that allows them to square being libertarian with it we're not going to settle that here, but I actually I

What I like about that phenomenon actually is that people seem so attached to the label libertarian. They like love thinking themselves as libertarian, that they're willing to do mental gymnastics to go like, I still want to be a libertarian, but I actually want to see people who haven't violated anyone's rights, you know, flown to a prison in El Salvador. And in a way that says something nice about the lure of libertarianism, but it's a bad thing, I think, that people who want to slot themselves in the libertarian movement are

are supporting all this Trump nonsense. And I think a great deal of it is just kind of

right-wing traditionalist perceptions about the outsider and the family that are overwhelming a dedication to what Leonard Reed called anything that's peaceful, which I think is the greatest way to sum up what libertarians are for or what libertarians will allow or tolerate, which is anything that's peaceful. Anything that's peaceful? Go on. Yes. I would say preferably, sure, it's great to say don't hurt people and don't take their stuff.

I guess what we objectivists try to bring to the table is like, okay, you're not going to take stuff. Are you gonna make stuff? You're not gonna hurt people. Are you gonna seek out other ways to provide value by being entrepreneurial? So it's the question of what are you going to do with your freedom? Again, Brian, thank you so much for joining us. Everyone, I highly recommend that you go out and buy Modern

libertarianism. And we look forward to Brian to your next, your next great book. So thanks. Thanks so much for joining us. Thank you very much for having me. It was a lot of fun. Appreciate it.

All right. And next week, everyone, I hope you will join us again. I will finally be back home after two weeks on the road. We're going to be talking with author Laura Delano about her book, Unshrunk, the story of psychiatric treatment resistance. We'll see you then.