Can a Billionaire Be a Stoic? | Robert Rosenkranz (PT. 2)

The Daily Stoic

Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

Wondery Plus subscribers can listen to The Daily Stoic early and ad-free right now. Just join Wondery Plus in the Wondery app or on Apple Podcasts. We are hiring over at Daily Stoic.

And whenever we are hiring, the first place I go is LinkedIn Jobs. LinkedIn Jobs, it's super easy. They even have this new AI tool that will write your job description for you. You can put in the main stuff and it'll make it better for you. Your business is defined by the people that you have in it. And if you don't have good people, you're not going to do a good job. And so when you need a partner that works as hard as you do, that hiring partner is LinkedIn Jobs.

When you clock out, LinkedIn clocks in and LinkedIn makes it easy to post your job for free, share it with your network and get qualified candidates that you can manage all in one place. Posting your job is easy with LinkedIn's new feature and that can help you write job descriptions and then promote your job in front of the right people. Promoted jobs get more than three times the qualified applicants. And with LinkedIn, you can feel confident you're getting the best

That's why 72% of businesses using LinkedIn say that LinkedIn helps them find high quality candidates. Find out why more than two and a half million small businesses are using LinkedIn for hiring today. Find your next great hire on LinkedIn. Post your job for free at linkedin.com slash do it. That's linkedin.com slash do it. Post your job for free. Terms and conditions apply.

Mens sana in corpore sano, a strong mind in a strong body. I think we sometimes think of philosophy as this mental thing, which it is, but it's also a physical thing. The Stoics were active. I try to be active. You should try to be active. You've got to have a physical practice of

If you're looking for bigger muscles or just a bigger, better life, Anytime Fitness has everything you need to do that. If you want to get stronger mentally and physically, go to Anytime Fitness. You can get personalized training, nutrition, and a recovery plan, all customized to your body, your strength level, and your goals.

You'll get expert coaching to optimize your results anytime, anywhere in the gym and on the Anytime Fitness app. And you can get anytime access to their 5,500 gyms worldwide, all with the right equipment to level up your strength gains and your life. So get started at anytimefitness.com. That's anytimefitness.com.

Welcome to the weekend edition of The Daily Stoic. Each weekday, we bring you a meditation inspired by the ancient Stoics, something to help you live up to those four Stoic virtues of courage, justice, temperance, and wisdom.

And then here on the weekend, we take a deeper dive into those same topics. We interview Stoic philosophers. We explore at length how these Stoic ideas can be applied to our actual lives and the challenging issues of our time. Here on the weekend, when you have a little bit more space, when things have

Hey, it's Ryan. Welcome to another episode of the Daily Stoic Podcast.

Now, one of the criticisms I get for my work is that I make money from it. I've always found this criticism strange. First off, there's a lot of worse ways to make money than working really hard on a book and selling it to people. But, you know, a philosopher at a university is also compensated for their work. And I actually think that transaction in some ways is less

above board than maybe it seems like on first glance. Nobody's taken out undischargeable debt at 18 years old to pay for a copy of The Obstacle is the Way or The Daily Stoic, right? Nobody feels like their future depends on them having to do this. But if doing this doesn't help their

They actually don't end up getting a job from it. There's no recourse, right? I have no problem with the university system per se, but it is not a flawless system either. And then, you know, sometimes people go, well, what would Seneca think about this? And I go, I got to be honest, I don't give a shit what Seneca would think about how I make my living because Seneca lived on an estate tended by slaves and Seneca inherited an enormous fortune and Seneca made his money working for Nero.

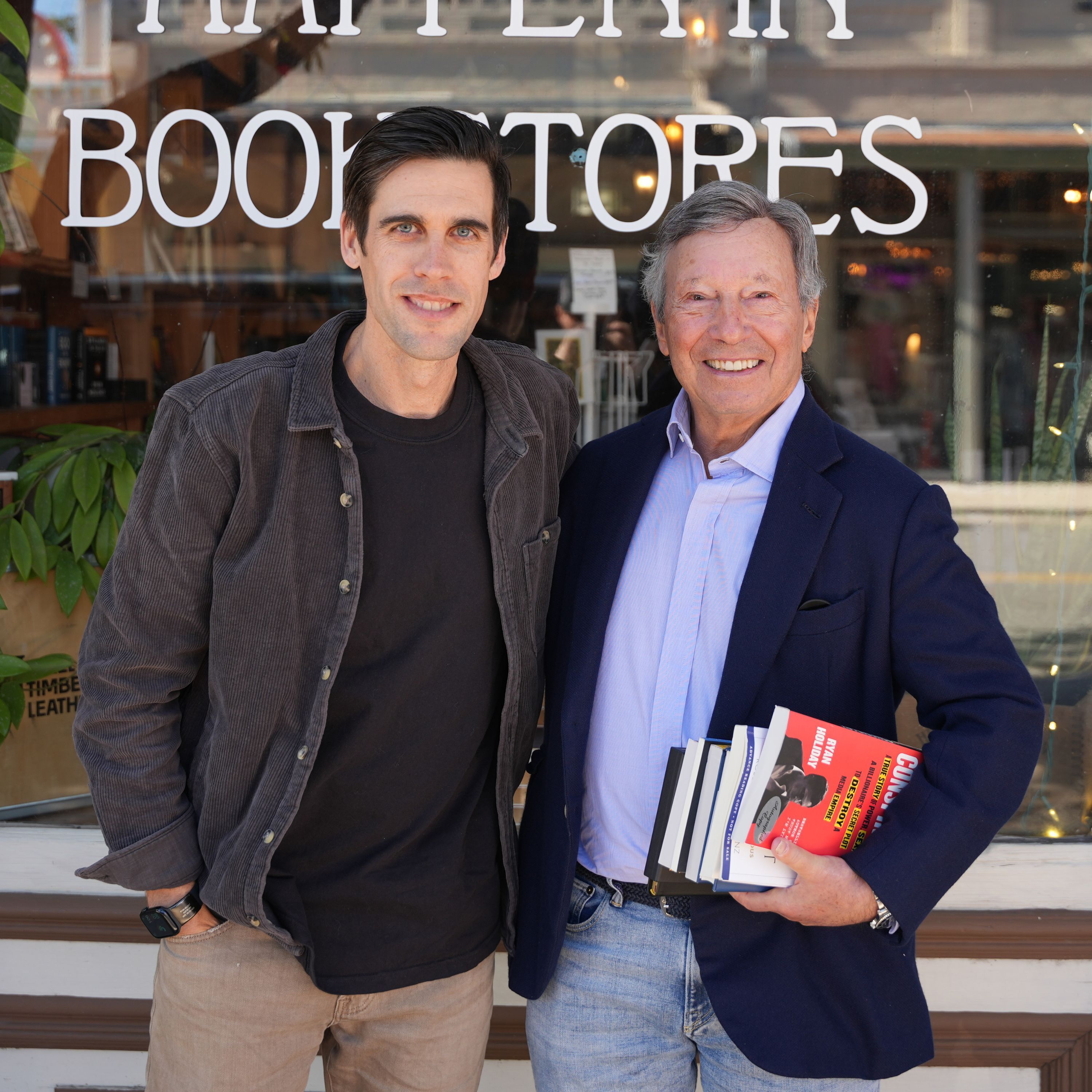

Right. And when I was talking to today's guest, Robert Rosenkranz, who is a hedge fund billionaire, a private equity billionaire and a student of Stoicism, he was pointing out that I am a capitalist. Right. Because I make things and sell them. And it's true. I was talking to my son the other day and he was asking about...

you know, like copyright. And I was explaining how we have a rental property and I was explaining how we own this thing. And when people want access to it, they rent it. Right. So I guess that makes me a capitalist in that sense. But I was like my books. Right. When somebody wanted to make a movie about one of my books, they had to

to purchase the rights to it because it's a piece of intellectual property. When someone wants to translate it in another language, intellectual property, the audio book for the Daily Stoic, the term is coming up and my publisher is going to have to bid on those rights again. Again, intellectual property. All writers are entrepreneurs. All creatives are entrepreneurs. The people whose podcasts you are listening to, the people whose YouTube videos you watch

These are capitalists by definition. Even if you might have views of what you do with your money later, you are still engaging in this system, the system that we have, the system that we have long always had. And by the way, Adam Smith studies stoicism as a college student and informs very much the work that he writes before The Wealth of Nations.

a theory of moral sentiments. So we've had some wealthy people on The Daily Stoic over the years, not just, you know, professional athletes and actors and business people, but we've had multiple billionaires on the podcast. I remember we had one guy on the podcast once and I sort of overheard him talking beforehand about...

about like an $80 million house he was buying. So that's obviously unfathomable wealth compared to what I have accumulated from the success of my books. But that is kind of a stoic point about wealth as well, that there's always someone that makes you feel poor.

and that if you are motivated by feeling rich, you're probably never going to get there, that that's not what it's about. But if you get good at creating value and you do it over a long enough period of time or you do it at scale, suddenly you can do quite well for yourself. One of the things that Seneca said was, you know, it's okay for a philosopher to be wealthy. There's nothing in philosophy that mandates you, you know, take a vow of

poverty and that you grind your way through life. He's saying what matters is that the money that you have isn't stained by blood. And I actually think that's kind of, you know, it's interesting that he says that because if there's any of the philosophers whose money was stained by blood, it was Seneca.

And that's a problem. And I guess I think about this with my eyes. I charge a fair price, I think, for my stuff. When we make stuff for Daily Stoic, we try to ethically manufacture it. We try to treat the vendors fairly. We try to be environmentally conscious, extravagantly.

I try to pay our employees fairly. I actually think about when we make stuff and we grow the business, like, am I employing more people? Am I helping other people realize their dreams? You know, and this is to say nothing of are we delivering things that people want? And if they don't want them, guess what? This is one of the nice parts about capitalism. People go, nobody needs a daily stoic coin. And I go, you're right. Nobody needs it. But some people want it.

And those people can freely purchase them if they like. That is the good part about capitalism, right? You don't have to participate in things you don't want to participate in. And if it turns out that I'm wrong, that nobody wants it at all, guess what? I'm the one that goes bust, right? It's my problem. I think of things that I like, that I'm interested in,

And I try to make them. And if it turns out that the people share that affinity, share that interest, or I'm good at making them interested in it, then it works out. But if it doesn't, you know, it doesn't. And that's on me. Maybe there's a little bit of the virtue of courage in there. They're taking risk and betting on yourself, trying to change the world of the market a little bit. So again, this whole topic, it goes way back in stoicism. I just find it, you know, so, so fascinating. This all, of course,

course, being relative. And that's actually kind of the subject of today's guest's book, The Stoic Capitalist, Advice for the Exceptionally Ambitious. This isn't like an academic just writing about what the Stoics would have thought philosophically about wealth or the philosophical implications of wealth. This is thinking about Stoicism and money from someone who has quite a great deal of it, who made it in the arena, so to speak.

And that's why I wanted to have Robert on the podcast. We did part one earlier and now this is part two. I really enjoyed this conversation. I think you will too. If you want to know more about what the Stokes can teach us about how to make money, kind of think about money, how to be wealthy in the true sense of the word. Well, I suggest you check out the wealthy stoic, our daily stoic guide to being rich, happy, and free, which is a.

sort of deep dive into the Stoic teachings on this topic. It is not about how to make money. It is how to think about money. If you want to check that out, I'll link to that. You can also join Daily Stoic Life and get this course and all of our courses for free. And then Robert's new book, The Stoic Capitalist is really good. And I think you'll like it. And I think you'll enjoy both parts of this conversation. Enjoy.

What is it like? I mean, I'm sure there's people listening who think I'm rich. I would look at someone like you and go, no, that's what rich is, right? It's always different. It's always more than what you have. No matter what you have, there's someone who has a bigger one. That's my other favorite thing is you talk to people or you read about it and you go, these people have all the money in the world and what are they waking up doing? They're calling reporters from Forbes to

to try to jockey for a different spot on this list, which is total bullshit. The whole list is made up basically. But that at that level, this I guess is what Seneca is talking about, having it is not enough. You have to have people know that you have it, or you have to be ranked as having the most. But anyways, I think people are probably curious about what it

feels like to have so much that you don't even have to think about it. Do you know what I mean? I've heard this phrase post-economic, where suddenly like anything you would think about is no longer a financial concern. Is it as magically freeing as people think it would be? Or do you still have the habits and mindsets that you picked up as a six-year-old with your parents not being able to pay the electric bill? Well, to me, the...

What was exciting to me about creating wealth was the process. The process was, in a way, joyful. The thrill of the chase? Well, it was the idea of being involved in a pursuit that used a very broad range of abilities. And I think this is incredibly important. And it's not just about money. It's about a well-lived life. If you find something to do in the world that...

engages all of your abilities, that encourages you to put all of your energy, that develops your full range of talents. That's, to me, essential to a well-lived life. And the business that I was in of doing leveraged buyouts...

did do that, did engage me in such a broad way and did make me feel that over time I was continuing to grow, continuing to learn. So it was really the process more than the, I mean, the money was great, but

The joy was really in the process and not in the money. I've tried to get there, to get to a place where I love writing books. And if you love writing books, published books come out of the other side of that. Like if you like the verb or the noun, which do you like better? I like doing the thing. And you know, Marcus Rios talks about this in meditations. He talks about

nature's inadvertence, these things that are sort of accidental byproducts. Like even meditations, he doesn't sit down to write a philosophy text that's going to survive for 2000 years. No, it's a self-help book, literally to help himself. Yeah. He's loving the process of kicking these things around, putting himself up for review, getting better. And the

The accidental byproduct of that is this work of lasting philosophical value. And I imagine there's part of that in building a business. You love all the decisions that go into it and finding the opportunities and setting up the culture and all. And then ideally the profits and the success and then the generational wealth is a

is an incidental byproduct of loving that process. - I mean, in your earlier question, you sort of asked me about, well, when you don't have to think about money, is that a sort of a liberating thing or what happened in that score? I actually tried consciously to do that really from a quite early age in the sense that my lifestyle was never a burden.

I'd much rather live a simpler life where I didn't have to think about personal living expenditures than live a grander life where I was always worried about, could I afford this? Could I afford that? Could I afford the other thing? And my parents who had to worry about paying electric bills, I didn't have to want to worry about paying anything. So I just lived beneath my means always. But

As my means expanded, that sort of beneath my means turned out to be a pretty luxurious lifestyle by most people's standards. Yeah. If your needs are small, that's a way to become prematurely wealthy, right? I guess you could say that. You know? And then as your success grows or your wealth grows or the funds you have access to improves...

Maybe there's a little bit of Epicureanism that we can, a dash of Epicureanism that we can add in there, which Seneca certainly does. It says, if you have it and you're not going to become addicted to it, or you don't think it says anything about your value as a person,

you can also enjoy it. Actually, there's a great line. You might like this. Okay, so Marcus Aurelius loves Antoninus. And what he says about Antoninus to me is maybe what we're trying to get towards. He says that you could say of him, as they say of Socrates, that he knew how to enjoy and abstain from things that most people find it hard to abstain from and all too easy to enjoy. He says...

That's great. You know, there's a little bit in the book about a Buddhist, one of Buddha's bodhisattvas who...

lived a very lavish lifestyle. And the other Buddhist disciples were critical of him and saying, what is this? You're living so lavishly. What kind of Buddhist are you? And his response was, no, you're just seeing the surface of things. And I'm a better Buddhist because I see the essence of things.

So it was really kind of interesting. He was also love debate. Yeah. So, so this would became one of my, my heroes. I mean, I get it as a talking point. I just don't, I don't find it that noble that Warren Buffett lives in a house he bought in the sixties. You know what I mean? Like, like good or bad. It just. Yeah. I agree with you. I mean, if, if your wealth enables you to live a richer and fuller life, I mean, I, I have beautiful homes and, but I,

I've enjoyed the process of creating them. I've enjoyed working with the architects. I've enjoyed the aesthetic judgments involved in them. I've enjoyed the ideas that are being expressed, which are almost philosophical ideas about

how to live well. And it's about creating environments that are contemplative, that are conducive to conversation, that are conducive to social events, that are conducive to listening to music or reading books.

Or just give you aesthetic pleasure and give your guests aesthetic pleasure, but in a thoughtful way. I mean, why not? Why forego that? Yeah, I mean, I guess one argument would be, well, you could give it all to someone right—you could give it all right now to people who have nothing, right? And I don't just mean to put this on you because it's true for all of us, like—

There are people starving in Africa. We all have extra. We could do things that are extra for us, but would be essential for them. What is the philosophical justification of driving a nicer car than you need to or having a vacation house or, you know, adding in a big addition to your house?

I think philosophically, I sometimes wrestle with that. How do you think about it? Well, I mean, I think it's a classic kind of philosophical divide between Rawls and Nozick. So Rawls writes about distributive justice.

And what is the fair allocation of stuff? Yeah. And he sees the government's role as embodying some notion of fairness and redistributing wealth in accordance with that notion. Nozick felt like, no, that's the wrong question. It's what is the fair process of acquiring wealth?

goods or claims to services. And if the process is fair, i.e. it doesn't involve force, it doesn't involve coercion, it doesn't involve dishonesty, it's just a result of free exchanges between free people making rational decisions, that's all you should ask. If the process is fair, you don't meddle with the result.

I don't know anyone whose inbox isn't a huge mess, who managing email isn't a day-to-day struggle. I'm looking at my email right now. How many unread emails do I have? I've got here 298 in my main email, and I've got

147,000 in my other email. That is insane. And that's where today's sponsor comes in. Notion Mail is the inbox that thinks like you, automated, personalized, and flexible to finally work the way you work. And with AI that learns what matters to you, it can organize your inbox, label messages, draft replies, and even schedule meetings. No manual sorting required.

Plus, if you're a Notion user already, which we are here at Daily Stoic, Notion Mail integrates into your account and uses your Notion docs for context as well. It's just a great service. You can get Notion Mail for free right now at notion.com slash TDS. And you should try the inbox that thinks like you. That's all lowercase letters. Notion.com slash TDS to get Notion Mail for free right now. And when you use our link, you're supporting the show. That's notion.com slash TDS.

May is Mental Health Awareness Month and Talkspace, the leading provider of online therapy, helps you face whatever is holding you back with a caring, licensed therapist. With Talkspace, you're not alone. One in five adults in the U.S. experience a mental health condition each year.

but less than half of the people who need treatment receive it. And it's the Talkspace mission to help close that gap by making high quality therapy and psychiatry more convenient, fast and affordable. Talkspace is super simple to get started. You sign up online, you can get paired with a licensed provider within 48 hours.

and you can take your appointments from the comfort and privacy of your own home. You can even text or send video messages to your therapist. Plus, most insured members have a $0 copay. Take care of yourself this month and every month with Talkspace. Talkspace is in-network with most major insurance plans.

But if you pay out of pocket as a listener of this podcast, you'll get 80 bucks off your first month when you go to Talkspace.com slash stoic and enter promo code space 80. That's space 80. To match with a licensed therapist today, go to Talkspace.com slash stoic and use promo code space 80. Well, Seneca said, you know, it's fine for a philosopher to be rich provided that his money is not stained in blood.

And what's interesting about Seneca is you could argue that he fails that test, right? That, I mean, he gets a good chunk of his money from a murderous, deranged dictator that plenty of the other Stoics resisted. But I think there's probably something in the middle of the two of those, right? Because the process can only be fair and just...

in a functioning society or a rules-based order, right? Like you can't be a billionaire from certain foreign regimes and say, oh, well, I got mine through a fair process because your country is fundamentally unfair, right? Like the game was rigged. You may have played the game fair, but the game itself was rigged or exploitative or unjust. But yeah, I think that makes sense. It's just...

There is something, I think, this sort of stoic principle of justice where, yeah, you can go, hey, I got this in a fair way, but I am chasing a 1% increase in my personal pleasure.

that would have a transformative impact on someone else, which I guess is where the idea of needing to be generous also comes in. That, you know, as they say, if you've been blessed, be a blessing. To me, that's obviously a biblical idea, but I think the best Stoics illustrate that also. How do you think about, you have an interesting section in the book where you talk about someone who basically came into your office to fuck you over and

You were naturally quite angry about this, but you make a distinction, which I think is an important one. And the Stoics certainly make to the distinction between getting angry and doing something out of anger or getting angry and acting angrily. Well, you're practically paraphrasing one of the chapters, which is you can get angry, but don't act angry. And I think that's a sort of a general Stoic principle that

I think is vital in almost any pursuit, which is that your emotional response is automatic. But how you act on that emotional response should be a conscious choice and you should take responsibility for it. And the particular story that you're telling or referring to, this bank, which was one of the larger banks in New York at the time and had been a lender to deals that I had initiated,

had a dodgy loan and they wanted me to take it off their hands. And I owned a substantial insurance company with a portfolio so I could buy the loan in the insurance company. And they said, look, if this gets into trouble, we'll buy it back from you. And I knew that they couldn't put that in writing because of regulatory considerations, but the loan then did get into trouble.

And they wouldn't buy it back. And they had excuses. And then they needed my consent to a general arrangement called extend and pretend, where they were going to not make the borrower pay off, but hope that he would sometime in the future. And I said, no, I'm not going to go along with that. And the president of the bank comes into my office. And he was a very impressive figure.

And he basically said, look, you may be legally right in doing what you want to do here, but if you persist in this, it's going to be very damaging for your reputation, not only with our bank, but with the other banks in the syndicate.

And I felt this guy was a bully, that he was pushing me around, that I had done a favor for him. And now he was screwing me over. And I was really genuinely angry. But I hit the pause button. I went to the men's room and I realized I've got to capitulate. And if I'm going to capitulate, it's in my self-interest to do it with as much...

graciousness as I could muster. So I did. And I thanked him for coming to my office and thanked him for explaining why this was so important to the bank and to my reputation and fine. And then comes the stoic part of the story, which is that I had the impression of him as a bully. But after this transaction, he said,

Bob, if you ever need a favor from this bank, come directly to me. So, you know, the exact opposite of a bully. I mean, a gracious guy, gracious. I was trying to be gracious in defeat, but he was equally gracious in victory. So I love that story, actually. Sometimes in business and life, you just have to accept that you're going to get fucked. That's just a

A thing that I think people who are successful and driven have an especially hard time with. Because you go, I didn't get here. I didn't get where I got by accepting things or letting people push me around. But even Marcus Aurelius had to swallow stuff he didn't like and had to accept people behaving in ways that he didn't like. But Spinoza says this too. He says that...

It's simply human nature to use your power to protect what you consider to be your vital interests. And so this bank or the head of this bank was acting the way he should act, using his power to protect the vital interests of his bank. And the lesson from that is not

"Oh my God, capitalism is a vicious system," or "Banks abuse their power." But this is just part of human nature. And if people don't act the way you think they should act, maybe the problem is not what they're doing, but the problem is in your expectations. We use that word "act," which I think is interesting because one of Epictetus's metaphors is that we're all actors in a play. We've all been assigned different roles.

And our job is to act those roles well. And I think that's helpful not just to go, hey, you know, I was born tall or I was born short. I was born in this country or that country. I was born in this era or that era. To understand sort of where we are and some of the ceilings, limitations, you know, factors that are acting on what we have or don't have. I think it's really helpful. But I've also found that metaphor from the Stokes to be very helpful in understanding other people. Like,

Is a play without villains possible? Is a play without comic relief possible? You know, like I try to go, this person is doing their job. Like I hate them. I hate their job. Their job sucks. I'm glad I'm not that person. And I don't like that I'm on the receiving end of their things. But like the director wrote the play this way.

And I don't mean that in a, like a religious sense. I just mean like, what did you think you could make it, you know, decades in finance and not meet, you know, an asshole who throws their weight around? Of course, you know, like we sometimes think that everyone is going to be the good guy and that's not how plays and tragedies and.

entertainment works. Like everyone has a role. The person in front of you in traffic is playing the role of the slow person in traffic. But I think there's, to me, an issue or the way Epictetus writes about it, he's coming from a place in a society where there was really very little mobility. No agency. You were really in the place where you were born more or less and that was it.

And I feel like I'm incredibly lucky to have been born in America, which valued as much as anything the idea that people of ability, regardless of their circumstances at birth, could get a great education, could build a business or a fortune, could aspire to a position of power.

and or respect in the society. And that's in part why I may have come to Stoicism late, because it's not about ambition, or at least Stoicism doesn't write a lot about ambition, because people are coming from a place where you were pretty much born into a role. And I think if this book has an original contribution to make, it's really applying these ideas to a world in which

ambition is possible and is reward. Yeah, look, dynamism and agency and meritocracy, these are

These are inventions that come after the Stoics. And I mean, there are things we're still struggling with today. I mean, we have a society with a lot more agency and dynamism than the Greeks or Romans did. But hopefully the future will have even more, right? Like hopefully we're things that, I mean, certainly in your lifetime, things have gotten fairer. People have gotten, opportunity has been equalized in a way that it

Different races and genders and religions have more seats at the table than they did before. That's all great. And so, yeah, the Stoics didn't understand certain things. And also the idea that you don't have to have a feudal slave society. That's an invention that comes after the Stoics. The idea that there are ways to resolve problems other than violence is an invention that comes after the Stoics.

the idea that one country can't just steal the sovereign territory of another and turn them into a vassal state. This is an invention. And I think the Stoics, if you picked up and dropped Epictetus and Mark Strelitz and Seneca in today's world, they would get with that program really quickly, but they just didn't fully have access to it. And that's the really powerful thing about paradigms. Like Epictetus didn't

even though he's a slave, doesn't seem to question the right or wrongness of the institution of slavery. And maybe that's a flaw in Stoicism, that it's a little bit too much about acceptance and not enough about human agency. I agree. I mean, that's, I wouldn't say it's a flaw about Stoicism, but it's, the Stoics came from a society that simply didn't have

those same opportunities. And I think those ideas can play out in a different kind of society that does value meritocracy, that does provide these avenues for, uh,

for people to realize childhood dreams where those dreams might be a million miles away from where they started. - Yeah, some of these things aren't possible until someone shows us they're possible, which to its credit, Mark Struis talks about in "Meditations." He says, "Know that if it is humanly possible, you can do it also."

And it's not until you get these. I'm actually a big believer in the great man of history theory. I think history was shaped by individuals who did things that people didn't think were possible. Some of those were monsters, Hitler, and then some of them were Gandhi who show us, you know, hey, this is a better way to do that.

And the Stoics obviously could only conceive of the things that they could conceive of and the things that were possible. And we have another 2,000 years of history of creators and activists and thinkers and philosophers and scientists who showed us that different things are possible. And hopefully, I think one of the things we take of is that although there are still

the things that are in our control and the things that are outside of our control, and a lot of those fundamentally don't change, other people, the weather, et cetera, more things are in our control. Death is still a fundamental reality, but we've learned, hey, if you don't drink water out of lead pipes, you know, you'll live longer. You're absolutely right. And, you know, that distinction between what's within your control and what's not is

It's not a black line. It's not a big sign telling you. So I find, and I believe that it's better to give yourself the benefit of the doubt that if you try to change something that's important to you and fail, at least you've had an opportunity to learn something. Whereas if you don't try at all, you're nowhere. Yeah. Just because you believe you can do something doesn't mean you can.

But if you don't believe you can do something, it almost certainly will not be done by you. Exactly. There's a line, another line from Marcus Aurelius that reminds me of a rule you have that I thought you might be able to explain. You had this investing rule. But Marcus says that what he learns from his philosophy teacher is to read attentively and not be satisfied with just getting the gist of it. Exactly. You say we should always read the footnotes.

Tell me about this. Okay. Well, this is in a chapter dealing with investing and investing is weird.

It's one of the, the SEC makes you put on the prospectus that past performance is not an indicator of future performance or doesn't predict future results. And the SEC is right, but it's kind of weird. I mean, if you're a good violinist today, you're probably going to be good tomorrow. If you're a good heart surgeon, you're going to be good tomorrow. If you're almost every other human pursuit is,

The past does predict the future. So why in investing does that not pan out? And I write about a number of different reasons. One is that some good results are based on luck. One is that some good results are based on running a small amount of money and that it doesn't translate. So if past performance is not a good guide, what can help you?

And it's really thinking very critically about the manager, the strategy.

And reading the footnotes is simply a way of, I mean, the manager will have, you'll look at a track record and then you'll read a pitch deck, which is the things the manager wants you to know. But the things he doesn't want you to know are usually in the financial statements and even beyond that in the footnotes. So he doesn't necessarily want you to know how much he's borrowed in order to achieve his results. He doesn't want you to know that he's taking his own money out.

He doesn't want you to know that there's maybe some self-dealing transactions between the fund and a brokerage operation. Maybe the past performance only looks like good past performance, but it actually wasn't. Well, that's another thing. Maybe what the footnotes will tell you is...

The performance is a result of marks. So these are securities that maybe don't have an active public market. It's private capital, private equity or private debt.

And the manager, because there is no active public market, the manager has sort of set the marks. And if you read the footnotes, you'll know that. And then it can give you some skepticism about, well, the whole track record is based on that he says that what he bought at $1 is now worth $2.

It doesn't matter what Zillow says my house is worth. It matters what someone will buy it for. Like the valuations are bogus. Yeah, exactly. The gist of it would be, hey, I like this guy. The numbers look pretty good. He comes highly recommended, man or woman.

And reading the footnotes says like, no, I'm actually going to see if this is true or not. Is that the idea? Well, yeah. I mean, that's certainly one of the elements of diligence in picking managers. But I think, again, there's quite a bit in the book on individual what makes a good investment strategy.

Stock picking is a bad strategy, and I explain why. But a good strategy might be operating in a little niche that people don't understand very well and there's not very much competition. Right. Or something that's asymmetrical where, you know, you have just people in the marketplace who –

either don't have information or who are forced to act in irrational ways. Maybe they're forced to sell, let's say, take example of bonds that have been downgraded or in default.

Well, most institutional investors, insurance companies, banks, regulated enterprises like that are forced to sell by regulators or forced to sell by rating agencies. So you have asymmetry. Well, that can create a very good strategy. So a debt might have been, they might not be able to possess something that you looking at find attractive.

to be safer than their black and white rule is allowing them to- Yeah, or they may be unable to make a judgment. I mean, look, every security is a good buy at a price. Yes. So they may know that at 50 cents on the dollar, this is a pretty good bet.

But they can't hold it at 50 cents on the dollar. They can't hold it at all. So if the best they can get is 30 cents on the dollar, 20, they've got to sell. And that's kind of asymmetric behavior and a strategy that would give, you know, that in my mind would be an attractive strategy. Right. And then the gist is it's bad.

In that case, just zooming in on that, the gist, to extend this metaphor, the gist is their rules tell them, I can't hold this. It's bad, not valuable, whatever. And you really looking at it go, actually, hey, no, at a certain price, it is a good investment. And I'm not beholden by the same rules or constraints as you are. So by having read the footnotes, done the work, actually, this thing is great. Yeah, exactly so. And when you find a strategy that has that

Asymmetry, that's an interesting place to look as an investor. It's easier to just get the gist of things. It takes more time to do your due diligence and to read the footnotes and to question your own assumptions, doesn't it? Well, of course it takes time and it takes engagement and it takes presence of mind to do that. But if you're going to succeed in any pursuit in life, you ought to be a student. You ought to be mindful. You ought to be thoughtful about what the hell you're doing.

It's one of the best times of year here in Texas. Spring is amazing in Austin, but you just sort of know deep down it's about to get really hot.

A big part of our lives in the Texas summers is staying hydrated. And that's where today's sponsor Liquid IV comes in. Liquid IV is clinically studied to maintain hydration better than water alone for up to four hours. Visit liquidiv.com and live more with sugar-free hydration and you'll get 20% off your first dose.

order with code daily stoic at checkout comes in a little pouch you mix it with water we throw them in our backpacks or we've got a couple in the car we have some at the office

When you're spending a lot of time outside or you're traveling, you know, it's just a great way to avoid that dried out feeling, that grouchiness, that fatigue that comes from being dehydrated. Maximize your hydration with Liquid IV and get 20% off your first order of Liquid IV when you go to liquidiv.com and use promo code DAILYSTOIC at checkout. That's 20% off your first order with code DAILYSTOIC at liquidiv.com.

Ryan Reynolds here from Mint Mobile with a message for everyone paying big wireless way too much. Please, for the love of everything good in this world, stop. With Mint, you can get premium wireless for just $15 a month. Of course, if you enjoy overpaying, no judgments, but that's weird. Okay, one judgment. Anyway, give it a try at mintmobile.com slash switch. Upfront payment of $45 for three-month plan, equivalent to $15 per month required. Intro rate first three months only, then full price plan options available. Taxes and fees extra. See full terms at mintmobile.com.

So Seneca said if you put all the wisest people in a room, they would struggle to wrap their heads around the fact that we value property and money more than time. That time is the most precious resource, but we don't treat it as such. Even very wealthy people don't treat it as such. Why is this? Well, because we're not all Stoics. I've done things in my own life to try to very consciously maximize time, but

Like what? Well, I do a, every once in a while, I'll take a yellow pad day, what I call, I'll go to a rare book library or someplace where I'm not going to be disturbed. I'll turn off my phone and I'll think about, okay, let's think about the people in my life. What relationships may have outlived their usefulness? What relationships might need repair?

Who are some people that I'd like to really spend more time with? Who are people that I'm spending time with that I'd like to spend less time? Be really conscious about that. Have I fallen into bad habits? Am I spending my time in ways that are unproductive? Are there opportunities that I should be seizing? Are there risks that I should be thinking about?

Are there changes in the world that, you know, will create either risks or opportunities that I haven't thought of? And by spending a full day like that, I come away with a much clearer sense of how I should be allocating my time. Marcus Aurelius has a great train of thought that for peace of mind, do less. Yeah. But do it with greater concentration. Yeah. Yeah.

And I really take that lesson to heart. My house sits next to an empty lot or we thought it was going to be an empty lot forever. And then someone bought it and was building a house on it. And when they cleared the property, they cleared a bunch of trees that were technically on my property.

And I said, hey, you know, you cleared these trees on my property. You got to work something out here, you know? And he said, oh, I'll take care of it. I'll plan something new on your side. Don't worry. I said, okay. And then, you know, they were parking trucks on my front lawn and messing stuff up and it's going on. And I finally got to a place where I was like, you know, you can't keep doing this.

And then he showed himself to be one of those people. These people exist in life who decide to not just be to do something that negatively affects someone else, but then to be a jerk about it. And I remember going, okay, I could sue this person. I could argue with this person. I could fight with this person. I could be upset about this injustice that's been done to me. But in the big scheme of things, it's not enormous.

And what am I going to recoup here? And then I thought, I have money, so I can easily just fix this problem. I thought of what Seneca talked about, which is we'll be so mad if someone builds on our property, right? If they cross the property line, we'll get very upset.

but we'll let someone steal our time. And what I was going to do is I was going to allow this person who already stole or damaged my property, I was going to allow them to steal my time on top of this.

And I thought, you know what, this is what money is for. And I just paid to fix it. And I don't, we don't talk to this person and they can go on being themselves. But to me, there's a really important stoic lesson of, you know, they say you're throwing good money after bad. Often what we do is throw time after money or after a mistake or after a negative experience that actually ends up costing us far more than whatever the original experience

Yeah. I mean, you're absolutely right. And, you know, you feel like your neighbor has treated you unjustly. Yeah. And you're angry. But then the question is, what do I do about that anger? Do I spend a lot of time...

trying to write this wrong? Or do I say, you know, in the grand scheme of things, this doesn't matter very much. I'll just write a check. Now, one of the advantages of wealth is that maybe you resolve this dilemma in a different way. Like I have a house in Aspen and next to me was another property that came on the market for sale.

And it was the ugliest house in Aspen. And I knew whoever bought it was going to tear it down. And I was going to have a construction site next door. So I bought it myself. Sure. I tore it down myself. I built something that I loved, which was an art barn. And I loved the process of building it.

So, you know, wealth does give you the ability from time to time to to convert what might have been an irritant into what might have been an opportunity for creativity. Yeah, no, I totally agree. And I would say, like, look, if he's abusing children in his basement or he's stealing taxpayer money, there's another part of me that goes, hey, this is an important thing that I need to fight for the principle of where I need to get justice for. Right.

But in this case, it's like a tree or whatever. You know, like we can sometimes get caught up in needing to be right. And like in your story, you could be right or you could just pay to make the thing go away, right? Yeah, and that's your story. Yes, yes. That's your story. And you absolutely, I think, came to the right stoic conclusion. Yeah, it's like, are you going to try to impose your will on this person or win the argument? Or are you going to preserve the most valuable thing that you have?

which is your time and also your sanity and happiness. So like, let's say my time's not valuable, but this is the thing that Stokes talk a lot about. If in getting revenge or getting your justice, you're stressed, you're angry, you're,

I'm short with my children. You know, I'm spending all day at the courthouse or whatever. I'm not just costing myself time. I'm becoming worse as a result of this victory. And so it's kind of a Pyrrhic victory that we often end up winning. Yeah, that's fair comment too. I mean, if you're angry and you're coming home and you're feeling

you know, the sense of grievance and injustice. I mean, not only it's hard to take care of your children, it's hard to take care of your own health. It's hard to make decisions that serve your interests well. It's a vicious circle. All right. So last question. I saw this interview with the founder of Kinko's once, and someone asked him like what his definition of rich was. And he said, look, there's lots of people that have lots of stuff.

He said, but being rich is having kids who want to come home for Christmas. I'm just curious, when you have, by any means, people would say is an enormous fortune, what do you find as a parent, as a human being, you ultimately end up valuing the most? I mean, ultimately, it's at least in terms of children, parents,

I wanted my children to have possibilities in life that I didn't feel I had. I wanted them to be able to be scholars if they wanted or public servants if they wanted or do... I wanted them to be able to live a productive life in whatever pursuit without feeling this constraint that I felt of trying to establish financial security. So that seemed very important to me.

But it also seemed important to me to put your relationship with grown children in this sort of category of things that you really can't control. You know, maybe you have some control over your kids when they're young. And even that, a lot of it is genetic accident. Yeah.

But I think there's an acceptance or there should be an acceptance of the idea that these are adults and they are who they are and you don't have much control over it. If it works out in a way that you have a warm, nice relationship with them, that's great.

But if it doesn't work out that way, maybe that's something that you should accept with stoic detachment. Yeah, someone was, I posted that video one time on Daily Dad and someone responded, actually, if you're rich, you should go visit your kids for the holidays. Don't make them come to you, which I thought was an interesting lens at looking at the situation too. But yeah, I mean, I think our job is to help our kids become who they want to be, not

what we want them to be. Exactly. But that can be hard when you're used to getting your way, I imagine. Not you specifically, but like for people who are masters of their universe, the powerlessness that you have over your children, rightfully in the sense that it's their lives and they're going to do what they want with them, that can be a difficult thing for people to accept.

You know, I must say, for me, it wasn't. I felt philosophically... First of all, I was very analytic as a parent. So I had read these twin studies where twins from radically different environments turned out to have almost identical educations and looked the same and married women who looked the same. And then in reading all these biographies...

I mean, it was all different kinds of parenting. I mean, a lot of people were brought up by servants and really had no real involvement with their parents. Other people, you know, had brothers or sisters or siblings who didn't amount to much from the same environment, same parenting. So I just...

sort of intellectually had this idea that parenting had only limited influence and that kids were going to have to learn for themselves success felt better than failure. And if you cared more about your kid's success than they do, you're setting yourself up for sort of an emotional blackmail. And in my case, I was rebelling against my parents, but I was rebelling against their bad ideas and their failures.

I didn't want my kids to rebel against success. So I wanted them to sort of develop a sense of ambition from their own experience. I want them to live in the fact that succeeding feels better than failing. Yeah. Give them room to fail. But also when you begin to have a reputation and a platform and, you know, it can be hard to...

to not see your kids as a reflection of you. I think that's a very tempting thing. I remember I was reading an article about that college admissions scandal and they have one of the, you know, billionaire investor, whatever parents on,

on the wiretaps and he goes, "I just, I can't have a son who goes to Arizona." You know, like he couldn't have a kid go to University of Arizona because all of his friends' kids were going to Harvard and Yale, you know? And so the idea that your kid's choice of college says something about you is such a narcissistic and toxic thing to foist on them. - Yeah, I mean, that goes back to what we were talking about about self-esteem. If your self-esteem comes from the opinion of others,

you're in pretty shaky ground. Yeah. Yeah. And it's going to set up a lot, like it'll go great if your kids agree and want to go to the school that you want them to go to. And, you know, whatever, I hope the dice roll that way for you. But the chances of that happening are slim. So, or it's setting you up for a lot of conflict, right? And so-

to get in a place where you want your kids to be who they want to be. That's the recipe. Like Epictetus talks about how if you want to be happy, you wish for things to be as they are. I don't think he means that so much passively. I think he means it for scenarios like this. Like if you want your kid to be a certain way,

that's setting you up for potentially a lot of unhappiness. If you want your kid to be what your kid is and you want them to do what they want to do and pursue what they want to pursue in life, now you're much more aligned. And the chances of that being a good relationship, I think, are higher. I agree. Absolutely. I love it. Well, I thought the book was really interesting and I'm so glad we got to talk. Well, so am I. This was really great.

Thanks so much for listening. If you could rate this podcast and leave a review on iTunes, that would mean so much to us and it would really help the show. We appreciate it. And I'll see you next episode.

If you like The Daily Stoic and thanks for listening, you can listen early and ad-free right now by joining Wondery Plus in the Wondery app or on Apple Podcasts. Prime members can listen ad-free on Amazon Music. And before you go, would you tell us about yourself by filling out a short survey on wondery.com slash survey.

Whole Foods started in the counterculture city of Austin, Texas, and it took pride in being anti-corporate and outside the mainstream. But like the city itself, Whole Foods has morphed over the years, for better and perhaps for worse, and is now a multi-billion dollar brand. In the latest season of Business Wars, we explore the meteoric rise of the Whole Foods brand. On its surface, it's a story of how an idealistic founder made good on his dream of changing American food culture.

But it's also a case study in the conflict between ambition and idealism, how lofty goals can wilt under the harsh light of financial realities, and what gets lost on the way to the top. Follow Business Wars on the Wondery app or wherever you get your podcasts. You can binge Business Wars, The Whole Foods Rebellion, early and ad-free right now on Wondery+.