Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

This episode is brought to you by Progressive Insurance. What if comparing car insurance rates was as easy as putting on your favorite podcast? With Progressive, it is. Just visit the Progressive website to quote with all the coverages you want. You'll see Progressive's direct rate, then their tool will provide options from other companies so you can compare. All you need to do is choose the rate and coverage you like. Quote today at Progressive.com to join the over 28 million drivers who trust Progressive.

Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and Affiliates. Comparison rates not available in all states or situations. Prices vary based on how you buy. Listener supported. WNYC Studios. You're listening to the On The Media Midweek Podcast. I'm Michael Loewinger. Happy New Year! For the first pod of 2024, I wanted to re-air one of my favorite stories that I've reported. I'm Michael Loewinger, and I'm going to be talking about the first pod of 2024.

In the fall of 2022, I was a witness in the federal criminal trial of Oath Keepers founder Stuart Rhodes, who was sentenced to 18 years for leading his group's siege on the Capitol.

I did an episode for the show called Seditious Conspiracy, in part about my reluctance to testify. I wanted to know how other journalists had navigated similar cases in the past, which is how I learned about the idea of immunity for journalists in federal court, and how I learned about the idea of immunity for journalists in federal court.

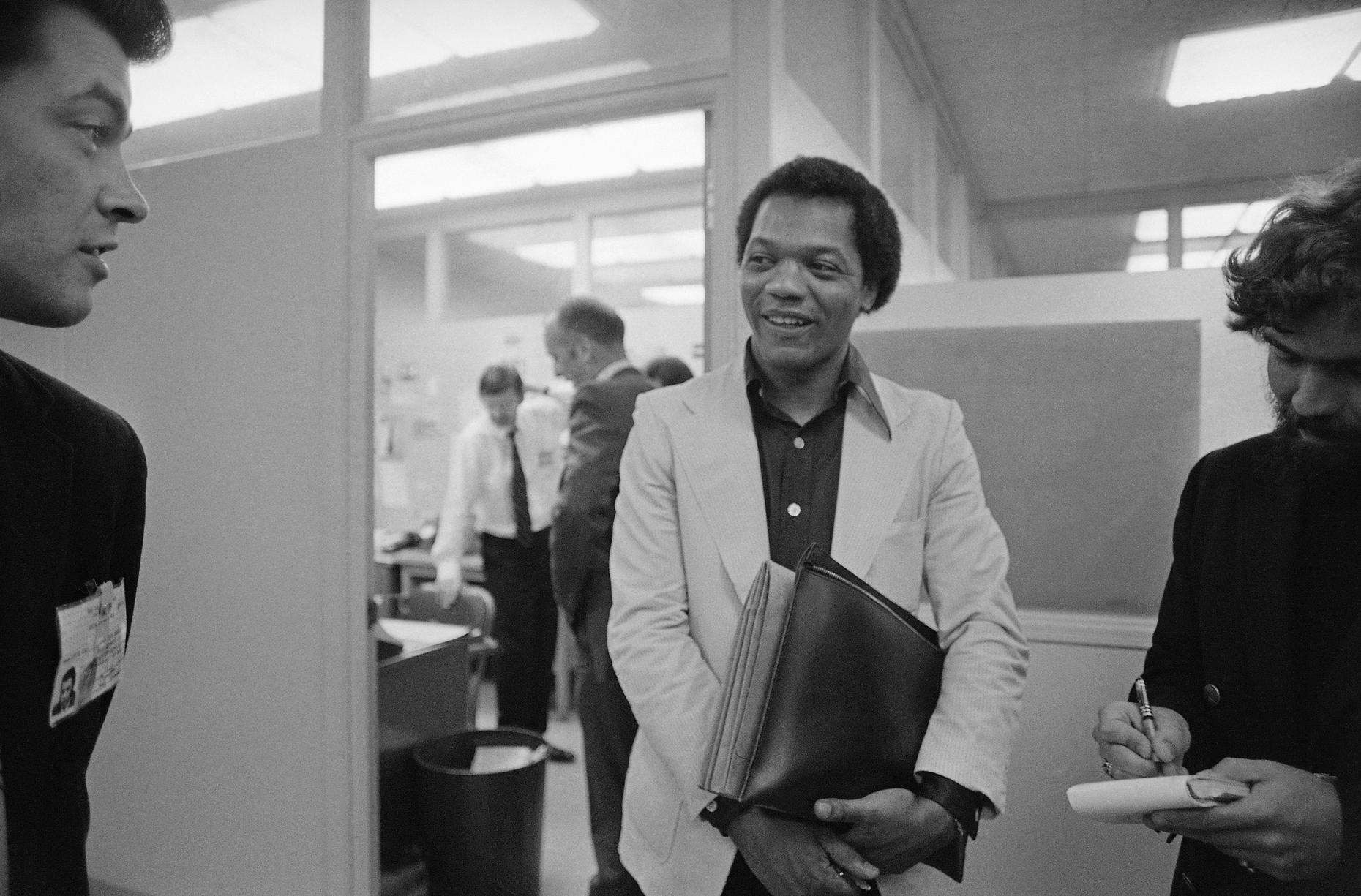

and the story of this man. We're interviewing Earl Caldwell this afternoon. I'll be inspiring Earl to speak on various issues connected with his career. This is a 2001 oral history done by the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education. Thank you very much to the Institute for giving me permission to use it extensively in this piece.

Earl and I spoke many, many times over the phone, but he never agreed to speak with me on the record. He's writing a book about his life, and he's stopped doing press. How long was that? It's two hours plus a few minutes. Whew.

Once I start to rub my mouth, it's all easy. The story begins when Earl Caldwell, then a reporter in his early 30s, joined the New York Times. There was only one other black reporter on the staff when I got there. And what was approaching was the summer of 67, which was to be like no other summer in the history of the republic.

The worst race riots since those two years ago in the Watts section of Los Angeles rocked New Jersey's largest city, Newark, for five consecutive days and nights. Law and order have broken down in Detroit, Michigan. Pillage, looting, murder, and arson have nothing to do with civil rights.

The paper flew Earl all around the country to cover the riots and the civil rights movement. And in April 1968, the Times sent him down to Memphis, Tennessee to interview Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Earl checked in at the Lorraine Motel, where Dr. King was also staying. And Dr. King gave me an interview. While we're sitting on the balcony talking, he...

begins to ask me about my personal life, how I got into the newspaper, what it was like being a reporter for the New York Times. He said, "We'll talk again tomorrow because we didn't have a chance to go through everything." And nobody told me there was going to be a big rally that night, which turned out to be a very historical moment for That's Where King Made His Mountaintop Speech. We've got some difficult days ahead, but it really doesn't matter with me now.

Because I've been to the mountaintop. Earl only learned about this speech later because he was back at the motel. And it was this fierce storm, like it was lightning and thunder. The shadows were rattling and everything. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the promised land.

The next morning, Earl heard about the morbid premonitions in King's speech. And the way Earl describes this day sounds like a bad dream. You know, that kind of dread when you're rushing somewhere...

but you feel like you're treading water. I'm trying to get to King right away, and I can't get to him, and the day is getting away from us, and I was missing my deadline. I imagine him pacing around his motel room, chain-smoking cigarettes, trying to figure out what to do when he heard a loud noise outside. I heard what I thought was a bomb blast, and I run out there in my shorts, and what happened? What happened? And then I ran up to the balcony, and I saw Dr. King. You could see he was

It's a horrible wound, huge, bigger than your fist and his jaw and neck. Dr. King was standing on the balcony of a second-floor hotel room tonight when, according to a companion, a shot was fired from across the street. In the friend's words, the bullet exploded in his face.

You can see Earl in some of the earliest photos of the assassination, in the scrum hovering over MLK on the balcony. He was the only reporter on the scene, and the first to break the story. So that was indeed the biggest story I ever had.

But it was actually the next big reporting project that's the focus of my story. The New York Times sent me out to California to look into this group that had been rising in California and was coming to some national prominence called the Black Panther Party. Within a matter of months,

Earl had developed deep access within the group. So it wasn't easy, even for a black reporter like Earl, to gain the trust of the Panthers. Lee Levine is a media law expert. He's writing a book about Earl Caldwell. The way he did it was providing what the Panthers considered to be fair coverage. You know, he was not misrepresenting who they were and what they were doing. I got so on the inside that I saw the Panthers...

moving a large cache of weapons from San Francisco to Oakland where Huey Newton, the leader in the Panthers, was on trial for murder of a police officer. 3,000 Black Panthers turned out for the start of the trial. Spokesmen say that if Newton is found guilty and given the death penalty, the sentence will have to be carried out over their dead bodies. I put this story in the paper, and when that story came out, the FBI came to the New York Times.

and demanded that I give them additional information about these weapons and how I knew it, where they were, all this stuff. And I said, you know, what I know about this, I put in the paper. And they're saying, well, look, you're there all the time. We want an inside report. We want you to tell us everything that you're getting, everything you know.

I said, not only could I not do it, I can't even have this conversation with you. They began to call every day. We now know that, in fact, the FBI had informants among reporters who they could plant stories with. There are multiple examples of what is called COINTELPRO, which is its counterintelligence program directed at a variety of what the FBI deemed to be subversive groups, which included the Panthers.

Forty years later, Earl was shocked to learn that his friend, Ernest Withers, a prominent civil rights photojournalist, had been an informant much of his career. So finally, one day, they called Mrs. Brackett. They said, you tell Earl Caldwell. We're not playing games with him.

And they got a subpoena for me to be the star witness against the Black Panthers before a federal grand jury. He had two strains running through his head. One was, as a journalist, I'm not going to be a snitch for the FBI. And then...

To make matters worse, the government also wanted his reporting materials, including the unpublished stuff.

And they were all in a storage room at the Times Bureau. Earl discussed his archive with a lawyer at a fancy San Francisco law firm that the Times had hired to deal with the subpoena. And the guy says to me, look, we have a tremendous problem with law and order out here.

And went on, according to Earl, to talk about the problem with black militant violence. The guy told him to bring in his notes and stuff so that he could go through them and told Earl that I think there's probably stuff that you have that the government is entitled to. And that totally freaked Earl out.

I'm sitting there thinking like, you're in an awful situation because you're at the top of your career. And all of a sudden they're saying something that could get you killed. It wasn't that somebody would say, go shoot Caldwell. It was that in this environment, somebody would say, if he came out here and told us he's a reporter and got on his axis and he's a spy for the FBI now, he shouldn't live.

Earl learned that the feds were going to come to the San Francisco Bureau to serve the subpoena. So we didn't know what to do and had all these documents. So we just said, we'll destroy it. Let's just shred everything. Let's dig these tapes apart, cut them up and everything. We had two of these real high garbage cans. We filled them up. And ultimately, he decided to fight the subpoena in court.

Hmm.

My feeling is that in reality, the reason the subpoena was issued was because Earl, among a few other reporters, was giving a view of the Panthers that was contrary to the government and specifically the FBI's preferred narrative to drive a wedge between Earl and the Panthers. They didn't need documents. They just needed to call him before a grand jury. And

have him testify behind closed doors, which is what happens in a grand jury. The Panthers wouldn't know what he said or if he said anything. Correct. Even if all he did in the grand jury room was assert his privilege not to answer substantive questions, I think the Panthers, justifiably, given what the FBI was up to, would have been...

nervous and would have cut off access to him. And actually, this became a big part of Anthony Amsterdam's defense for Earl. They rooted this idea of reporters' privilege in the First Amendment. Everybody understands that the First Amendment prohibits the government from preventing publication in advance. That's called a prior restraint. That's the Pentagon Papers. Everybody also understands that the government can't penalize you

after the fact for publishing information that relates to a matter of public concern, especially if it's true. What Earl was arguing is something different, but I think equally important, which is that even actions that government takes that don't directly prohibit or penalize the dissemination of information can have the effect

This is essentially what I was concerned about when I got my subpoena.

If people come to suspect that all reporters are just secretly working on behalf of the government, the social contract propping up journalism pretty much just falls apart. Do you want me to go on and talk about what happened next? What happened next was that the court was sympathetic to the argument but still ruled that Earl should go before a grand jury to authenticate his reporting.

The Times thought this was a fair ruling, and Earl was happy to say that what he'd written was true, just not behind closed doors. So Earl decided to appeal, and the Times, I think it's fair to say, was not happy about that.

Earl wanted to talk about appealing the decision. So he went to speak with the top in-house New York Times lawyer, Chief Counsel James Goodale. Goodale's shaking his finger at my face saying, you keep pushing this and what's going to happen is you're going to get some bad law written and reporters will be suffering for a lot of years under this. And I said, I'm not pushing anything. It's the Justice Department that's pushing it. But he tried to put it on me. This conversation turned out to be prescient.

At first, everything seemed to be going well for Earl and his legal team. Lo and behold, the Court of Appeals agreed with Earl and ruled that he didn't even have to appear before the grand jury. And this was a unanimous decision, right? Yes, unanimous decision. And so the government appeals. Yes, the government seeks review in the Supreme Court. And at the same time, there are these other cases wending their way around

through the courts. Paul Pappas, television reporter in Massachusetts, had also tried to fight a subpoena related to his reporting on the Black Panthers. Then there was Paul Bransberg, a reporter in Kentucky who refused to appear before a grand jury to discuss two sources he had witnessed making marijuana products. And all three of those cases were ultimately taken to the Supreme Court for review.

They were all rolled up into a single case known today as Brandsburg v. Hayes, since the case that comes up first alphabetically in the group often becomes the shorthand name. But United States v. Caldwell was considered the most significant of the three.

Earl thought that the mostly liberal court at that time would deliver them a 5-4 win. Unluckily for Earl and the other reporters, there was a dramatic change in the court's composition. The White House announced this evening that Justice Hugo L. Black, the oldest member of the Supreme Court, has retired from the bench. Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan turned in his resignation today just six days after the resignation of Justice Hugo Black.

allowing President Richard Nixon to appoint two new justices to the bench. The U.S. Supreme Court today took on the kind of conservative weight sought so long by Mr. Nixon. It did so by reaching its full complement of nine members with the swearing in of Justices Lewis Powell Jr. and William Rehnquist.

Justice Rehnquist came to the court from the Justice Department, and while in the Justice Department, one of his jobs as head of the Office of Legal Counsel was to formulate the administration's position with respect to this very issue. So... Everybody just assumed he would recuse himself, and he did. He was sitting right there. Why didn't he recuse himself? I don't know. I suppose he wanted to rule on the case and didn't think he had a conflict.

Just like today with uproars over Justice Thomas ruling on cases that some people think he shouldn't. There's really nothing that can be done about it. On June 29th, 1972, the court voted 5-4 against the reporters with Justice Rehnquist casting one of the deciding votes. Justice White, who wrote for the majority...

wrote that this whole concept of indirect restraints was bogus. And then Justice Powell, newly on the court, wrote an opinion concurring in Justice White's opinion, but adding a few words of his own. His opinion has been characterized over the years as enigmatic and

because it seems to suggest, although not entirely clearly, that there are circumstances in which, on a case-by-case basis, a reporter would be able to successfully refuse to answer questions posed by a grand jury. This enigmatic opinion by Justice Powell would turn out to have a long afterlife, which we'll get to in a minute. After the Supreme Court's decision, Earl never responded.

heard another word from the government. So he was never called to testify. There's an argument that the government accomplished what it wanted to accomplish, which is that it had established a precedent that would make sources in the future reluctant to talk to journalists.

But the Supreme Court said that, yes, the government can force you to be a spy and that if you resist, you go to jail. Here's Earl speaking with CBS in 1973. I honestly don't believe that it's possible to do effective journalism in America now.

Well, let me say this. In the immediate aftermath of the decision, there were, you know, the kinds of editorials you would expect in newspapers all over the country. Yeah, there was like a kind of a freak out. Yeah. Editors at the New York Times are worried about the effects of the Supreme Court's decision. National editor Gene Roberts says his staff reporters are already jittery. After the trial, Earle testified before Congress advocating for a federal shield law. Only when we can operate in an atmosphere free...

of the intimidation of government, can we assure the public that we are vigorously investigating all phases of corruption and political chicanery?

And lawmakers from both parties were listening. They discussed two kinds of bills, laws that would provide absolute immunity, no revealing of anonymous sources, no testifying before grand juries, period, or a qualified immunity, which would only require outing sources if three criteria are met.

One would be that the information sought from the reporter is relevant to an alleged crime. Second, that there's an overriding national interest involved. And third, and this is really the kicker in it, that it can be obtained, that information, from the reporter and no other source.

The issue is that news outlets were split on the question of qualified versus absolute immunity. They just couldn't agree. And as a result, the federal shield law died on the vine. The one constructive thing that came out of it was that Jim Goodale, the New York Times general counsel who allegedly wagged his finger at Earl, to his great and everlasting credit, decided that he should take Justice Powell's admittedly enigmatic language and pour meaning into it.

And over the next several decades, Jim kind of took the lead and was instrumental in having virtually every federal court of appeals and virtually every state Supreme Court hold that, in fact, there is the kind of qualified First Amendment-based reporter's privilege and that it operates in every kind of legal proceeding with the

In other words, Goodale and his fellow media lawyers successfully pointed to the Caldwell-Bransburg ruling to shield reporters from the judicial system. Despite this, several writers over the years have been forced to choose prison over revealing sources to a grand jury.

Judith Miller was jailed for 85 days. Vanessa Leggett was jailed for refusing to give up her materials to the government. Josh Wolf, the longest jailed journalist for protecting a source in U.S. history. Toward the end of my conversation with Lee Levine, he told me he was pretty sure I could have gotten out of participating in the January 6th case, that I could have fought the subpoena in court and won, which honestly came as a shock, and I think he could tell. Let me say this and it'll make you feel better. Ha ha!

Just a few years before this, during the first phase of the civil rights movement in the South, where reporters were witnessing the Klan engaging in violence and doing all other sorts of despicable things, many reporters were more than happy to share what they knew and saw and heard with the FBI. Nobody thought anything about it.

Thanks for listening to the Midweek Podcast. If you want On The Media in your inbox, subscribe to our newsletter at onthemedia.org. We have giveaways and other exclusive info that you don't want to miss out on. Also, be sure to follow OTM on threads. I'm Michael Olinger.